Validation of “Care of the Dying Evaluation” in Emergency Medicine (CODE-EM): pilot phase of end-of-life management protocol offered within emergency room (EMPOWER) study

Introduction

Globally, the population is ageing, with the number of persons aged 80 years and above projected to rise to 425 million by 2050, a three-fold increase from 2017 (1). Consequently, an increase in chronic illnesses and comorbidities is prevalent among patients presenting to the emergency departments (EDs), rendering the care of such patients to be more complex. More patients will be attending EDs for symptom control, mental distress, ease of access to healthcare and caregiver stress at their end-of-life phase (2,3), which is defined by the European Society for Emergency Medicine as patients facing a rapid deterioration in health with imminent death in an emergency medicine setting (4). Such critically ill and dying patients have significant palliative care needs that include management of moderate to severe symptoms of pain, fatigue and dyspnoea (3). Apart from infrastructural constraints due to its inherent chaotic and overcrowded environment (5,6), emergency physicians are also inadequately trained in pain and symptom management for such patients (7).

While some efforts have been undertaken to establish protocolised management pathways for ED end-of-life patients, quality of care is still not optimised and more can be done (8). To cope with changing demands in healthcare needs in the EDs, the assessment of quality of care rendered to end-of-life patients is particularly important to identify areas for improvement to ensure a good death. One such available instrument is the “Care of the Dying Evaluation” (CODETM), a shortened and validated version of “Evaluating Care and Health Outcomes – for the Dying” which measures components relating to best practice for care of the dying, previously validated in a Caucasian population within the community settings (9).

CODETM is a 40-item self-administered questionnaire that evaluates the quality of care in the last days of life and immediate post-bereavement period. Within CODETM, three constructs, ‘CARE’, ‘ENVIRONMENT’ and ‘COMMUNICATION’, are examined in detail. However, it has not been validated in a predominantly Asian population and was not administered in an ED setting. Differences in perspectives and attitudes towards end-of-life care are known to exist among various ethnic groups (10,11), and these differences may be more apparent among Asians who are generally thought to be more conservative and reserved in exploring end-of-life issues due to cultural and religious beliefs (12,13). Furthermore, the experience and interaction of patients and family members with the clinical team in ED may contrast with their regular palliative or hospice care providers as there is no pre-existing patient-physician relationship, and ED physicians are less adept at dealing with death-related issues (14). We aim to validate the use of the CODETM questionnaire in the EDs of a multi-ethnic Asian population in Singapore.

This study constitutes the pilot phase of our multi-centre study, “End-of-life Management Protocol Offered Within Emergency Room” (EMPOWER); the final and complete study protocol has been published separately (15). The objectives of this pilot were to examine the face and construct validity, and reliability of a newly developed questionnaire for measuring the quality of end-of-life care in EDs in the Asian context, taking reference from the CODETM questionnaire (9).

We present the following article in accordance with the STROBE reporting checklist (available at http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/apm-21-380).

Methods

Study design

We conducted a mixed methods study between January and April 2019 at the EDs of three public hospitals [National University Hospital (NUH), Changi General Hospital (CGH) and Khoo Teck Puat Hospital (KTPH)] in Singapore. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (as revised in 2013). Ethics approval was obtained from the National Healthcare Group Domain Specific Review Board (DSRB reference no: 2018/00838) and the study protocol was registered with ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT03906747). All enrolled participants provided written informed consent.

Study setting

The public hospitals included in this study, namely NUH, CGH and KTPH, belong to the three main healthcare clusters in Singapore – the National University Health System, Singapore Health Services and National Healthcare Group, which serve the country’s western, eastern and northern populations, respectively (16). Each of these three hospitals are tertiary centres with annual ED census of more than 100,000 attendances.

