Trends in population mortality rates in the United States from 1969 to 2017

Introduction

The causes of human death have always been a concern among clinicians and the public. Understanding the changes in the causes of death over the past five decades is worthwhile for reducing the overall mortality. Fundamental transformations in overall population health have occurred in the past five decades and are continuing. However, few studies have systematically documented these transitions at the national levels (1). In this article, we provide the numbers of deaths and analyze the national age-adjusted mortality rates between 1969 and 2017 in the United States (U.S.). This data can be an important source of public health information when data on disease incidence are unavailable, helping public health professionals and policymakers understand the national health priorities in every country.

We present the following article in accordance with the STROBE reporting checklist (available at https://dx.doi.org/10.21037/apm-21-2835).

Methods

Mortality data

The Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) database is an open-access resource for cancer-based epidemiology and survival analyses, which also has mortality data for all diseases. The U.S. mortality data, collected and maintained by the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS), can be analyzed using the SEER*Stat software. The NCHS granted the SEER program limited permission to provide the mortality data to the public. The data on mortality for all diseases were collected from the SEER Database of Mortality-All cause of death (COD), Aggregated Total U.S. [1969–2017] <Katrina/Rita Population Adjustment>. The underlying mortality data are provided by the NCHS (www.cdc.gov/nchs). The data includes all causes of death, not just cancer deaths. A total of 109,836,044 deaths from 1969 to 2017 are registered in this database.

Causes of death were classified according to the International Classification of Diseases (ICD) (2). All cancer cases were classified according to the Site Recode ICD-O-3/ World Health Organization (WHO) 2008 (2).

Statistical analysis

Mortality rates and 95% confidence intervals (CI) were age-adjusted using the 2000 U.S. Standard Population and were expressed per 100,000 person-years (2,3). Annual rates are represented graphically as trends. Temporal trends in disease mortality rates were examined, and separate analyses were conducted for males and females. We also calculated the age-adjusted mortality rates according to race/ethnicity (white, black, and other) and age group (birth to 39, 40–49, 50–59, 60–69, and ≥70 years) (4,5). All data analyses were performed using the SEER*Stat software version 8.3.6 (2,3).

Ethical considerations

Ethical approval was exempted by the Medical Ethics Committee of the First Affiliated Hospital, Zhejiang University School of Medicine (Hangzhou, China), as SEER is a publicly available database, and the data extracted from SEER were identified as a non-human study. All patient data were anonymized. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (as revised in 2013).

Results

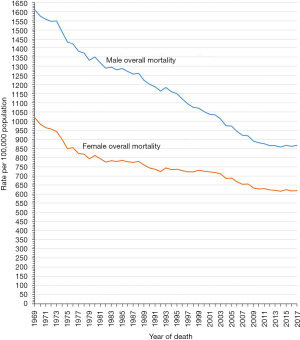

Trends in disease mortality rates by sex

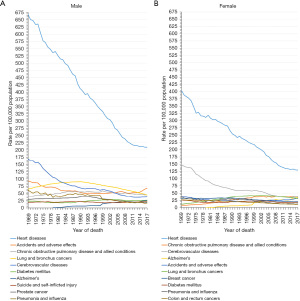

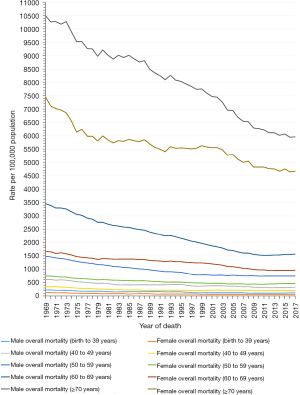

The mortality and percentage changes from 1969 to 2017 of the 20 leading causes of death in the U.S. in 2017 are shown in Table 1. From 1969 to 2017, the mortality rates of all causes of death were higher for males than females (Figure 1), and had declined continuously in both sexes (Figure 1). The male and female mortality rates of all causes of death fell by 46.1% and 39.3%, from 1,610.0 and 1,019.3 (per 100,000 population) in 1969 to 867.2 and 619.2 (per 100,000 population) in 2017, respectively (Table 1 and Figure 1). Heart diseases, accidents and adverse effects, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and allied conditions, cerebrovascular diseases, as well as lung and bronchus cancers (in males) or Alzheimer’s (in females) were the five leading causes of death in 2017 (Table 1 and Figure 2A,2B). Although it remained the leading cause of death among both sexes in the U.S. from 1969 to 2017, the age-adjusted mortality for heart diseases in males and females dropped by 68.6% and 68.0%, from 668.2 and 404.4 (per 100,000 population) in 1969 to 209.6 and 129.4 (per 100,000 population) in 2017, respectively (Table 1 and Figure 2A,2B). Similarly, from 1969 to 2017, the cerebrovascular disease mortality rate decreased by 77.3% and 75.3%, from 168.4 and 147.9 (per 100,000 population) to 38.2 and 36.6 (per 100,000 population), in males and females, respectively (Table 1 and Figure 2A,2B).

Table 1

| All causes | Mortality rank | Age-adjusted mortality rate (95% CI) | Death count | Relative change in mortality (2017 vs. 1969) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1969 | 2017 | 1969 | 2017 | 1969 | 2017 | |||||

| Males | ||||||||||

| All causes of death | 1,610.0 (1,606.6–1,613.3) | 867.2 (865.7–868.6) | 1,080,519 | 1,439,020 | −46.1% | |||||

| Heart diseases | 1 | 1 | 668.2 (666.0–670.4) | 209.6 (208.9–210.3) | 421,729 | 347,854 | −68.6% | |||

| Accidents and adverse effects | 3 | 2 | 93.7 (93.0–94.4) | 67.8 (67.4–68.2) | 80,639 | 109,708 | −27.6% | |||

