Mental health status and quality of life in patients with end-stage renal disease undergoing maintenance hemodialysis

Introduction

Maintenance hemodialysis is one of the main replacement treatments for end-stage renal disease (ESRD) and has prolonged patient life (1). Due to that the chronic kidney diseases (CKD) increase gradually, the number of patients who require dialysis increase annually (2). However, hemodialysis is a time-consuming procedure and may cause psychological distress, despite the good condition of their physical health (3). Previous study indicated that psychological problems were common among ESRD patients undergoing maintenance hemodialysis, especially depression (4). A high frequency of depression has been reported in patients treated for ESRD with dialysis (5), which is independently related with significantly increasing risk of both morbidity and mortality (6). Psychological problems have affected the progression and outcome of patients with chronic kidney disease (7-9), which is a more prominent problem among ESRD patients with maintenance dialysis (10).

Furthermore, ESRD has contributed to high medical costs, which becomes a heavy burden of public health (11). Psychological issues represent one of the most common health problems affecting the survival in patients undergoing maintenance hemodialysis (12). Identifying the relative factors of psychological issues in such population and then adopting treatments may help improve treatment outcomes for those patients, therefore, reducing the costs of national burden. Previous study indicated diabetic patients with CKD were more likely to have a major depressive episode when comparing with nondiabetic patients with CKD (5). However, limited researches on identifying relative factors of poor mental health status among such patients.

Many studies have showed that the survival rate of ESRD patients undergoing maintenance hemodialysis had improved (13-15), but when compared with the general population, the quality of life (QOL) of ESRD patients undergoing maintenance hemodialysis remained poor (16). QOL is the patient’s subjective experience of physical, mental, and social health, and reflects the state of the patient’s health, determines prognoses, and guides clinical practice (17). ESRD patients undergoing maintenance hemodialysis suffer from severe disease symptoms and psychological burdens that can have a profound impact on QOL (18). Psychological issues represent one of the most common health problems affecting the QOL in patients undergoing maintenance hemodialysis (12). Therefore, improving the mental health status may help to improve the QOL among such population.

Currently, several studies have used the Chinese version symptom checklist-90 (SCL-90), the multidimensional psychological self-rated scale to measure psychological health among the population (19). Chinese version SCL-90 is a 90-item symptom scale that focus on feeling, thinking, behavior, interpersonal relationships, living habits, diet, sleep, and other relevant aspects (20). The main purpose is to assess whether a person has a certain psychological symptom, and how severe it is.

We conducted an observational, cross-sectional study to identify the relative factors of poorer mental health status and examinate the correlation between mental health status and QOL among ESRD patients undergoing maintenance hemodialysis.

We present the following article in accordance with the STROBE reporting checklist (available at http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/apm-20-2211).

Methods

Study design and population

This study is a cross-sectional, observational one. Those who were aged over 18 years and undergoing maintenance hemodialysis for over 3 months at the time of the study were examined. Patients were excluded if they (I) had an indwelling catheter; (II) had untreated malignant tumors; (III) had some form of cognitive impairment; (IV) were unable to complete the scale; and (V) provided incomplete clinical data. Finally, a total of 190 patients were collected from a single center of hemodialysis in the Shanghai Ninth People’s Hospital, Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine. The study was conducted between August and December 2019.

Ethical considerations

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (as revised in 2013). This study was approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of the Ninth People’s Hospital, Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine (Ethics No. SH9H-2019-T143-1), and was registered with the Chinese Clinical Trials Registry (No. ChiCTR1900028275). All patients in this study signed informed consent forms after thoroughly reading and accepting its contents.

Measures and data collection

Each patient had a face-to-face interview which lasted 30–45 min in a private room. All interviews for all patents were using the Chinese version of SCL-90 and the Chinese version KDQOL-SF questionnaire, and all interviews were made by Shao-Jun Ma who was trained by professionals.