Patient selection

Next-of-kin of patients who fulfilled all the following inclusion criteria were invited to participate:

- Actively dying patient or high likelihood of mortality within the current admission (based on attending physician’s clinical judgement using available clinical data);

- Family accepts that the goals of care are provision of comfort, symptom relief and respect of dignity;

- Patient is not a candidate for cardiopulmonary resuscitation, endotracheal intubation or transfer to the intensive care unit due to medical futility from acute or underlying medical conditions (these include patients who may already have do-not-resuscitate orders established before coming to ED or after thorough assessment upon arrival to ED);

- Any of the life-limiting conditions: chronic frailty with poor functional state and limited reversibility [Karnofsky Performance Scale (KPS) <40%] (17); chronic severe illness with poor prognosis [terminal cancer, end-stage renal failure (refusal or withdrawal of dialysis), end-stage respiratory, heart or liver disease, advanced neurological disease]; or, acute severe catastrophic conditions and at risk of dying with complications that are not reversible, as subject to the treating clinician’s judgement.

We excluded the following subjects: vulnerable population (for example prisoners and pregnant women); refusal to participate; patients who have been recruited, or had declined participation during the previous ED attendance(s); patients in peri-arrest state; and/or family members who are not present at the patient’s bedside.

Study procedure

Participants, i.e., next-of-kin of end-of-life patients, were requested to complete the newly developed questionnaire renamed “Care of the Dying Evaluation - Emergency Medicine” (CODE-EM) (Appendix 1), derived using the original 40-item CODETM. The questions were selected due to their relevance to the ED settings and the other items were removed as they were not applicable in our area of practice. Wordings of the original questions were also rephrased as required to fit the ED context. Details of which questions were omitted or amended and the rationale for doing so are illustrated in Table S1. This first questionnaire completion was done at bedside in the EDs after the patients had received treatment, before or shortly after transfer to wards, terminal discharge from the EDs (where patients passed away at home) or death occurring in EDs.

After completion of the questionnaire, an interview about their experience was conducted by trained research assistants to prompt participants to articulate their thoughts (the “think-aloud” method for cognitive interviews) as they read and answered the questions (18). This helped to improve our knowledge about whether the questions had been understood and how answers had been formulated, in terms of language, length, timing and relevance. Additionally, a standard set of interview questions was asked as a combined approach to elicit its clarity and appropriateness. The key questions included in the interview are as follows:

- Were the questions easy to understand and was the wording clear?

- Did the questions make you feel emotionally distressed?

- Were any of the questions irrelevant?

- What were your thoughts on the length of this survey?

- Was the survey conducted at an appropriate timing?

- Any other feedback you would like to share?

For those who were willing to complete the questionnaire for a second time, the second interview was conducted by phone or by mail with a return envelope one month later.

Data collection

The questionnaires and interviews were conducted by trained research assistants at each study site and responses recorded real-time on standardized paper-based case report forms. Data collected is then entered anonymously into an electronic database in the Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap) system and maintained at the Singapore Clinical Research Institute’s secured server.

Statistical analysis

The interviews about the experience of completing the questionnaire was recorded. To ensure data integrity, a random selection of completed questionnaires and written interview transcripts (n=15) were independently reviewed to check for data entry errors by a study investigator (MTC) not directly involved in data collection; any discrepancy was verified and discussed with a third independent investigator (WSK).

Quantitative analysis was carried out using R, version 4.0.0 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria). The temporal stability of the developed questionnaire, CODE-EM, was assessed using the following measures: percentage agreement and κ statistic (Cohen’s for nominal response options and weighted for ordinal response options). As the kappa might not be reliable for rare observations, the criteria for good stability over time are defined as percentage agreement >70% or κ >0.60 and moderate stability over time as percentage agreement >30% or κ >0.40 (19,20). Cronbach’s α and item-total correlations were measured to assess internal consistency within the three constructs of “CARE”, “ENVIRONMENT” and “COMMUNICATION”. Confirmatory factor analysis was used to assess construct validity. The suitability of questions was examined by inspection of the Comparative Fit Index (CFI).