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and allied conditions | 6 | 3 | 39.0 (38.5–39.5) | 45.2 (44.9–45.6) | 26,857 | 74,999 | 15.9% | |||

| Lung and bronchus cancers | 4 | 4 | 65.0 (64.4–65.6) | 44.5 (44.2–44.8) | 50,393 | 78,694 | −31.5% | |||

| Cerebrovascular diseases | 2 | 5 | 168.4 (167.2–169.5) | 38.2 (37.8–38.5) | 94,203 | 61,644 | −77.3% | |||

| Diabetes mellitus | 11 | 6 | 23.7 (23.3–24.1) | 26.9 (26.6–27.1) | 15,682 | 46,301 | 13.5% | |||

| Alzheimer’s | – | 7 | – | 25.0 (24.8–25.3) | – | 37,324 | – | |||

| Suicide and self-inflicted injury | 14 | 8 | 19.4 (19.1–19.7) | 22.4 (22.2–22.7) | 15,854 | 36,779 | 15.5% | |||

| Prostate cancer | 9 | 9 | 29.6 (29.1–30.1) | 18.9 (18.6–19.1) | 16,834 | 30,486 | −36.1% | |||

| Pneumonia and influenza | 5 | 10 | 61.4 (60.7–62.1) | 16.6 (16.4–16.8) | 37,850 | 26,557 | −73.0% | |||

| Colon and rectum cancers | 7 | 11 | 33.2 (32.7–33.7) | 16.0 (15.8–16.2) | 22,044 | 27,797 | −51.8% | |||

| Nephritis, nephrotic syndrome and nephrosis | 20 | 12 | 10.3 (10.0–10.6) | 15.8 (15.6–16.0) | 6,894 | 25,744 | 53.4% | |||

| Chronic liver disease and cirrhosis | 10 | 13 | 23.8 (23.4–24.1) | 14.4 (14.3–14.6) | 19,372 | 26,450 | −39.5% | |||

| Pancreatic cancer | 17 | 14 | 14.1 (13.8–14.4) | 12.9 (12.7–13.1) | 9,931 | 22,919 | −8.5% | |||

| Septicemia | 37 | 15 | 2.1 (2.0–2.2) | 11.7 (11.6–11.9) | 1,650 | 19,603 | 457.1% | |||

| Homicide and legal intervention | 18 | 16 | 13.7 (13.4–13.9) | 10.1 (10.0–10.3) | 12,154 | 16,109 | −26.3% | |||

| Symptoms, signs and ill-defined conditions | 12 | 17 | 21.2 (20.9–21.6) | 9.5 (9.4–9.7) | 15,717 | 15,380 | −55.2% | |||

| Hypertension without heart disease | 26 | 17 | 7.5 (7.2–7.7) | 9.5 (9.4–9.7) | 4,337 | 15,742 | 26.7% | |||

| Leukemia | 19 | 19 | 11.3 (11.1–11.6) | 8.2 (8.1–8.4) | 8,256 | 13,618 | −27.4% | |||

| Liver cancer | 32 | 20 | 4.2 (4.0–4.4) | 7.7 (7.6–7.8) | 3,028 | 14,721 | 83.3% | |||

| Females | ||||||||||

| All causes of death | 1,019.3 (1,017.0–1,021.5) | 619.2 (618.2–620.3) | 840,805 | 1,374,354 | −39.3% | |||||

| Heart diseases | 1 | 1 | 404.4 (402.9–405.8) | 129.4 (128.9–129.9) | 317,341 | 299,563 | −68.0% | |||

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and allied conditions | 15 | 2 | 7.9 (7.7–8.1) | 38.2 (37.9–38.4) | 6,985 | 85,194 | 383.5% | |||

| Cerebrovascular diseases | 2 | 3 | 147.9 (147.0–148.8) | 36.6 (36.4–36.9) | 112,920 | 84,737 | −75.3% | |||

| Alzheimer’s | – | 4 | – | 34.7 (34.5–34.9) | – | 84,078 | – | |||

| Accidents and adverse effects | 3 | 5 | 39.2 (38.7–39.6) | 32.0 (31.7–32.2) | 35,658 | 60,212 | −18.4% | |||

| Lung and bronchus cancers | 10 | 6 | 12.2 (12.0–12.4) | 30.6 (30.4–30.9) | 11,323 | 67,155 | 150.8% | |||

| Breast cancer | 5 | 7 | 31.8 (31.4–32.2) | 19.9 (19.7–20.1) | 28,828 | 42,000 | −37.4% | |||

| Diabetes mellitus | 8 | 8 | 26.4 (26.0–26.7) | 17.1 (16.9–17.3) | 22,848 | 37,262 | −35.2% | |||

| Pneumonia and influenza | 4 | 9 | 38.4 (38.0–38.9) | 12.7 (12.5–12.8) | 30,489 | 29,114 | −66.9% | |||

| Colon and rectum cancers | 7 | 10 | 26.7 (26.4–27.1) | 11.4 (11.2–11.5) | 23,145 | 24,750 | −57.3% | |||

| Nephritis, nephrotic syndrome and nephrosis | 22 | 11 | 6.6 (6.5–6.8) | 11.1 (10.9–11.2) | 5,718 | 24,889 | 68.2% | |||

| Septicemia | 40 | 12 | 1.5 (1.4–1.5) | 9.7 (9.6–9.8) | 1,357 | 21,319 | 546.7% | |||

| Pancreatic cancer | 14 | 13 | 8.7 (8.5–8.9) | 9.6 (9.4–9.7) | 7,716 | 21,092 | 10.3% | |||

| Hypertension without heart disease | 25 | 14 | 5.2 (5.0–5.3) | 8.4 (8.3–8.5) | 4,088 | 19,556 | 61.5% | |||

| Symptoms, signs and ill-defined conditions | 11 | 15 | 12.0 (11.7–12.2) | 8.0 (7.9–8.1) | 10,385 | 17,352 | −33.3% | |||

| Chronic liver disease and cirrhosis | 12 | 16 | 11.4 (11.2–11.7) | 7.6 (7.5–7.8) | 10,485 | 15,291 | −33.3% | |||

| Ovarian cancer | 13 | 17 | 10.4 (10.2–10.6) | 6.6 (6.5–6.7) | 9,670 | 14,193 | −36.5% | |||

| Suicide and self-inflicted injury | 19 | 18 | 7.1 (6.9–7.3) | 6.1 (6.0–6.3) | 6,503 | 10,389 | −14.1% | |||

| Corpus and uterus cancers | 23 | 19 | 6.0 (5.9–6.2) | 5.0 (4.9–5.1) | 5,477 | 10,994 | −16.7% | |||

| Leukemia | 20 | 20 | 6.8 (6.7–7.0) | 4.6 (4.5–4.7) | 6,193 | 9,909 | −32.4% | |||

Rank is based on the age-adjusted mortality rate. Age-adjusted mortality rates are per 100,000 population and are age-adjusted to the United States standard population in 2000. Death count is the number of deaths. CI, confidence interval.

By contrast, in 2017, accidents and adverse effects had become the second leading cause of death among males and the fifth leading cause of death among females (Table 1). The age-adjusted mortality rate for accidents and adverse effects in males had risen by 37.8%, from a minimum of 49.2 (per 100,000 population) in 2000 to 67.8 (per 100,000 population) in 2017 (Table 1 and Figure 2A). Similarly, in females, the mortality rate for accidents and adverse effects had increased by 53.1%, from a minimum of 20.9 (per 100,000 population) in 1992 to 32.0 (per 100,000 population) in 2017 (Table 1 and Figure 2B). The age-adjusted mortality rate for suicide and self-inflicted injury in males rose by 26.6%, from a minimum of 17.7 (per 100,000 population) in 2000 to 22.4 (per 100,000 population) in 2017, and increased by 52.5% in females, from a minimum of 4.0 (per 100,000 population) in 1999 to 6.1 (per 100,000 population) in 2017 (Table 1 and Figure 2). Surprisingly, the Alzheimer’s disease mortality rate increased in males (Figure 2A) and females (Figure 2B) by 4,900.0% and 8575.0%, from 0.5 and 0.4 (per 100,000 population) in 1979 to 25.0 and 34.7 (per 100,000 population) in 2017, and was the seventh and fourth leading cause of death in 2017, respectively.

