Long-term effects of immunosuppression treatment on IgA nephropathy: a systematic review and meta-analysis

Introduction

Immunoglobulin A (IgA) nephropathy is a primary glomerular disease formed due to the deposition of IgA immune complexes in the glomerular mesangial area, it could cause capillary and proliferative lesions in the glomeruli that manifest as hematuria or proteinuria, which may eventually lead to end-stage kidney disease (ESKD) (1). At present, it is widely considered that the glycosylation of IgA1 molecule causes its own aggregation, forms immune complexes, deposits in the kidney, induces mesangial cell proliferation and inflammatory reaction, and finally forms IgA nephropathy (2). Although there is a better understanding of the pathogenic mechanism of IgA nephropathy, still there is no fixed treatment for it, different treatment schemes should be given according to different symptoms of patients in order to retain renal function and slow down the progress of the disease, for example, Tripterygium wilfordii glycoside, emodin and angiotensin II receptor block (ARB) triple therapy can be given for patients with proteinuria, and patients with vascular inflammation can be given immunosuppressive agent therapy (2). Despite IgA nephropathy is an immune complex-mediated glomerulonephritis, the efficacy of immunosuppression in the treatment remains uncertain (3). Among the immunosuppressive therapies for IgA nephropathy, corticosteroids, cyclophosphamide, azathioprine, and mycophenolate mofetil (MMF) are the most common therapeutic agents (4). A meta-analysis (5) has systematically evaluated immunosuppressive therapy for IgA nephropathy and showed it has a significant effect on reducing renal injury caused by proliferative IgA nephropathy, but these meta-analyses focused on the short-term efficacy of immunosuppressive drugs and did not evaluate the long-term efficacy of these drugs. Another meta-analysis conducted by Natale et al. (6) has reported the long-term efficacy of immunosuppressive agents but it included quasi-randomised studies and risk of bias was high, the quality of the evidence was low. In this study, we included randomised controlled trials with an observation period >3 years to investigate the long-term effects of immunosuppressive drugs on IgA nephropathy.

We present the following article in accordance with the PRISMA reporting checklist (available at https://dx.doi.org/10.21037/apm-21-2883).

Methods

Criteria for inclusion in the meta-analysis

Literature type

Only randomized controlled trials (RCTs), including single-center and multi-center trials, were included in this study, and the articles were limited to English-language publications. Controlled clinical trials or quasi-RCTs were excluded due to possible allocation concealment problems.

Type of participants

All the participants had a clinicopathological diagnosis of IgA nephropathy, regardless of age, nationality, or region, and had an estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) value between 20–120 mL/min/1.73 m2 at the time of enrollment. Patients who were corticosteroid-resistant and could not be treated with systemic immunization were excluded from the study.

Description of interventions

The included studies all included an immunosuppressive agent treatment group (of patients treated with glucocorticoids, cyclophosphamide, azathioprine, or MMF), either as single agents or in combination, and a control group treated with a placebo or conventional supportive care only.

Outcome indicators

The main outcome indicator in the study was the renal survival rate.

The renal survivals should be those patients who didn’t die from renal diseases in the end, and those who didn’t develop ESKD diseases or had an eGFR decreasing by 40% comparing to the baseline.

The follow-up time of each study had to be >3 years.

Search strategy and literature identification

Search of mainstream databases

The following databases were searched: MEDLINE (1946 to August 2021), EMBASE (2000 to August 2021), PubMed (2000 to August 2021), and Cochrane library (2000 to August 2021). A quick search was performed with keywords. The input keywords were: (IgA nephropathy/IGAN) OR (long term) OR (end-stage renal failure/end-stage renal disease).

Searches of other sources

Google Scholar and ClinicalTrials.gov were also searched as other sources.

Literature screening and data extraction

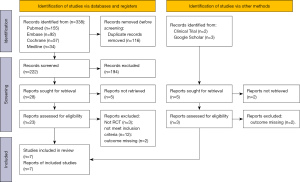

Two researchers independently screened the included studies and excluded duplicate articles and articles that did not obviously meet the exclusion and inclusion criteria based on a reading of the titles and abstracts. If there was a conflict of opinion between the two researchers, a 3rd researcher was consulted to resolve the difference of opinion. The selection flow chart of the literature followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) flow diagram.