Results

Participants’ and patients’ characteristics

During the enrolment period, there were 18,502 eligible patient visits and 132 patients fulfilled our inclusion criteria; 102 patients were excluded due to various reasons (Figure 1). A total of 30 bereaved next-of-kin (participants) agreed to participate (76.9%). All of them completed the CODE-EM questionnaire and were interviewed in the first assessment; 22 of them (73.3%) completed the CODE-EM questionnaire a second time one month later (Table 1). Just over half of the end-of-life patients (17/30, 56.7%) were male while the participants comprised more females (16/30, 53.3%). There was a predominance of Chinese ethnicity among both patients and participants (Table 1). A summary of their baseline demographics is illustrated in Table 1. Most of the deceased patients had chronic frailty as the predominant death trajectory (19/30, 63.3%), followed by sudden death (5/30, 16.7%), cancer (4/30, 13.3%) and organ failure (2/30, 16.7%). Patients experienced multiple symptoms, with dyspnoea affecting two-thirds (20/30, 66.7%), while others experienced drowsiness (16/30, 53.3%), weakness or fatigue (11/30, 36.7%), excessive secretions (7/30, 23.3%), terminal restlessness (5/30, 16.7%), delirium (5/30, 16.7%), cough (4/30, 13.3%) and vomiting (2/30, 6.7%).

Full table

Interview results

All the participants reported a clear and easy understanding of the questionnaire with unambiguous wording. Only a minority felt that the questions made them emotionally distressed (7/30, 23.3%) (Table 1); among them, some generally felt disturbed as the questionnaire involves discussion of death and particularly in Q19 (which asks if the next-of-kin was informed that the patient would die soon) where a strongly emotive word, “die,” was used.

Seven participants (23.3%) perceived that some of the questions were irrelevant. One example was a participant who considered Q7 (which enquires if the patient appears to be in pain) extraneous as he was unable to tell if the unconscious patient was in pain and suggested that the study team tailor the questions to cater for such circumstances.

Many of the participants (27/30, 90.0%) thought the length of the survey was “just nice”, while 3 of them felt it was “too long”. Two-thirds of the participants (20/30, 66.7%) reported that the survey was conducted at an appropriate timing. For those who responded that the survey should be conducted later, there was no consensus on the best possible timing. More details on the interview answers with open questions are summarised in Table S2.

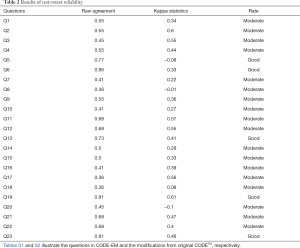

Test-retest reliability

Two statistics measuring test-retest reliability, i.e., raw agreement and kappa statistics, are reported in Table 2. Negative kappa values were obtained for Questions 5, 8 and 20, which indicate that kappa did not function well in these questions and we had to rely solely on raw agreement. Questions that explored the participants’ trust and confidence in ED nurses and doctors (Q5 and Q6), whether patients appeared to have breathing difficulty (Q13), communication regarding imminent death (Q19) and overall support given in ED (Q23) showed “good” test-retest reliability. All other questions achieved “moderate” reliability.

Full table

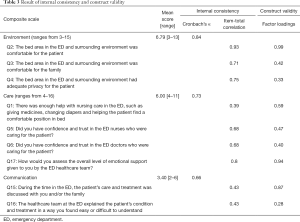

Internal consistency

The internal consistency was good for “ENVIRONMENT” (Cronbach’s α=0.84) and “CARE” (Cronbach’s α=0.73) suggesting that the inter-item correlations were high, and the items were reliable as individual scales (Table 3). However, the internal consistency of “COMMUNICATION” was moderate with a Cronbach’s α of 0.66.

Full table

Construct validity

The Comparative Fit Index (CFI) was 0.87 confirming suitability of the data for factor analysis. The factor loadings for most of the questions were relatively high, ranging from 0.40 to 0.99, except Question 16 (factor loading =0.28) and Question 4 (factor loading =0.33) (Table 3).

Discussion

The results from this pilot study support the feasibility of the use of CODETM in a culture (multi-racial Asian population) and environment (ED setting) that is vastly different from its original validation cohort (9). In our sample, CODE-EM demonstrated good face and content validity, and moderate to good test-retest reliability over time. From the results of the post-questionnaire interviews, only one question (Q19) required minor change in the wordings used, where participants expressed that the word “die” was too ‘strong’ and alternative wording was suggested. This finding is consistent with a previous local study (21). Otherwise, the CODE-EM was largely well-received by our pilot cohort and did not cause emotional distress in the vast majority despite death being considered generally taboo in the local population who have disparate cultural and religious beliefs (22,23).