The male age-adjusted mortality rate for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and allied conditions dropped by 23.4%, from a peak of 59.0 (per 100,000 population) in 1999 to 45.2 (per 100,000 population) in 2017. However, this rate increased in females by 383.5%, from 7.9 (per 100,000 population) in 1969 to 38.2 (per 100,000 population) in 2017, with no downward trend (Table 1 and Figure 2A,2B). Although mortality due to lung and bronchus cancers in males dropped by 50.9%, from a peak of 90.6 (per 100,000 population) in 1990 to 44.5 (per 100,000 population) in 2017, and decreased by 26.4% in females, from a peak of 41.6 (per 100,000 population) in 2002 to 30.6 (per 100,000 population) in 2017, it remained the leading cause of cancer death for both sexes in 2017 (Table 1 and Figure 2A,2B). Malignant cancers of the lung and bronchus, prostate, and colon and rectum were the three leading causes of cancer death in males in 2017 (Table 1). The same trend was found in females, except that breast cancer replaced prostate cancer (Table 2).

Table 2

| All causes | Mortality rank | Age-adjusted mortality rate (95% CI) | Death count | Relative change in mortality (2017 vs. 1969) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1969 | 2017 | 1969 | 2017 | 1969 | 2017 | ||||

| White males | |||||||||

| All causes of death | 1,577.5 (1,574.0–1,580.9) | 865.0 (863.4–866.5) | 945,081 | 1,212,411 | −45.2% | ||||

| Heart diseases | 1 | 1 | 673.1 (670.8–675.4) | 208.7 (207.9–209.4) | 383,936 | 295,002 | −69.0% | ||

| Accidents and adverse effects | 3 | 2 | 89.6 (88.8–90.3) | 71.0 (70.6–71.5) | 68,005 | 91,794 | −20.8% | ||

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and allied conditions | 6 | 3 | 40.2 (39.7–40.7) | 47.4 (47.0–47.8) | 25,091 | 67,623 | 17.9% | ||

| Lung and bronchus cancers | 4 | 4 | 64.4 (63.8–65.1) | 44.7 (44.3–45.0) | 45,235 | 67,201 | −30.6% | ||

| Cerebrovascular diseases | 2 | 5 | 163.8 (162.6–165.1) | 36.4 (36.0–36.7) | 81,621 | 50,146 | −77.8% | ||

| Alzheimer’s | − | 6 | − | 25.9 (25.7–26.2) | − | 33,898 | − | ||

| Suicide and self-inflicted injury | 12 | 7 | 20.3 (20.0–20.7) | 25.2 (24.9–25.4) | 14,883 | 32,863 | 24.1% | ||

| Diabetes mellitus | 10 | 8 | 23.0 (22.6–23.4) | 25.0 (24.7–25.2) | 13,614 | 36,393 | 8.7% | ||

| Prostate cancer | 9 | 9 | 28.1 (27.6–28.6) | 17.8 (17.5–18.0) | 14,365 | 24,657 | −36.7% | ||

| Pneumonia and influenza | 5 | 10 | 58.7 (57.9–59.4) | 16.3 (16.1–16.6) | 31,484 | 22,454 | −72.2% | ||

| Colon and rectum cancers | 7 | 11 | 33.8 (33.3–34.3) | 15.6 (15.4–15.8) | 20,317 | 22,811 | −53.8% | ||

| Chronic liver disease and cirrhosis | 11 | 12 | 22.3 (22.0–22.7) | 15.4 (15.2–15.6) | 16,512 | 23,251 | −30.9% | ||

| Nephritis, nephrotic syndrome and nephrosis | 23 | 13 | 9.0 (8.7–9.2) | 14.5 (14.3–14.7) | 5,318 | 20,184 | 61.1% | ||

| Pancreatic cancer | 17 | 14 | 13.9 (13.6–14.2) | 13.0 (12.8–13.2) | 8,837 | 19,525 | −6.5% | ||

| Septicemia | 37 | 15 | 1.8 (1.7–2.0) | 11.2 (11.0–11.4) | 1,232 | 15,900 | 522.2% | ||

| Symptoms, signs and ill-defined conditions | 14 | 16 | 16.3 (16.0–16.7) | 9.3 (9.2–9.5) | 10,722 | 12,519 | −42.9% | ||

| Hypertension without heart disease | 25 | 17 | 6.6 (6.4–6.9) | 8.6 (8.4–8.7) | 3,288 | 12,050 | 30.3% | ||

| Leukemia | 18 | 17 | 11.7 (11.4–12.0) | 8.6 (8.4–8.8) | 7,640 | 12,096 | −26.5% | ||

| Urinary bladder cancer | 21 | 19 | 9.6 (9.3–9.9) | 7.7 (7.6–7.9) | 5,515 | 10,891 | −19.8% | ||

| Lymphoma | 19 | 20 | 9.7 (9.4–9.9) | 7.6 (7.4–7.7) | 6,725 | 10,812 | −21.6% | ||

| Black males | |||||||||

| All causes of death | 1,957.7 (1,945.5–1,969.9) | 1,058.3 (1,053.0–1,063.6) | 127,043 | 177,318 | −45.9% | ||||

| Heart diseases | 1 | 1 | 643.7 (636.3–651.1) | 259.8 (257.2–262.5) | 35,582 | 42,084 | −59.6% | ||

| Accidents and adverse effects | 3 | 2 | 127.5 (124.9–130.2) | 68.8 (67.6–70.0) | 11,322 | 14,197 | −46.0% | ||

| Cerebrovascular diseases | 2 | 3 | 225.5 (221.0–230.0) | 56.9 (55.6–58.1) | 11,954 | 8,670 | −74.8% | ||

| Lung and bronchus cancers | 6 | 4 | 73.2 (71.0–75.4) | 52.2 (51.1–53.4) | 4,914 | 8,825 | −28.7% | ||

| Diabetes mellitus | 11 | 5 | 31.2 (29.7–32.7) | 45.6 (44.5–46.7) | 1,902 | 7,611 | 46.2% | ||

| Homicide and legal intervention | 5 | 6 | 77.1 (75.2–79.0) | 38.5 (37.7–39.3) | 6,763 | 8,924 | −50.1% | ||