The two researchers independently extracted the following data:

- Basic information about the article, including the title, author, mailing address, name of publication, publication time, and funding;

- Basic characteristics about the study, including the patient number, number of groups, and number of patients for each group;

- Basic characteristics about participants, including the age of participants, gender ratio, smoking, body mass index, blood pressure, urinary protein excretion rate, serum creatinine level, eGFR, and total cholesterol level;

- Characteristics of intervention, including the different intervention methods used in the experimental group and the control group; and

- Outcome assessment, including the follow-up time, number of deaths, number of ESKD cases, and number of adverse reactions.

Literature bias and evaluation analysis

The risk of bias for the RCTs was assessed according to the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions for the 6 domains including selection bias, performance bias, detection bias, attrition bias, reporting bias, and other bias each domain would be rated as high, low, or unclear for one study. If the study was rated ‘high’ for the domain, we judge the study be at high risk of bias for the domain.

Statistical analysis

The following statistical methods were used: (I) effect measurement: the binary variables (renal survival and adverse effects) were assessed using the risk ratio (RR) and 95% confidence interval (CI). The studies reporting these variables were included in the analysis. (II) Handling of data loss: if an article did not include the data, the original author of the article was contacted to obtain the data. If the data could not be obtained, the article was excluded. (III) Heterogeneity testing: an I2 analysis and Q test were used for the analysis. An I2>50% or P<0.1 indicated statistically significant heterogeneity. A fixed-inverse variance model was used for the analysis, or a random I–V model was otherwise used for the analysis. (IV) Analysis of publication bias: funnel plots were used to present the publication bias results. (V) Data synthesis analysis: Stata 16.0 was used as the analysis tool for this study, and forest plots were used to present the results. (VI) Heterogeneity investigation: a subgroup analysis was conducted to investigate heterogeneity. (VII) Sensitivity analysis: sensitivity analyses were performed using the sensitivity analysis tool in Stata 16.0.

Results

Literature search results and screening process

Figure 1 shows the results of the literature search and the screening process.

Basic characteristics of included articles

Seven articles comprising a total of 744 patients were included in the study. Most articles included a small amount of patient data, with sample sizes ranging from 34 to 260. All the studies compared immunosuppressive therapy to a placebo. All the articles recorded patients that dropped out of the study at each stage of the follow-up time with details. The basic characteristics of the articles are set out in Table 1.

Table 1

| Author | Group | Number of subjects | Age, mean (SD) (years) | EGFR, mean (SD) (mL/min/1.73 m2) | SCR, mean (SD) (mg/dL) | Intervention methods | Follow-up time (years) | Renal survival, n |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lv J 2017, (7) | E | 134 | 38.6 (11.5) | 60.0 (24.8) | 1.5 (0.6) | Oral methylprednisolone (0.6–0.8 mg/kg/d; maximum, 48 mg/d) | 5 | 126/134 |

| C | 126 | 38.6 (10.7) | 58.6 (25.2) | 1.6 (0.6) | Placebo | 106/126 | ||

| Kamei K 2011, (8) | E | 40 | 12.2 (3.0) | 144 (52.0) | – | Combination therapy: prednisolone + azathioprine + basic therapy for 24 months | 10 | 36/40 |

| C | 34 | 11.6 (2.3) | 152 (47.0) | – | Basic therapy for 24 months | 24/34 | ||

| Rauen T 2020, (9) | E | 77 | – | – | – | Immunosuppressive therapy + supportive therapy | 10 | 54/77 |

| C | 72 | – | – | – | Supportive care | 43/72 | ||

| Maes BD 2004, (10) | E | 21 | 39 (11.0) | – | – | Combination: salt restriction, angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibition and MMF 2 g/day | 3 | 19/21 |

| C | 13 | 43 (15.0) | – | – | Placebo | 12/13 | ||

| Manno C 2009, (11) | E | 48 | 34.9 (11.2) | 97.5 (27.7) | 1.07 (0.26) | Prednisone + basic therapy | 8 | 46/48 |