We observed good internal consistency for items under “ENVIRONMENT” (Cronbach’s α=0.84) and “CARE” (Cronbach’s α=0.73). This is especially important in ED where overcrowding with packed trolleys and lack of privacy for grieving are frequent issues (6,24,25). Assessing quality of care under these 2 components will be paramount for improvement.

Asians are known to have different perspectives about death and are generally phobic of discussing death openly (22,23). While the main core constituents of a “good death” such as alleviation of pain and the need for closure remains the same among different ethnicities, there are variations in degree of importance of these elements due to underlying cultural and religious diversity that shape an individual’s experience (26). Additionally, the cultural diversity also means that death and grief experiences are handled differently among family members of various ethnicities (23). To ensure a “good death”, fulfilment of palliative care needs of imminent dying patients in the ED is becoming more pressing due to the growing number of acutely ill ageing population (27). Moreover, barriers to implementation of end-of-life care in the ED have been well recognised (5,6,28). Such challenges include a fast-paced environment with limited information at-hand, lack of rapport and relationship with patients on regular palliative care follow-up, the default “save-all” mentality among ED physicians and perceived difficulty in dealing with bereaved family members (28). In this pilot, we have shown that the CODE-EM questionnaire is a valid and reliable instrument to assess quality of end-of-life care both in the Asian context and emergency setting. Knowledge on deficiencies will facilitate future infrastructure planning and enhanced care pathways. This information can be used to improve emergency end-of-life care in various EDs across the globe.

In our pilot study, 6 out of the 7 participants who felt distressed actually commented the timing was appropriate. It is possible that bereaved next-of-kin may find it consoling and therapeutic to participate in such surveys to talk about their experience, which may aid in emotional healing and closure (29,30). Given the sensitive nature of the topic, there is no good and appropriate time, as evident by the lack of consensus among our study cohort on when is the best time. Yet, it is also important to minimise recall bias and the assessment should be conducted as early as possible.

The default focus of ED physicians is to provide aggressive care to “reverse” death, which may inadvertently lead to futile care and may not alleviate suffering of the dying (31). Understanding the perspectives of the next-of-kin using CODE-EM on how their loved ones were cared for may encourage change in practice mentality among ED physicians. Components in CODE-EM can also allow us to identify if emergency physicians are deficient in specific domains such as pain management or communications. These results can effect targeted changes in training syllabus in the emergency residency programme, with added focus and specialised courses on areas of inadequacies.

Apart from medical management, communications including addressing emotions and spiritual needs is an important component in end-of-life care. While previous qualitative studies have shown ED personnel to be lacking in such communications (32,33), our assessment tool will quantify the extent of inadequacy from the perspectives of bereaved family members. The CODE-EM questionnaire will allow us to pinpoint shortcomings in various aspects of ED palliative care, especially in terms of care, communications and infrastructure. Following this pilot, we have proceeded with a multicentre study using CODE-EM to evaluate the quality of end-of-life care provided in the ED (15). Our study findings in a multicultural Singapore will advise potential barriers and areas for improvement in palliative care among ED patients internationally.

Strengths and limitations

One of the strengths of our study include generalisability in our local population, as the ethnic distribution in our pilot mirrors the proportions of each race in Singapore (34). Also, our cohort comprised an almost equivalent proportion of male (46.7%) and female (53.3%) participants, which would give a good representation of acceptability and emotional effects from both genders.

In addition, as opposed to the original CODETM validation study in which the relatives were enrolled 2 to 3 months after bereavement (9), our participants were approached at the bedside in ED while their loved ones were acutely ill. This may add to their emotional burden but would have reduced recall bias with real-time evaluation.

Our study has its limitations. First, our sample size is relatively small with 30 participants. As this was a pilot phase of a larger prospective multi-centre study (15), our main aim was to assess feasibility and validity of using this questionnaire in our population with maximum achievable sample size within our specified timeframe. The study results showed our participants were quite representative of our local population in terms of the gender and ethnicity distribution (34). Further, we achieved a response rate of 76.9% among eligible participants based on our selection criteria and a fairly high retest participation rate of 73.3% to assess test-retest reliability. Second, although different ethnic groups have been found to have similar ease in discussing death (21), the predominance of Chinese ethnicity in our study may have resulted in under-representation of other ethnic groups. Hence, the results may not be applicable in countries with dissimilar ethnic proportions.