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and allied conditions | 14 | 7 | 26.0 (24.6–27.4) | 38.1 (37.0–39.1) | 1,629 | 5,692 | 46.5% | ||

| Prostate cancer | 8 | 8 | 50.0 (47.8–52.2) | 36.4 (35.3–37.4) | 2,405 | 5,065 | −27.2% | ||

| Nephritis, nephrotic syndrome and nephrosis | 16 | 9 | 24.6 (23.2–26.0) | 29.9 (29.0–30.9) | 1,506 | 4,591 | 21.5% | ||

| Alzheimer’s | − | 10 | − | 22.5 (21.6–23.4) | − | 2,502 | − | ||

| Colon and rectum cancers | 13 | 11 | 27.1 (25.7–28.6) | 22.3 (21.5–23.0) | 1,585 | 3,802 | −17.7% | ||

| Septicemia | 32 | 12 | 4.7 (4.1–5.3) | 19.4 (18.7–20.1) | 387 | 3,090 | 312.8% | ||

| Hypertension without heart disease | 17 | 13 | 17.0 (15.9–18.2) | 18.8 (18.0–19.5) | 1,018 | 2,926 | 10.6% | ||

| Pneumonia and influenza | 4 | 14 | 86.6 (84.0–89.2) | 18.2 (17.5–18.9) | 5,979 | 2,732 | −79.0% | ||

| Pancreatic cancer | 18 | 15 | 16.5 (15.4–17.6) | 14.9 (14.3–15.5) | 1,008 | 2,602 | −9.7% | ||

| Symptoms, signs and ill-defined conditions | 7 | 16 | 71.8 (69.5–74.2) | 12.7 (12.1–13.2) | 4,781 | 2,356 | −82.3% | ||

| Liver cancer | 30 | 17 | 6.9 (6.2–7.6) | 11.1 (10.6–11.6) | 439 | 2,257 | 60.9% | ||

| Suicide and self-inflicted injury | 21 | 18 | 10.0 (9.3–10.7) | 11.0 (10.5–11.4) | 804 | 2,421 | 10.0% | ||

| Chronic liver disease and cirrhosis | 9 | 19 | 36.2 (34.8–37.6) | 10.1 (9.6–10.5) | 2,632 | 2,106 | −72.1% | ||

| Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) | − | 20 | − | 9.5 (9.1–10.0) | − | 2,002 | − | ||

| Other males | |||||||||

| All causes of death | 1,100.7 (1,075.1–1,126.7) | 512.0 (507.4–516.7) | 8,395 | 49,291 | −53.5% | ||||

| Heart diseases | 1 | 1 | 341.3 (326.5–356.6) | 116.0 (113.8–118.3) | 2,211 | 10,768 | −66.0% | ||

| Accidents and adverse effects | 2 | 2 | 124.5 (117.2–132.0) | 32.0 (31.0–33.1) | 1,312 | 3,717 | −74.3% | ||

| Cerebrovascular diseases | 3 | 3 | 102.3 (94.0–111.0) | 31.7 (30.5–32.9) | 628 | 2,828 | −69.0% | ||

| Lung and bronchus cancers | 5 | 4 | 34.6 (30.2–39.4) | 27.5 |

244 | 2,668 | −20.5% | ||

| Diabetes mellitus | 8 | 5 | 25.0 (21.1–29.3) | 23.6 (22.6–24.6) | 166 | 2,297 | −5.6% | ||

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and allied conditions | 10 | 6 | 20.6 (17.2–24.6) | 19.7 (18.7–20.6) | 137 | 1,684 | −4.4% | ||

| Pneumonia and influenza | 4 | 7 | 53.1 (47.4–59.2) | 16.2 (15.3–17.1) | 387 | 1,371 | −69.5% | ||

| Alzheimer’s | – | 8 | – | 12.3 (11.5–13.1) | – | 924 | – | ||

| Suicide and self-inflicted injury | 12 | 9 | 17.4 (14.6–20.6) | 11.7 (11.1–12.3) | 167 | 1,495 | −32.8% | ||

| Colon and rectum cancers | 11 | 10 | 20.1 (16.8–23.9) | 11.6 (10.9–12.3) | 142 | 1,184 | −42.3% | ||

| Nephritis, nephrotic syndrome and nephrosis | 21 | 11 | 8.8 (6.8–11.3) | 10.7 (10.0–11.4) | 70 | 969 | 21.6% | ||

| Liver cancer | 17 | 12 | 10.4 (8.1–13.2) | 10.1 (9.4–10.7) | 75 | 1,076 | −2.9% | ||

| Chronic liver disease and cirrhosis | 6 | 13 | 27.1 (23.6–31.0) | 9.3 (8.8–9.9) | 228 | 1,093 | −65.7% | ||

| Prostate cancer | 16 | 14 | 10.9 (8.2–14.0) | 9.0 (8.4–9.7) | 64 | 764 | −17.4% | ||

| Hypertension without heart disease | 28 | 15 | 5.0 (3.3–7.1) | 8.7 (8.1–9.3) | 31 | 766 | 74.0% | ||

| Pancreatic cancer | 15 | 16 | 13.5 (10.7–16.8) | 7.9 (7.4–8.5) | 86 | 792 | −41.5% | ||

| Septicemia | 32 | 17 | 3.2 (2.1–4.7) | 6.5 (5.9–7.0) | 31 | 613 | 103.1% | ||

| Stomach cancer | 9 | 18 | 23.7 (19.9–28.0) | 5.9 (5.4–6.4) | 152 | 578 | −75.1% | ||

| Symptoms, signs and ill-defined conditions | 7 | 19 | 26.8 (23.0–31.1) | 4.9 (4.4–5.3) | 214 | 505 | −81.7% | ||

| Leukemia | 22 | 19 | 6.8 (5.0–8.9) | 4.9 (4.5–5.4) | 62 | 472 | −27.9% | ||

Rank is based on the age-adjusted mortality rate. Age-adjusted mortality rates are per 100,000 population and are age-adjusted to the United States standard population in 2000. Other denotes other races and ethnicities, including American Indian/AK Native, Asian/Pacific Islander. Death count is the number of deaths. CI, confidence interval.