| C | 49 | 31.8 (11.3) | 100.4 (26.1) | 1.08 (0.32) | Basic treatment | 36/49 | ||

| Pozzi C 2004, (12) | E | 43 | – | – | – | Methylprednisolone + supportive therapy | 10 | 41/43 |

| C | 43 | – | – | – | Supportive care | 23/43 | ||

| Tang SC 2010, (13) | E | 20 | 42.1 (2.6) | 52.5 (4.40) | – | MMF + supportive care | 6 | 18/20 |

| C | 20 | 43.3 (2.8) | 50.0 (4.51) | – | Supportive care | 11/20 |

E, experiment; C, control; MMF, mycophenolate mofetil; SCR, serum creatinine; SD, standard deviation.

Risk assessment of bias of included literatures

We used the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Review of Interventions to evaluate the studies included in the meta-analysis. All the articles mentioned random sequence grouping. Only one study (7) did not mention allocation concealment. Other articles described classification concealment. All of the articles mentioned the blind method, and all articles set observation time points, and included detailed descriptions of any drop-out cases. No selective reporting bias or other bias was found, as shown in Table 2.

Table 2

| Study | Random sequence generation | Classification hiding | Blind method | Data integrity | Optional reporting | Other bias |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lv J 2017, (7) | Low (random number) | Unclear | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| Kamei K 2011, (8) | Low (computerized randomization) | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| Rauen T 2020, (9) | Low (computerized randomization) | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| Maes BD 2004, (10) | Low (computerized randomization) | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| Manno C 2009, (11) | Low (unknown) | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| Pozzi C 2004, (12) | Low (computerized randomization) | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| Tang SC 2010, (13) | Low (computerized randomization) | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low |

Analysis of the effects of immunosuppressive drugs on long-term IgA nephropathy

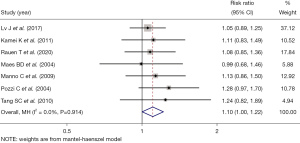

The meta-analysis of the efficacy of immunosuppressive drugs in the long-term treatment of IgA nephropathy showed that the long-term renal function integrity rate in the experimental group treated with immunosuppressive drugs was higher than that in the control group treated with placebos (RR =1.10, 95% CI: 1.00, 1.22, Z=1.978, P=0.048; see Figure 2).

Subgroup analysis

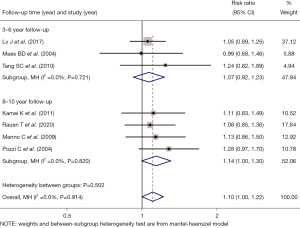

The patients were further divided into follow-up groups of 3–6 and 8–10 years for comparison. The efficacy of immunosuppressive drugs was examined for 3–6 years (RR =1.07, 95% CI: 0.92, 1.23, Z=0.864, P=0.388) and 8–10 years (RR =1.14, 95% CI: 1.00, 1.30, Z=1.909, P=0.056). The results of the two subgroups were similar, indicating that the long-term effects of immunosuppressive drugs still continued with the increase of time (see Figure 3).

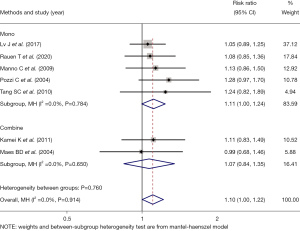

The patients were further divided into two subgroups: monotherapy and combination therapy. The efficacy of immunosuppressive drugs alone (RR =1.11, 95% CI: 1.00, 1.24, Z=1.914, P=0.056) was similar to that of a combination drug (RR =1.07, 95% CI: 0.84, 1.35, Z=0.549, P=0.583), indicating that combination therapy had no advantage over monotherapy (see Figure 4).

Safety analysis of immunosuppressive drugs

Four articles (7,9,10,13) statistically analyzed the adverse reactions of immunosuppressive drugs. The results of the combined analysis showed that the adverse reactions of the immunosuppressive drug group were higher than those of the placebo group (RR =1.59, 95% CI: 1.38, 1.85, Z=6.230, P=0.000; see Figure 5).