Third, while we tried to provide more robust data by adopting two methods of statistical testing (percentage agreement and kappa) for test-retest reliability, kappa measures showed extreme or negative values in some questions and we could only rely on raw percentage agreement. Although kappa is commonly used to measure agreement and has the advantage of not being based on probabilistic model (20), it performs poorly when marginal distributions are very asymmetric and may be difficult to interpret (35). When kappa is inadequate in certain questions, we used percentage agreement to supplement such limitation.

Fourth, we only observe moderate consistency in “COMMUNICATION”. This could be related to a slightly different angle of the questions and fewer items within this construct, as we had to ensure that the questionnaire was of an acceptable length in light of the emotional distress the participants could be facing. However, item-total scores for both Q15 and Q16 were more than 0.4, which indicated very good discrimination (36). This suggests that the items had high inter-item correlations and worked well together as individual scales.

Conclusions

This pilot study shows CODE-EM may be a valid and reliable evaluation tool for assessing quality of end-of-life care among Asian ED patients. It may help us understand the perspectives of the bereaved next-of-kin on the quality of end-of-life care rendered in the EDs and in a real-time fashion at patients’ bedside, minimising recall bias. Our prospective multicentre study will further advise current barriers so that improvements can be made to better end-of-life care for ED patients internationally.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank our research coordinators, Ms Eileen Tay, Ms Wei Lin Chua and Ms Lina Amirah Amir Ali for their assistance in the conduct of this study, and our colleagues at the emergency departments of National University Hospital, Changi General Hospital and Khoo Teck Puat Hospital for their support.

Funding: This study was funded by the National Medical Research Council’s Health Services Research Grant, from Ministry of Health, Singapore. The grant was awarded to Dr. Rakhee Yash Pal (grant number: HSRG-EoL17Jun001).

Footnote

Reporting Checklist: The authors have completed the STROBE reporting checklist. Available at http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/apm-21-380

Data Sharing Statement: Available at http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/apm-21-380

Peer Review File: Available at http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/apm-21-380

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/apm-21-380). CRM is funded by a Yorkshire Cancer Research ‘CONNECTS’ Fellowship. RYP reports grants from the National Medical Research Council, Ministry of Health, Singapore. The other authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (as revised in 2013). The study was approved by the National Healthcare Group Domain Specific Review Board (DSRB reference no: 2018/00838) and informed consent was taken from all individual participants.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division. World Popul Ageing 2017 - Highlights 2017.

- Smith AK, McCarthy E, Weber E, et al. Half of older Americans seen in emergency department in last month of life; most admitted to Hospital, and many die there. Health Aff (Millwood) 2012;31:1277-85. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Grudzen CR, Richardson LD, Morrison M, et al. Palliative Care Needs of Seriously Ill, Older Adults Presenting to the Emergency Department. Acad Emerg Med 2010;17:1253-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- European Society for Emergency Medicine. European recommendations for end-of-life care for adults in Departments of Emergency Medicine. 2017.