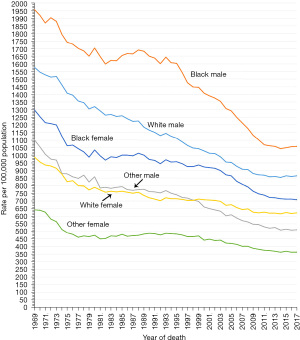

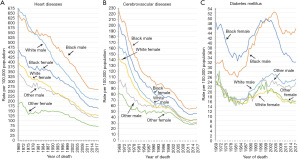

Trends in disease mortality rates by race and ethnicity

The age-adjusted mortality rate changes in different races and ethnicities from 1969 to 2017 were also analyzed (Tables 2,3). The mortality rates of all causes of death were higher for blacks than whites, irrespective of sex, from 1969 to 2017 (Figure 3). From 1979 to 2017, blacks had higher mortality rates than whites in three major chronic diseases (heart diseases, cerebrovascular diseases, and diabetes mellitus) for both sexes (Figure 4A-4C).

Table 3

| All causes | Mortality rank | Age-adjusted mortality rate (95% CI) | Death count | Relative change in mortality (2017 vs. 1969) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1969 | 2017 | 1969 | 2017 | 1969 | 2017 | ||||

| White females | |||||||||

| All causes of death | 988.7 (986.4–991.0) | 622.2 (621.0–623.3) | 738,063 | 1,165,866 | −37.1% | ||||

| Heart diseases | 1 | 1 | 398.5 (397.0–400.0) | 128.0 (127.5–128.5) | 285,601 | 253,605 | −67.9% | ||

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and allied conditions | 15 | 2 | 7.8 (7.6–8.0) | 41.5 (41.2–41.8) | 6,342 | 78,122 | 432.1% | ||

| Alzheimer’s | – | 3 | – | 36.1 (35.8–36.4) | – | 75,411 | – | ||

| Cerebrovascular diseases | 2 | 4 | 142.9 (142.0–143.8) | 35.6 (35.3–35.8) | 99,170 | 70,644 | −75.1% | ||

| Accidents and adverse effects | 3 | 5 | 38.2 (37.8–38.7) | 34.4 (34.1–34.7) | 30,867 | 52,023 | −9.9% | ||

| Lung and bronchus cancers | 10 | 6 | 12.2 (11.9–12.4) | 31.9 (31.7–32.2) | 10,267 | 58,371 | 161.5% | ||

| Breast cancer | 5 | 7 | 32.0 (31.6–32.4) | 19.4 (19.2–19.6) | 26,333 | 33,988 | −39.4% | ||

| Diabetes mellitus | 8 | 8 | 24.3 (24.0–24.7) | 15.2 (15.0–15.4) | 19,049 | 27,904 | −37.4% | ||

| Pneumonia and influenza | 4 | 9 | 36.9 (36.5–37.4) | 12.7 (12.5–12.9) | 26,139 | 24,823 | −65.6% | ||

| Colon and rectum cancers | 7 | 10 | 26.8 (26.5–27.2) | 11.2 (11.1–11.4) | 21,233 | 20,332 | −58.2% | ||

| Nephritis, nephrotic syndrome and nephrosis | 24 | 11 | 5.6 (5.5–5.8) | 9.9 (9.7–10.0) | 4,347 | 18,921 | 76.8% | ||

| Pancreatic cancer | 14 | 12 | 8.6 (8.4–8.9) | 9.5 (9.3–9.6) | 7,005 | 17,468 | 10.5% | ||

| Septicemia | 39 | 13 | 1.3 (1.2–1.3) | 9.3 (9.1–9.4) | 1,042 | 17,169 | 615.4% | ||

| Chronic liver disease and cirrhosis | 12 | 14 | 10.3 (10.1–10.6) | 8.2 (8.1–8.3) | 8,634 | 13,275 | −20.4% | ||

| Symptoms, signs and ill-defined conditions | 13 | 15 | 8.7 (8.5–8.9) | 8.0 (7.8–8.1) | 6,658 | 14,674 | −8.0% | ||

| Hypertension without heart disease | 26 | 16 | 4.4 (4.3–4.6) | 7.6 (7.4–7.7) | 3,131 | 15,196 | 72.7% | ||

| Suicide and self-inflicted injury | 16 | 17 | 7.6 (7.4–7.8) | 6.9 (6.8–7.1) | 6,148 | 9,151 | −9.2% | ||

| Ovarian cancer | 11 | 18 | 10.6 (10.4–10.8) | 6.8 (6.7–7.0) | 8,956 | 12,198 | −35.8% | ||

| Leukemia | 19 | 19 | 7.0 (6.8–7.2) | 4.8 (4.7–4.9) | 5,723 | 8,622 | −31.4% | ||

| Corpus and uterine cancers | 23 | 20 | 5.7 (5.5–5.9) | 4.6 (4.5–4.7) | 4,705 | 8,394 | −19.3% | ||

| Black females | |||||||||

| All causes of death | 1,299.5 (1,290.7–1,308.4) | 708.8 (705.3–712.3) | 98,316 | 163,305 | −45.5% | ||||

| Heart diseases | 1 | 1 | 463.7 (458.2–469.3) | 162.6 (160.9–164.3) | 30,788 | 37,231 | −64.9% | ||

| Cerebrovascular diseases | 2 | 2 | 202.9 (199.2–206.6) | 47.2 (46.3–48.2) | 13,311 | 10,633 | −76.7% | ||

| Diabetes mellitus | 3 | 3 | 48.3 (46.6–49.9) | 32.0 (31.2–32.7) | 3,649 | 7,378 | −33.7% | ||

| Alzheimer’s | – | 4 | – | 30.5 (29.8–31.3) | – | 6,582 | – | ||

| Lung and bronchus cancers | 16 | 5 | 12.5 (11.7–13.3) | 28.2 (27.5–28.9) | 990 | 6,713 | 125.6% | ||

| Breast cancer | 7 | 6 | 30.3 (29.1–31.6) | 26.9 (26.2–27.6) | 2,415 | 6,427 | −11.2% | ||

| Accidents and adverse effects | 6 | 7 | 44.2 (42.7–45.7) | 25.9 (25.2–26.6) | 4,368 | 6,136 | −41.4% | ||