We collected the patients’ self-reported sociodemographic data, medical history and laboratory data from electronic medical records. A set of the following clinical parameters was analyzed: age, sex (male or female), educational level(under high school or high school or above), marital status(married or widowed or bachelor), duration of hemodialysis (<2 or ≥2 years), pre-dialysis systolic pressure, pre-dialysis diastolic pressure, heart rate; laboratory data of serum: prealbumin, albumin, pre-dialysis blood urea nitrogen, sodium, potassium, chlorine, calcium, phosphorus, magnesium, hemoglobin, total cholesterol, triglyceride, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, hemoglobin A1C; medical history: presence or absence of stroke, presence or absence of coronary artery disease, presence or absence of type 2 diabetes mellitus, presence or absence of hypertension, presence or absence of heart failure, kinds of anti-hypertension drugs and use of psychotropic medicine (no or yes).

Chinese version SCL-90

Chinese version SCL-90 comprises 10 psychiatric factors, namely depression, anxiety, somatization, phobic, paranoid, obsessive compulsive, interpersonal sensitivity, hostility, psychoticism, and other factors such as sleep and diet (20). Each item was scored using a 5-point scale (0= none, 1= slight, 2= mild, 3= moderate, 4= severe) (21). This scale suggested the score of a positive item was more than 2, which may indicate potential mental health issues (20).

Chinese version kidney disease quality of life-short form (KDQOL-SF, Version 1.3)

We used the Chinese version KDQOL-SF, Version 1.3 (22) to assess the patient’s QOL in two parts. One part of this scale evaluates the QOL across 12 fields in kidney disease-targeted areas (KDTA). Another part assesses the general QOL across 8 fields using a 36-item health survey (SF-36). The KDTA covered the following areas: symptoms/problems, effects of kidney disease on daily life (EKD), burden of kidney disease, work status, cognitive function, quality of social interaction, sleep, social support, sexual function, dialysis staff encouragement, patient satisfaction, and overall health rating. The SF-36 scale covered physical functioning, role limitations-physical health, bodily pain, general health perception, social functioning, role limitations-emotional, mental health, and vitality. The physical component summary (PCS) included physical functioning, role limitations-physical health, bodily pain and general health perception; the mental component summary (MCS) included social functioning, role limitations-emotional, mental health, and vitality. The scoring standard and method of KDQOL-SF, Version 1.3 referenced the scoring criteria in Hays et al. (23). The scores on each scale range from 0 to 100. The higher the scores, the better the QOL. The overall health rating item allowed patients to rate their health on a response scale ranging from 0 (“worst possible health”) to 10 (“best possible health”) (23).

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS 24.0. The data were displayed in the format of a number (%) or mean (standard deviation), and the counting data were expressed by frequency. The t test was used for the continuous variables. The associations were examined by using multiple stepwise linear regression analyses, and the coefficients and 95% confidence interval (CI) for each significant variable were determined. The variables including patients’ age, sex, educational level, marital status, duration of hemodialysis, pre-dialysis systolic pressure, pre-dialysis diastolic pressure, heart rate, prealbumin, albumin, pre-dialysis blood urea nitrogen, sodium, potassium, chlorine, calcium, phosphorus, magnesium, hemoglobin, total cholesterol, triglyceride, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, hemoglobin A1C, stroke, coronary artery disease, type 2 diabetes mellitus, hypertension, heart failure, kinds of anti-hypertension drugs and use of psychotropic medicine were entered in all multiple stepwise linear regression analyses. Pearson correlation analysis was used for correlation analysis, P<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