Sensitivity analysis

The sensitivity analysis showed that the study results of 7 articles had a similar distribution on both sides and good stability (see Figure 6).

Analysis of publication bias

The funnel plot showed that the left and right distributions of the 7 articles were basically symmetrical, indicating that there was no significant publication bias (see Figure 7).

Discussion

IgA nephropathy is a common glomerular disease that accounts for about 30–40% of all nephropathies (14). As its predisposing mechanism remains unclear, there are still no perfect treatment guidelines. To slow down the development of the disease and protect renal function, it is necessary to take measures according to the different conditions of patients (15). As IgA nephropathy is caused by immune complex deposition, immunosuppression has become a treatment; however, the efficacy of immunosuppressive agents remains controversial (16). Seven articles on the long-term efficacy of immunosuppressive agents were included in this study. The combined statistical results showed that the health rate of combined renal function in the immunosuppressive drug group was higher than that in the placebo group. The 7 articles were divided into short-term follow-up (3–6 years) and long-term follow-up (8–10 years) groups according to the length of the follow-up period. The results showed that there was no significant difference in the long-term efficacy between the two subgroups, which suggests that the long-term efficacy of immunosuppressive agents in the treatment of IgA nephropathy is still good. The 7 articles were also divided into single drug (5 articles) and combined drug (2 articles) groups according to whether or not there was combined drug administration. The combined effect size results showed that there was no significant difference in the long-term effects of the 2 drugs on the renal function health rate of patients; thus, administering a combination of drugs did not improve the efficacy of the treatment. Some studies (4) used corticosteroids combined with azathioprine in the treatment of IgA nephropathy and compared the efficacy with that to 1 drug. The results showed that there was no difference in the efficacy between the 2 treatment methods, but that the combination method had more adverse reactions. Research (17) suggests that the combination of corticosteroids with MMF may increase the risk of severe pneumonia. However, as only two articles examining combination therapy were included in this study, the evidence on this issue is insufficient. More clinical studies need to be conducted to compare the effects of combination therapy and single drug therapy.

Additionally, 4 articles examined the occurrence of adverse reactions. A meta-analysis combined with effect size showed that the use of immunosuppressive agents increased the risk of adverse reactions. It is pointed out in the literature (7) that common adverse reactions in patients treated with immunosuppressive therapy include respiratory tract infection, pneumonic cystic pneumonia, gastrointestinal bleeding, and duodenal ulcer, and these mostly occur in the early stage of the follow-up periods. The literature (13) reported low level of hemoglobin diarrhea, upper gastrointestinal upset during the immunosuppressive therapy, but no drug discontinuation happened after dose adjustment, it also reported two of urinary tract infection, and one of cervical lymphadenitis, which were managed by offering oral antibiotic treatment. Despite the adverse reactions, the benefits of immunosuppressive drugs for IgA nephropathy were still significant.

In this meta-analysis, some studies [e.g., the study by (8)] only stated that the intervention was immunosuppressive therapy, and did not state which drug had been used; thus, an analysis could not be undertaken of the different types of drugs. In the study by Tan et al. (18), MMF appeared to be more suitable for patients with a mild disease, and had a significant effect in reducing proteinuria.

In this study, the random sequence generation and blind method were described in detail. Only one article (7) failed to describe the classification concealment. All the articles provided detailed information about patient drop-out during the follow-up period. Thus, the articles had a small risk of bias. The sensitivity analysis showed that the results were stable. The publication bias analysis showed that there was no significant publication bias. In the study by Tian et al. (19), articles were included to analyze the long-term effects of immunosuppressive therapy; however, the articles included were older (i.e., had all been published before 2010), and the quality of the studies was poor (most failed to men mention the random sequence, allocation concealment and blind method). Thus, the evidence of the present study is better.

This study had a number of limitations. First, the treatment regimens adopted for different age levels, renal function levels, and disease development status differed; however, patients with consistent baseline data should be selected for research as far as possible. Second, there are many immunosuppressive treatment regimens, and while this meta-analysis evaluated their efficacy overall, the efficacy of different regimens needs to be examined separately.