- Gloss K. End of life care in emergency departments: a review of the literature. Emerg Nurse 2017;25:29-38. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Beckstrand RL, Wood RD, Callister LC, et al. Emergency nurses’ suggestions for improving end-of-life care obstacles. J Emerg Nurs 2012;38:e7 [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Smith AK, Fisher J, Schonberg MA, et al. Am I Doing the Right Thing? Provider Perspectives on Improving Palliative Care in the Emergency Department. Ann Emerg Med 2009;54:86-93.e1. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Chor WPD, Wong SYP, Ikbal MFBM, et al. Initiating End-of-Life Care at the Emergency Department: An Observational Study. Am J Hosp Palliat Care 2019;36:941-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Mayland CR, Lees C, Germain A, et al. Caring for those who die at home: The use and validation of “Care Of the Dying Evaluation” (CODE) with bereaved relatives. BMJ Support Palliat Care 2014;4:167-74. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Barnato AE, Anthony DL, Skinner J, et al. Racial and Ethnic Differences in Preferences for End-of-Life Treatment. J Gen Intern Med 2009;24:695-701. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Johnson KS, Kuchibhatla M, Tulsky JA. What Explains Racial Differences in the Use of Advance Directives and Attitudes Toward Hospice Care? J Am Geriatr Soc 2008;56:1953-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Phua J, Kee ACL, Tan A, et al. End-of-life care in the general wards of a Singaporean hospital: An Asian perspective. J Palliat Med 2011;14:1296-301. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Dutta O, Lall P, Patinadan PV, et al. Patient autonomy and participation in end-of-life decision-making: An interpretive-systemic focus group study on perspectives of Asian healthcare professionals. Palliat Support Care 2020;18:425-430. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lamba S, Mosenthal AC. Hospice and Palliative Medicine: A Novel Subspecialty of Emergency Medicine. J Emerg Med 2012;43:849-53. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Yash Pal R, Kuan WS, Tiah L, et al. End-of-life management protocol offered within emergency room (EMPOWER): study protocol for a multicentre study. BMJ Open 2020;10:e036598 [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Poon CH. Public healthcare sector to be reorganised into 3 integrated clusters, new polyclinic group to be formed. The Straits Times 2017. Available online: https://www.straitstimes.com/singapore/health/public-healthcare-sector-to-be-reorganised-into-3-integrated-clusters-new

- Karnofsky D, Burchenal J. The clinical evaluation of chemotherapeutic agents in cancer. Eval Chemother Agents 1949;191-205.

- Lee J. Conducting cognitive interviews in cross-national settings. Assessment 2014;21:227-40. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Landis JR, Koch GG. The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics 1977;33:159. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Viera AJ, Garrett JM. Understanding interobserver agreement: the kappa statistic. Fam Med 2005;37:360-3. [PubMed]

- Wee HL, Li SC, Xie F, et al. Are Asians comfortable with discussing death in health valuation studies? A study in multi-ethnic Singapore. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2006;4:93. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Braun KL. Death and dying in four Asian American cultures: a descriptive study. Death Stud 1997;21:327-59. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Yick AG, Gupta R. Chinese cultural dimensions of death, dying, and bereavement: focus group findings. J Cult Divers 2002;9:32. [PubMed]

- Trzeciak S. Emergency department overcrowding in the United States: an emerging threat to patient safety and public health. Emerg Med J 2003;20:402-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Beckstrand RL, Rasmussen RJ, Luthy KE, et al. Emergency nurses’ perception of department design as an obstacle to providing end-of-life care. J Emerg Nurs 2012;38:e27-e32. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Krikorian A, Maldonado C, Pastrana T. Patient’s Perspectives on the Notion of a Good Death: A Systematic Review of the Literature. J Pain Symptom Manage 2020;59:152-64. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Emanuel EJ, Emanuel LL. The promise of a good death. Lancet 1998;351:SII21-SII29. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Chan GK. End-of-life models and emergency department care. Acad Emerg Med 2004;11:79-86. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Koffman J, Higginson IJ, Hall S, et al. Bereaved relatives’ views about participating in cancer research. Palliat Med 2012;26:379-83. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Germain A, Mayland CR, Jack BA. The potential therapeutic value for bereaved relatives participating in research: An exploratory study. Palliat Support Care 2016;14:479-87. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Marck CH, Weil J, Lane H, et al. Care of the dying cancer patient in the emergency department: findings from a National survey of Australian emergency department clinicians. Intern Med J 2014;44:362-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Zhang Y, Yash Pal R, Tam WSW, et al. Spiritual perspectives of emergency medicine doctors and nurses in caring for end-of-life patients: A mixed-method study. Int Emerg Nurs 2018;37:13-22. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- McBrien B. Nurses’ provision of spiritual care in the emergency Setting – An Irish Perspective. Int Emerg Nurs 2010;18:119-26. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Population in brief. Strateg Group, Singapore. Available online: https://www.strategygroup.gov.sg/media-centre/publications/population-in-brief

- Delgado R, Tibau XA. Why Cohen’s Kappa should be avoided as performance measure in classification. PLoS One 2019;14:e0222916 [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Pope G. Psychometrics 101: Item Total Correlation. Available online: https://www.questionmark.com/item-total-correlation/