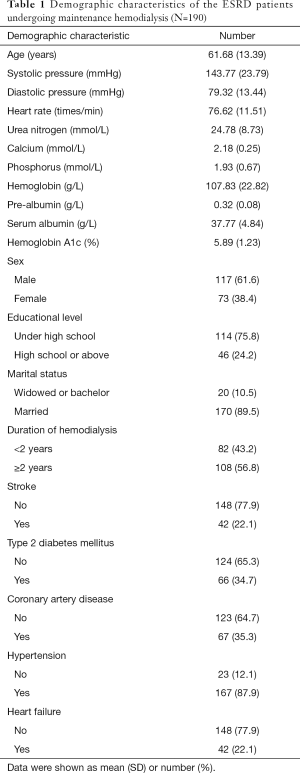

Among the 200 patients, 10 dropped out while filling the forms, and 190 completed the Chinese version SCL-90, the Chinese version KDQOL-SF (Figure 1). Most patients did not respond to the Chinese version KDQOL-SF questions on sexual function, dialysis staff encouragement, and patient satisfaction for they may have thought that the above items were private. Values of these scales were reported as missing data, according to the KDQOL-SF scoring instructions. The average age in the total patients was 61.68 (13.39) years and the gender ratio (male/ female) was 117/ 73. The demographic characteristics of the patients are presented in Table 1.

Full table

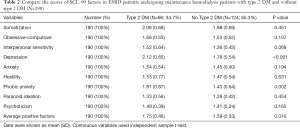

In univariate analysis, the average positive factors were 1.75 (0.46) and 1.58 (0.33) for participants with and without type 2 diabetes mellitus, respectively (P=0.010); the scores of depression factor were 2.12 (0.65) and 1.78 (0.54) for participants with and without type 2 diabetes mellitus, respectively (P<0.001); the scores of phobic anxiety factor were 1.81 (0.87) and 1.43 (0.64) for participants with and without type 2 diabetes mellitus, respectively (P=0.002). The results of univariate analyses are shown in Table 2, Tables S1-S4.

Full table

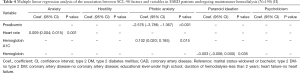

Multiple stepwise linear regression analyses suggested that when controlling for the confounding variables, prealbumin had the significant influence on average positive factors (Coef., −0.647; 95% CI: −1.314, 0.020; P=0.057), somatization (Coef., −1.334; 95% CI: −2.451, −0.217; P=0.020), obsessive-compulsive (Coef., −1.396; 95% CI: −2.255, −0.537; P=0.002), depression (Coef., −1.241; 95% CI: −2.252, −0.229; P=0.017), phobic anxiety (Coef., −2.576; 95% CI: −3.786, −1.367; P<0.001); comorbid type 2 diabetes mellitus had the significant influence on average positive factors (Coef., 0.131; 95% CI: 0.015, 0.248; P=0.027), depression (Coef., 0.283; 95% CI: 0.105, 0.460; P=0.002), interpersonal sensitivity (Coef., 0.156; 95% CI: 0.008, 0.304; P=0.039); heart rate had the significant influence on average positive factors (Coef., 0.005; 95% CI: 0.001, 0.010; P=0.023), obsessive-compulsive (Coef., 0.006; 95% CI: 0.000, 0.013; P=0.003), interpersonal sensitivity (Coef., 0.010; 95% CI: 0.003, 0.016; P=0.003), depression (Coef., 0.008; 95% CI: 0.001, 0.015; P=0.028), anxiety (Coef., 0.009; 95% CI: 0.004, 0.015; P=0.001); educational level had the significant influence on average positive factors (Coef., −0.131; 95% CI: −0.257, −0.005; P=0.041), obsessive-compulsive (Coef., −0.245; 95% CI: −0.414, −0.076; P=0.005), interpersonal sensitivity (Coef., −0.175; 95% CI: −0.341; −0.009; P=0.039); comorbid coronary artery disease had the significant influence on somatization (Coef., 0.231; 95% CI: 0.035, 0.426; P=0.021); duration of hemodialysis had the significant influence on somatization (Coef., 0.247; 95% CI: 0.058, 0.436; P=0.011); comorbid heart failure had the significant influence on somatization (Coef., 0.241; 95% CI: 0.010, 0.472; P=0.041); marital status had the significant influence on depression (Coef., −0.280; 95% CI: −0.544, −0.015; P=0.038); hemoglobin A1C had the significant influence on phobic anxiety (Coef., 0.102; 95% CI: 0.020, 0.185; P=0.015); hemoglobin had the significant influence on paranoid ideation (Coef., −0.003; 95% CI: −0.006; 0.000; P=0.035). The results of multiple stepwise linear regression analyses are presented in Tables 3,4.