Conclusions

In summary, the use of immunosuppressive drugs can improve the long-term effects of IgA nephropathy treatment, but consideration should be given to the increase of adverse reactions during treatment. As this study had some limitations, this topic needs to be further explored by conducting more RCTs of a higher quality in clinical practice.

Acknowledgments

Funding: None.

Footnote

Reporting Checklist: The authors have completed the PRISMA reporting checklist. Available at https://dx.doi.org/10.21037/apm-21-2883

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at https://dx.doi.org/10.21037/apm-21-2883). The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- Suzuki H, Kiryluk K, Novak J, et al. The pathophysiology of IgA nephropathy. J Am Soc Nephrol 2011;22:1795-803. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Selvaskandan H, Cheung CK, Muto M, et al. New strategies and perspectives on managing IgA nephropathy. Clin Exp Nephrol 2019;23:577-88. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Rauen T, Fitzner C, Eitner F, et al. Effects of Two Immunosuppressive Treatment Protocols for IgA Nephropathy. J Am Soc Nephrol 2018;29:317-25. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Pozzi C, Andrulli S, Pani A, et al. IgA nephropathy with severe chronic renal failure: a randomized controlled trial of corticosteroids and azathioprine. J Nephrol 2013;26:86-93. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Tan J, Dong L, Ye D, et al. The efficacy and safety of immunosuppressive therapies in the treatment of IgA nephropathy: A network meta-analysis. Sci Rep 2020;10:6062. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Natale P, Palmer SC, Ruospo M, et al. Immunosuppressive agents for treating IgA nephropathy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2020;3:CD003965 [PubMed]

- Lv J, Zhang H, Wong MG, et al. Effect of Oral Methylprednisolone on Clinical Outcomes in Patients With IgA Nephropathy: The TESTING Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA 2017;318:432-42. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kamei K, Nakanishi K, Ito S, et al. Long-term results of a randomized controlled trial in childhood IgA nephropathy. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2011;6:1301-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Rauen T, Wied S, Fitzner C, et al. After ten years of follow-up, no difference between supportive care plus immunosuppression and supportive care alone in IgA nephropathy. Kidney Int 2020;98:1044-52. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Maes BD, Oyen R, Claes K, et al. Mycophenolate mofetil in IgA nephropathy: results of a 3-year prospective placebo-controlled randomized study. Kidney Int 2004;65:1842-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Manno C, Torres DD, Rossini M, et al. Randomized controlled clinical trial of corticosteroids plus ACE-inhibitors with long-term follow-up in proteinuric IgA nephropathy. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2009;24:3694-701. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Pozzi C, Andrulli S, Del Vecchio L, et al. Corticosteroid effectiveness in IgA nephropathy: long-term results of a randomized, controlled trial. J Am Soc Nephrol 2004;15:157-63. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Tang SC, Tang AW, Wong SS, et al. Long-term study of mycophenolate mofetil treatment in IgA nephropathy. Kidney Int 2010;77:543-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hassler JR. IgA nephropathy: A brief review. Semin Diagn Pathol 2020;37:143-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Perše M, Večerić-Haler Ž. The Role of IgA in the Pathogenesis of IgA Nephropathy. Int J Mol Sci 2019;20:6199. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Vecchio M, Bonerba B, Palmer SC, et al. Immunosuppressive agents for treating IgA nephropathy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2015;CD003965 [PubMed]

- Wan QJ, Hu HF, He YC, et al. Severe pneumonia in mycophenolate mofetil combined with low-dose corticosteroids-treated patients with immunoglobulin A nephropathy. Kaohsiung J Med Sci 2015;31:42-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Tan CH, Loh PT, Yang WS, et al. Mycophenolate mofetil in the treatment of IgA nephropathy: a systematic review. Singapore Med J 2008;49:780-5. [PubMed]

- Tian L, Shao X, Xie Y, et al. The long-term efficacy and safety of immunosuppressive therapy on the progression of IgA nephropathy: a meta-analysis of controlled clinical trials with more than 5-year follow-up. Expert Opin Pharmacother 2015;16:1137-47. [Crossref] [PubMed]

(English Language Editor: L. Huleatt)