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and allied conditions | 24 | 8 | 7.1 (6.5–7.7) | 24.5 (23.9–25.2) | 596 | 5,671 | 245.1% | ||

| Nephritis, nephrotic syndrome and nephrosis | 13 | 9 | 16.8 (15.8–17.8) | 22.0 (21.3–22.6) | 1,320 | 5,018 | 31.0% | ||

| Septicemia | 33 | 10 | 3.1 (2.7–3.5) | 15.4 (14.9–15.9) | 297 | 3,551 | 396.8% | ||

| Hypertension without heart disease | 15 | 11 | 12.6 (11.8–13.5) | 15.1 (14.6–15.6) | 942 | 3,434 | 19.8% | ||

| Colon and rectum cancers | 9 | 12 | 25.4 (24.1–26.6) | 14.5 (14.0–15.0) | 1,832 | 3,407 | −42.9% | ||

| Pneumonia and influenza | 4 | 13 | 48.2 (46.6–49.9) | 12.9 (12.4–13.4) | 4,117 | 2,926 | −73.2% | ||

| Pancreatic cancer | 19 | 14 | 9.1 (8.4–9.8) | 11.8 (11.4–12.3) | 680 | 2,781 | 29.7% | ||

| Symptoms, signs and ill-defined conditions | 5 | 15 | 46.6 (44.9–48.3) | 9.8 (9.4–10.2) | 3,594 | 2,246 | −79.0% | ||

| Corpus and uterine cancers | 17 | 16 | 9.7 (9.0–10.5) | 8.8 (8.4–9.2) | 748 | 2,152 | −9.3% | ||

| Certain conditions originating in the perinatal period | 8 | 17 | 26.0 (25.2–26.8) | 6.9 (6.6–7.3) | 4,461 | 1,645 | −73.5% | ||

| Ovarian cancer | 21 | 18 | 8.1 (7.5–8.8) | 5.8 (5.5–6.2) | 679 | 1,405 | −28.4% | ||

| Homicide and legal intervention | 14 | 19 | 14.2 (13.5–15.0) | 5.4 (5.1–5.7) | 1,457 | 1,301 | −62.0% | ||

| Chronic liver disease and cirrhosis | 11 | 20 | 19.5 (18.6–20.5) | 5.0 (4.7–5.3) | 1,676 | 1,245 | −74.4% | ||

| Myeloma | 32 | 20 | 3.4 (3.0–3.9) | 5.0 (4.7–5.3) | 261 | 1,132 | 47.1% | ||

| Other females | |||||||||

| All causes of death | 643.0 (622.0–664.5) | 363.9 (360.5–367.3) | 4,426 | 45,183 | −43.4% | ||||

| Heart diseases | 1 | 1 | 182.6 (170.6–195.2) | 71.7 (70.1–73.2) | 952 | 8,727 | −60.7% | ||

| Cerebrovascular diseases | 2 | 2 | 82.6 (74.6–91.0) | 28.6 (27.7–29.6) | 439 | 3,460 | −65.4% | ||

| Alzheimer’s | – | 3 | – | 17.6 (16.8–18.3) | – | 2,085 | – | ||

| Lung and bronchus cancers | 12 | 4 | 10.3 (7.8–13.2) | 16.2 (15.5–17.0) | 66 | 2,071 | 57.3% | ||

| Diabetes mellitus | 5 | 5 | 24.4 (20.5–28.8) | 16.1 (15.4–16.8) | 150 | 1,980 | −34.0% | ||

| Accidents and adverse effects | 3 | 6 | 40.6 (36.3–45.3) | 15.8 (15.1–16.5) | 423 | 2,053 | −61.1% | ||

| Breast cancer | 10 | 7 | 10.7 (8.4–13.4) | 11.8 (11.2–12.4) | 80 | 1,585 | 10.3% | ||

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and allied conditions | 17 | 8 | 6.9 (4.9–9.3) | 11.6 (11.0–12.2) | 47 | 1,401 | 68.1% | ||

| Pneumonia and influenza | 4 | 9 | 31.6 (27.0–36.7) | 11.2 (10.6–11.8) | 233 | 1,365 | −64.6% | ||

| Colon and rectum cancers | 9 | 10 | 13.4 (10.5–16.7) | 7.9 (7.4–8.4) | 80 | 1,011 | −41.0% | ||

| Nephritis, nephrotic syndrome and nephrosis | 15 | 11 | 7.0 (5.1–9.4) | 7.8 (7.3–8.4) | 51 | 950 | 11.4% | ||

| Hypertension without heart disease | 33 | 12 | 2.5 (1.3–4.3) | 7.7 (7.2–8.2) | 15 | 926 | 208.0% | ||

| Pancreatic cancer | 20 | 13 | 5.6 (3.7–7.9) | 6.7 (6.3–7.2) | 31 | 843 | 19.6% | ||

| Chronic liver disease and cirrhosis | 6 | 14 | 19.8 (16.8–23.1) | 5.7 (5.3–6.1) | 175 | 771 | −71.2% | ||

| Septicemia | 35 | 15 | 1.5 (0.8–2.7) | 4.8 (4.4–5.2) | 18 | 599 | 220.0% | ||

| Suicide and self-inflicted injury | 13 | 16 | 7.3 (5.5–9.4) | 4.4 (4.0–4.7) | 69 | 597 | −39.7% | ||

| Ovarian cancer | 21 | 16 | 4.9 (3.4–6.9) | 4.4 (4.0–4.7) | 35 | 590 | −10.2% | ||

| Stomach cancer | 8 | 18 | 14.0 (11.1–17.4) | 3.8 (3.5–4.2) | 86 | 488 | −72.9% | ||

| Liver cancer | 23 | 19 | 4.2 (2.6–6.2) | 3.6 (3.3–3.9) | 24 | 447 | −14.3% | ||

| Symptoms, signs and ill-defined conditions | 7 | 20 | 17.6 (14.2–21.4) | 3.5 (3.2–3.9) | 133 | 432 | −80.1% | ||

Rank is based on the age-adjusted mortality rate. Age-adjusted mortality rates are per 100,000 population and are age-adjusted to the United States standard population in 2000. Other denotes other races and ethnicities, including American Indian/AK Native, Asian/Pacific Islander. Death count is the number of deaths. CI, confidence interval.

The top three causes of death in 2017 in white males were heart diseases, accidents and adverse effects, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and allied conditions (Table 2 and Figure S1A). The top three causes of death in 2017 in black males and males of other races and ethnicities were heart diseases, accidents and adverse effects, and cerebrovascular diseases (Table 2 and Figure S1B,S1C). The top three causes of death in 2017 in white females were heart diseases, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and allied conditions, and Alzheimer’s (Table 3 and Figure S2A). The top three causes of death in 2017 in black females were heart diseases, cerebrovascular diseases, and diabetes mellitus (Table 3 and Figure S2B). The top three causes of death in 2017 in females of other races and ethnicities were heart diseases, cerebrovascular diseases, and Alzheimer’s (Table 3 and Figure S2C).