Full table

Full table

Table 5 and Table S5 listed the correlation between each score of the Chinese version SCL-90 and the Chinese version KDQOL-SF. The score of average positive factors was significantly correlated with the score of the overall health rating (Coef., −0.343; P<0.001), symptom/problem (Coef., −0.337; P<0.001), effects of kidney disease on daily life (Coef., −0.198; P=0.006), burden of kidney disease (Coef., −0.233; P=0.001), cognitive function (Coef., 0.363; P<0.001), quality of social interaction (Coef., 0.292; P<0.001), social support (Coef., 0.237; P=0.001), physical functioning (Coef., −0.339; P<0.001), pain (Coef., 0.362; P<0.001), general health (Coef., −0.332; P<0.001), mental health (Coef., −0.537; P<0.001), social functioning (Coef., 0.202; P=0.005), vitality (Coef., −0.478; P<0.001), respectively. The description of categorical variables of ESRD patients undergoing maintenance hemodialysis is shown in the Table S6. The scores of the Chinese version SCL-90 nine factors and Chinese version KDQOL-SF domains are shown in the Tables S7 and S8.

Full table

Discussion

Our findings suggested that prealbumin, type 2 diabetes mellitus, heart rate, educational level, duration of hemodialysis, coronary artery disease, heart failure, marital status, hemoglobin A1C and hemoglobin were significantly related with poorer mental health status of ESRD patients undergoing maintenance hemodialysis, and patients with poorer psychological states were more significantly associated with decreased QOL. For the scores of SCL-90 nine factors, they were negatively correlated with the score of several KDQOL-SF fields respectively; higher scores of SCL-90 factors represented potential mental health issues. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to identify the relative factors of the psychological states and examine the association between the psychological states and QOL among ESRD patients undergoing maintenance hemodialysis.

Currently, approximately 3 million people worldwide have been taking renal replacement therapy mostly in the form of hemodialysis (24), which significantly improved the long-term survival of the ESRD patients. However, several studies have reported that the patients with hemodialysis have an unusual psychological state, which can cause severe depression (25,26).

Previous studies indicated that about one third of patients undergoing maintenance hemodialysis had depressive symptoms, which effective treatments need to be identified (27,28).Therefore, identifying the relative factors of psychological symptoms among such patients may help clinicians to adopt an effective treatment for early interventions. In our results, comorbid type 2 diabetes mellitus had the negative influence on average positive factors, depression and interpersonal sensitivity of SCL-90, which was consistent with previous study indicating that diabetes was an independently risk factors for diabetic patients with CKD that were more likely to have a major depressive episode when comparing with nondiabetic patients with CKD (5). In addition, our study also found that for ESRD patients undergoing maintenance hemodialysis, prealbumin, hemoglobin, comorbid heart failure and comorbid coronary artery disease were significantly associated with the mental health status, respectively, which was consistent with previous studies (29,30). Besides, faster heart rate, longer duration of hemodialysis, educational level and patients married were significant relative factors, which may be a useful basis for clinical practice; our study indicated that hemoglobin A1C, prealbumin and hemoglobin were statistically significant factors of poorer mental health, but lack the biological meaning.

QOL has become an important index for the comprehensive evaluation (31). Assessing the QOL of ESRD patients undergoing maintenance hemodialysis can help clinicians understand the general condition of patients, therefore, can guide administrations towards specific, context-sensitive, and appropriate interventions to promote this population’ QOL, which could prevent the progress of psychological issues and ultimately improve the QOL. Several studies have shown that the QOL of patients undergoing maintenance hemodialysis is generally lower than the general population (32,33). Published study indicated that emotional symptoms are related directly with impaired QOL in patients undergoing maintenance hemodialysis (34). Our study suggested that patients undergoing maintenance hemodialysis with poorer psychological states were more significantly associated with decreased QOL, which was consistent with previous studies. Therefore, to improve the QOL of such patients, it is necessary to adopt a standard assessment of symptoms into the care, which comprehensively reflects the possible psychological problems of patients and to select reasonable and appropriate measures for intervention.

However, our study has some limitations. First, our study was limited by its small sample size for the data were from a single hospital. Second, a cross-sectional design makes it impossible to infer the causal relationship among different mental health status and QOL; thus, longitudinal studies are needed to examine the relationship over time (17). Thirdly, almost all patients enrolled refused to answer the same 3 categories of questionnaire, which might exist some degree of interviewer bias. Finally, this is a questionnaire-based survey, personal fear or prejudice toward the evaluation may distort the data further; and the results might have been negatively affected by acquiescence bias and social desirability bias (35).

Acknowledgments

We are thanks to Medical English Editing Service (

Funding: This study was supported, in part, by grants from National Natural Science Foundation of China (No: 81870462, 81470990), the Science and Technology Commission of Shanghai Municipality (No: 17441904200, 19441909300), Shanghai Ninth People’s Hospital Clinical Research Program (No: JYLJ007), Shanghai Ninth People’s Hospital MDT Program (2017-1-019).

Footnote

Reporting Checklist: The authors have completed the STROBE reporting checklist. Available at http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/apm-20-2211

Data Sharing Statement: Available at http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/apm-20-2211

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/apm-20-2211). The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (as revised in 2013). This study was approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of the Ninth People’s Hospital, Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine (Ethics No. SH9H-2019-T143-1), and was registered with the Chinese Clinical Trials Registry (No. ChiCTR1900028275). All patients in this study signed informed consent forms after thoroughly reading and accepting its contents.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- Kalantar-Zadeh K, Crowley ST, Beddhu S, et al. Renal Replacement Therapy and Incremental Hemodialysis for Veterans with Advanced Chronic Kidney Disease. Semin Dial 2017;30:251-61. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Zhou X, Xue F, Wang H, et al. The quality of life and associated factors in patients on maintenance hemodialysis - a multicenter study in Shanxi province. Ren Fail 2017;39:707-11. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Iacovides A, Fountoulakis KN, Balaskas E, et al. Relationship of age and psychosocial factors with biological ratings in patients with end-stage renal disease undergoing dialysis. Aging Clin Exp Res 2002;14:354-60. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Sumanathissa M, De Silva VA, Hanwella R. Prevalence of major depressive episode among patients with pre-dialysis chronic kidney disease. Int J Psychiatry Med 2011;41:47-56. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hedayati SS, Minhajuddin AT, Toto RD, et al. Prevalence of major depressive episode in CKD. Am J Kidney Dis 2009;54:424-32. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hedayati SS, Bosworth HB, Briley LP, et al. Death or hospitalization of patients on chronic hemodialysis is associated with a physician-based diagnosis of depression. Kidney Int 2008;74:930-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Cukor D, Cohen SD, Peterson RA, et al. Psychosocial aspects of chronic disease: ESRD as a paradigmatic illness. J Am Soc Nephrol 2007;18:3042-55. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kimmel PL. Psychosocial factors in adult end-stage renal disease patients treated with hemodialysis: correlates and outcomes. Am J Kidney Dis 2000;35:S132-40. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kimmel PL. Psychosocial factors in chronic kidney disease patients. Semin Dial 2005;18:71-2. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kimmel PL. Psychosocial factors in dialysis patients. Kidney Int 2001;59:1599-613. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bello AK, Levin A, Tonelli M, et al. Assessment of global kidney health care status. JAMA 2017;317:1864-81. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- He S, Zhu J, Jiang W, et al. Sleep disturbance, negative affect and health-related quality of life in patients with maintenance hemodialysis. Psychol Health Med 2019;24:294-304. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kalantar-Zadeh K, Unruh M, Zager PG, et al. Twice-weekly and incremental hemodialysis treatment for initiation of kidney replacement therapy. Am J Kidney Dis 2014;64:181-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Liem YS, Wong JB, Hunink MG, et al. Comparison of hemodialysis and peritoneal dialysis survival in The Netherlands. Kidney Int 2007;71:153-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Han SS, Park JY, Kang S, et al. Dialysis Modality and Mortality in the Elderly: A Meta-Analysis. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2015;10:983-93. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Mapes DL, Bragg-Gresham JL, Bommer J, et al. Health-related quality of life in the Dialysis Outcomes and Practice Patterns Study (DOPPS). Am J Kidney Dis 2004;44:54-60. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- AlRuthia Y, Sales I, Almalag H, et al. The Relationship Between Health-Related Quality of Life and Trust in Primary Care Physicians Among Patients with Diabetes. Clin Epidemiol 2020;12:143. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ravindran A, Sunny A, Kunnath RP, et al. Assessment of Quality of Life among End-Stage Renal Disease Patients Undergoing Maintenance Hemodialysis. Indian J Palliat Care 2020;26:47-53. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Derogatis LR, Rickels K, Rock AF. The SCL-90 and the MMPI: A step in the validation of a new self-report scale. Br J Psychiatry 1976;128:280-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wei Y, Li H, Wang H, et al. Psychological Status of Volunteers in a Phase I Clinical Trial Assessed by Symptom Checklist 90 (SCL-90) and Eysenck Personality Questionnaire (EPQ). Med Sci Monit 2018;24:4968-73. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Tang M, Wang SH, Li HL, et al. Mental health status and quality of life in elderly patients with coronary heart disease. PeerJ 2021;9:e10903 [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Chow SKY, Tam BML. Is the kidney disease quality of life-36 (KDQOL-36) a valid instrument for Chinese dialysis patients? BMC Nephrol 2014;15:199. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hays RD, Kallich JD, Mapes DL, et al. Kidney Disease Quality of Life Short Form (KDQOL-SF), Version 1.3: a manual for use and scoring. Santa Monica, CA: Rand 1997;39.