Trends in disease mortality rates by age intervals

In addition, the age-adjusted mortality rate changes in different age intervals from 1969 to 2017 were also analyzed (Tables S1,S2). Mortality rates among males were higher than those among females across all age intervals from 1969 to 2017 (Figure 5). The top three causes of death in males aged between birth and 39 years in 2017 were accidents and adverse effects, suicide and self-inflicted injury, and homicide and legal intervention (Table S1 and Figure S3A), in males aged 40–49 years in 2017 were accidents and adverse effects, heart diseases, and suicide and self-inflicted injury (Table S1 and Figure S3B), in males aged 50–59 years in 2017 were heart diseases, accidents and adverse effects, and lung and bronchus cancers (Table S1 and Figure S3C), in males aged 60–69 years in 2017 were heart diseases, lung and bronchus cancers, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and allied conditions (Table S1 and Figure S3D), and in males aged ≥70 years in 2017 were heart diseases, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and allied conditions, and cerebrovascular diseases (Table S1 and Figure S3E). The top three causes of death in females aged between birth and 39 years in 2017 were accidents and adverse effects, certain conditions originating in the perinatal period, and suicide and self-inflicted injury (Table S2 and Figure S4A), in females aged 40–49 years in 2017 were accidents and adverse effects, heart diseases, and breast cancer (Table S2 and Figure S4B), in females aged 50–59 years in 2017 were heart diseases, accidents and adverse effects, and lung and bronchus cancers (Table S2 and Figure S4C), in females aged 60–69 years in 2017 were heart diseases, lung and bronchus cancers, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and allied conditions (Table S2 and Figure S4D), in females aged ≥70 years in 2017 were heart diseases, Alzheimer’s, and cerebrovascular diseases (Table S2 and Figure S4E).

Discussion

A total of 109,836,044 deaths were recorded in the U.S. from 1969 to 2017. This represents substantial data that can truly reflect the real causes of death among Americans. From 1969 to 2017, health outcomes underwent dramatic changes across the U.S. (6). In the past 50 years, the rapid development of industrial technology has presented new problems. In 2017, accidents and adverse effects became the second leading cause of death among males, and the fifth leading cause of death among females (Figure 2). The mortality rate per 100,000 population for accidents and adverse effects in males rose by 37.8%, from a minimum of 49.2 in 2000 to 67.8 in 2017, and increased by 53.1% in females, from a minimum of 20.9 in 1992 to 32.0 in 2017 (Figure 2). The main type of accidents and adverse effects were traffic accidents. The rise in the mortality rate of accidents is debatable, but it is speculated to be related to the use of smart phones (7,8). Suicide rates have also risen in the U.S. (9,10). The mortality rate per 100,000 population for suicide and self-inflicted injury in males rose by 26.6%, from a minimum of 17.7 in 2000 to 22.4 in 2017, and increased by 52.5% in females, from a minimum of 4.0 in 1999 to 6.1 in 2017 (Table 1 and Figure 2). In 2017, suicide and self-inflicted injury was the second-leading cause of death in males between birth and 39 years, and the third-leading causes of death in females of the same age range (Figures S3A,S4A). Speculations explaining this rise in suicide rates have been proposed, but the exact causes for the increase remain unknown (9,11). Improving social connectedness, civic opportunities, and health insurance coverage, as well as limiting access to lethal means, have the potential to reduce suicide rates (12). In addition, with the aging of the U.S. population, Alzheimer’s is becoming an increasingly common cause of death. From 1979 to 2017, the mortality rate per 100,000 population for Alzheimer’s increased by 4,900.0% (0.5 to 25.0) in males and 8,575.0% (0.4 to 34.7) in females (Figure 2). Alzheimer’s is the only cause of death among the top 10 that cannot be prevented, cured, or even slowed (13). The rapid increase in the elderly population is responsible for the rapid increase in the mortality rate for Alzheimer’s in the U.S. (14,15).

The advancement of medicine in the past half-century was also evident. The overall annual mortality rate of the U.S. population declined continuously from 1969 to 2017, and the overall life expectancy in the U.S. increased from 70.5 years in 1969 to 78.6 years in 2017 (16). The overall mortality rate in males per 100,000 population fell by 46.1%, from 1,610.0 in 1969 to 867.2 in 2017, and likewise, decreased by 39.3% in females, from 1,019.3 in 1969 to 619.2 in 2017 (Table 1 and Figure 1). This decline in overall mortality was mainly due to a reduction in mortality caused by heart and cerebrovascular diseases. From 1969 to 2017, the mortality rates for heart and cerebrovascular diseases have continually declined (Figure 2). Although it has remained the leading cause of death among both males and females in the U.S., the mortality rate per 100,000 population for heart diseases in males dropped by 68.6%, from 668.2 in 1969 to 209.6 in 2017, and fell by 68.0% in females, from 404.4 in 1969 to 129.4 in 2017 (Figure 2A,2B). Similarly, from 1969 to 2017, the mortality rate per 100,000 population for cerebrovascular diseases decreased by 77.3% (168.4 to 38.2) in males and 75.3% (147.9 to 36.6) in females (Figure 2A,2B). The decrease in mortality rates due to heart and cerebrovascular diseases observed in this report across the entire U.S. population has been well documented (17,18). This half-century decline in heart and cerebrovascular diseases mortality is a “milestone of progress” in medicine, and is the result of improved levels of treatment, advances in preventive measures, national policy support, among others (17-19). However, this downward trend in heart and cerebrovascular disease mortality has slowed, and even reversed, among certain demographics after 2012 (20). Further concerns exist with regards to cardiovascular and cerebrovascular drug innovations, quality of care, and healthcare costs (20). As the population ages, there is an urgent need for action to improve innovation in, treatment of, and payment for cardiovascular and cerebrovascular health (18,20). At present, China’s heart and cerebrovascular diseases mortality is still showing an upward trend. Some measures taken by the U.S. to reduce heart and cerebrovascular diseases mortality are worthy of our reference.

The mortality rate for all malignant cancers has also declined in the past 50 years (2). Among the 10 leading causes of death in 2016, there were two cancers in men (cancers of the lung and bronchus, and prostate), and similarly, three cancers in women (cancers of the lung and bronchus, breast, and colon and rectum). The mortality rates of these cancers for both sexes have continued to decline after 2002. Although the mortality rate for lung and bronchus cancers in males dropped by 50.9% from 1990 to 2017, and decreased in females by 26.4% from 2002 to 2017, it has remained the leading cause of cancer death among both males and females in 2017 (Figure 2A,2B). The 5-year relative survival rate for all cancers combined, diagnosed in 2008–2014, was 67% in whites and 62% in blacks, but only 19% for lung and bronchus cancer (2). Therefore, low-dose computed tomographic screening needs to be strengthened for earlier diagnosis of lung cancer, which could significantly reduce mortality (21).