- Luyckx VA, Tonelli M, Stanifer JW. The global burden of kidney disease and the sustainable development goals. Bull World Health Organ 2018;96:414-22D. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lou X, Li Y, Shen H, et al. Physical activity and somatic symptoms among hemodialysis patients: a multi-center study in Zhejiang, China. BMC Nephrol 2019;20:477. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Mehrotra R, Cukor D, Unruh M, et al. Comparative efficacy of therapies for treatment of depression for patients undergoing maintenance hemodialysis: A randomized clinical trial. Ann Intern Med 2019;170:369-79. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Palmer S, Vecchio M, Craig JC, et al. Prevalence of depression in chronic kidney disease: systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Kidney Int 2013;84:179-91. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Flythe JE, Hilliard T, Castillo G, et al. Symptom prioritization among adults receiving in-center hemodialysis: A mixed methods study. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2018;13:735-45. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Keller T, Wanner C, Krane V, et al. Prognostic Value of High-Sensitivity Versus Conventional Cardiac Troponin T Assays Among Patients With Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus Undergoing Maintenance Hemodialysis. Am J Kidney Dis 2018;71:822-30. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Solbu MD, Mjoen G, Mark PB, et al. Predictors of atherosclerotic events in patients on haemodialysis: post hoc analyses from the AURORA study. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2018;33:102-12. [PubMed]

- Brown MA, Collett GK, Josland EA, et al. CKD in elderly patients managed without dialysis: survival, symptoms, and quality of life. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2015;10:260-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Albatineh AN, Ibrahimou B. Factors associated with quality-of-life among Kuwaiti patients on maintenance hemodialysis. Psychol Health Med 2019;24:1005-14. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Liebman S, Li N-C, Lacson E. Change in quality of life and one-year mortality risk in maintenance dialysis patients. Quality of Life Research 2016;25:2295-306. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Weisbord SD, Fried LF, Arnold RM, et al. Prevalence, severity, and importance of physical and emotional symptoms in chronic hemodialysis patients. J Am Soc Nephrol 2005;16:2487-94. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bowling A. Mode of questionnaire administration can have serious effects on data quality. J Public Health (Oxf) 2005;27:281-91. [Crossref] [PubMed]