In addition, there are marked sex and race disparities in overall mortality. From 1969 to 2017, the mortality rate of all causes of death was higher for males than females (Figure 1), and in blacks than whites for both sexes (Figure 3). Throughout the world, women tend to live longer than men. Although biological, behavioral, and environmental factors are known contributory factors, the relative contribution of each of these factors remains unclear (22,23). Also, overall mortality varied considerably between racial and ethnic groups. Blacks had significantly lower educational attainment and homeownership and almost twice the proportion of households below the poverty level compared with whites, over a life span (24). These trends might help to explain the disparities in mortality attributed to chronic disease-related behaviors, health-related quality of life, and health care utilization (2,24). This study showed that the mortality rates of heart diseases, cerebrovascular diseases, and diabetes were all higher in blacks than in whites for both sexes (Figure 4). Universal and targeted interventions are needed to reduce black-white health disparities over a life span. Finally, it is not surprising that the causes of death among different age intervals also exhibit distinct characteristics. In 2017, the leading cause of death for both males and females aged between birth and 49 years was accidents and adverse effects, and heart diseases in those aged ≥50 years (Figures S3,S4). Depending on the age characteristics of the causes of death, targeted interventions for disease prevention and control, according to the different age intervals, would produce better health outcomes.

Limitations

A strength of our study is the use of nationwide, high-quality, population-based data on mortality for all causes of death from the SEER database. However, our study has several limitations that should be noted. Firstly, although the SEER database includes large and accurate mortality data, the data for non-fatal outcomes is lacking. Secondly, due to the nearly 50-year time span, the diagnostic technologies and standards for certain diseases might have changed, thereby potentially affecting the time trends of these diseases. Thirdly, the SEER database only contains data on people within the U.S. and does not represent changes in mortality worldwide. Therefore, it is necessary to establish a similar database in China, which will represent 1.4 billion people.

Conclusions

The continuous decline in the overall mortality rate from 1969 to 2017 has resulted in an overall decrease in the mortality rate of 46.1% in males and 39.3% in females. This decline in overall mortality is mainly due to a corresponding decrease in mortality caused by heart diseases and cerebrovascular diseases. From 1969 to 2017, the mortality rates of all causes of death were higher in males than females, and in blacks than whites for both sexes. From 1979 to 2017, the mortality rates of heart diseases, cerebrovascular diseases, and diabetes were all higher in blacks than in whites for both sexes. Our results provide important evidence for health policy development and interventions. These findings can be used by governments at the national level to identify major health problems and facilitate priority-setting. In addition, the time trends of population mortality rates from 1969 to 2017 can be used to help guide appropriate health policies in other countries throughout the world.

Acknowledgments

Funding: This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China, China (Grant number 31700690); and the Natural Science Foundation of Zhejiang Province, China (Grant number LQ18H180002).

Footnote

Reporting Checklist: The authors have completed the STROBE reporting checklist. Available at https://dx.doi.org/10.21037/apm-21-2835

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at https://dx.doi.org/10.21037/apm-21-2835). The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (as revised in 2013).

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- Zhou M, Wang H, Zeng X, et al. Mortality, morbidity, and risk factors in China and its provinces, 1990-2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet 2019;394:1145-58. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2019. CA Cancer J Clin 2019;69:7-34. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lu T, Yang X, Huang Y, et al. Trends in the incidence, treatment, and survival of patients with lung cancer in the last four decades. Cancer Manag Res 2019;11:943-53. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Houston KA, Henley SJ, Li J, et al. Patterns in lung cancer incidence rates and trends by histologic type in the United States, 2004-2009. Lung Cancer 2014;86:22-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Jemal A, Miller KD, Ma J, et al. Higher Lung Cancer Incidence in Young Women Than Young Men in the United States. N Engl J Med 2018;378:1999-2009. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Weir HK, Anderson RN, Coleman King SM, et al. Heart Disease and Cancer Deaths - Trends and Projections in the United States, 1969-2020. Prev Chronic Dis 2016;13:E157 [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lennon A, Oviedo-Trespalacios O, Matthews S. Pedestrian self-reported use of smart phones: Positive attitudes and high exposure influence intentions to cross the road while distracted. Accid Anal Prev 2017;98:338-47. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Caird JK, Simmons SM, Wiley K, et al. Does Talking on a Cell Phone, With a Passenger, or Dialing Affect Driving Performance? An Updated Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Experimental Studies. Hum Factors 2018;60:101-33. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Stanley B, Mann JJ. The Need for Innovation in Health Care Systems to Improve Suicide Prevention. JAMA Psychiatry 2020;77:96-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Sy KTL, Shaman J, Kandula S, et al. Spatiotemporal clustering of suicides in the US from 1999 to 2016: a spatial epidemiological approach. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 2019;54:1471-82. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- O'Rourke MC, Jamil RT, Siddiqui W. Suicide Screening and Prevention. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2021.

- Steelesmith DL, Fontanella CA, Campo JV, et al. Contextual Factors Associated With County-Level Suicide Rates in the United States, 1999 to 2016. JAMA Netw Open 2019;2:e1910936 [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Zissimopoulos JM, Tysinger BC, St Clair PA, et al. The Impact of Changes in Population Health and Mortality on Future Prevalence of Alzheimer's Disease and Other Dementias in the United States. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci 2018;73:S38-47. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Taylor CA, Greenlund SF, McGuire LC, et al. Deaths from Alzheimer's Disease - United States, 1999-2014. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2017;66:521-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kramarow EA, Tejada-Vera B. Dementia Mortality in the United States, 2000-2017. Natl Vital Stat Rep 2019;68:1-29. [PubMed]

- Arias E, Xu J, Kochanek KD. United States Life Tables, 2016. Natl Vital Stat Rep 2019;68:1-66. [PubMed]

- Van Dyke M, Greer S, Odom E, et al. Heart Disease Death Rates Among Blacks and Whites Aged ≥35 Years - United States, 1968-2015. MMWR Surveill Summ 2018;67:1-11. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Benjamin EJ, Muntner P, Alonso A, et al. Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics-2019 Update: A Report From the American Heart Association. Circulation 2019;139:e56-e528. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Roth GA, Dwyer-Lindgren L, Bertozzi-Villa A, et al. Trends and Patterns of Geographic Variation in Cardiovascular Mortality Among US Counties, 1980-2014. JAMA 2017;317:1976-92. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- McClellan M, Brown N, Califf RM, et al. Call to Action: Urgent Challenges in Cardiovascular Disease: A Presidential Advisory From the American Heart Association. Circulation 2019;139:e44-54. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- National Lung Screening Trial Research Team. Reduced lung-cancer mortality with low-dose computed tomographic screening. N Engl J Med 2011;365:395-409. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Crimmins EM, Shim H, Zhang YS, et al. Differences between Men and Women in Mortality and the Health Dimensions of the Morbidity Process. Clin Chem 2019;65:135-45. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Oksuzyan A, Juel K, Vaupel JW, et al. Men: good health and high mortality. Sex differences in health and aging. Aging Clin Exp Res 2008;20:91-102. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Cunningham TJ, Croft JB, Liu Y, et al. Vital Signs: Racial Disparities in Age-Specific Mortality Among Blacks or African Americans - United States, 1999-2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2017;66:444-56. [Crossref] [PubMed]