Reflections on a case of Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada syndrome first diagnosed in internal medicine: a case report

Introduction

Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada syndrome (VKH) is a class of systemic autoimmune diseases that mainly targets melanin-related antigens (1,2). It is mainly characterized by bilateral diffuse granulomatous uveitis, meningeal stimulation, vitiligo, and hearing impairment, with a long and repeated course (3-5). Neurological and auditory manifestations usually precede the involvement of other sites in the diversity of clinical manifestations (6). In this paper, we report a case of VKH first diagnosed in neurology. We present the following article in accordance with the CARE reporting checklist (available at https://apm.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/apm-22-248/rc).

Case presentation

The patient was a 73-year-old Chinese female; her chief complaint was a headache for more than 20 days and visual loss for 2 weeks. The patient first felt rear occipital pain two or three times a day, especially at night, and had nausea and vomiting. Gradually her vision decreased with increased body temperature, so she was admitted to the Department of Neurology of Shengli Oilfield Central Hospital. The patient had a history of hypertension for more than 20 years, coronary heart disease for 5 years, carrying the hepatitis B virus for more than 70 years, and binocular cataract surgery. There was no history of ocular trauma and relevant past interventions.

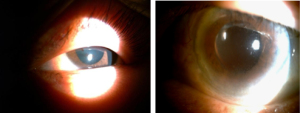

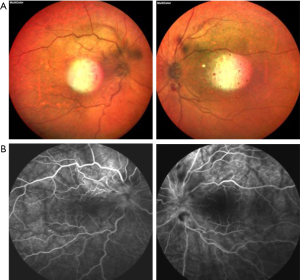

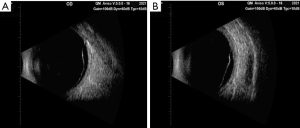

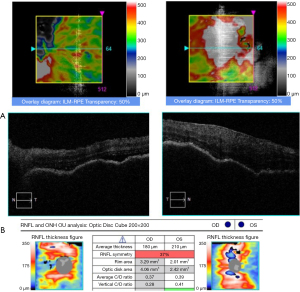

After admission, the physical examination showed that the patient’s temperature was 36.8 ℃, pulse rate was 92 S/C, respiratory rate was 18 S/C, and blood pressure was 145/81 mmHg. Neurology physical examination showed that the patient has decreased vision in both eyes. The ocular examination showed that the vision in the patient’s right eye was FC/20 cm and in her left eye was hand movement (HM), and the intraocular pressure in her right eye was 9 mmHg and in her left eye was 8 mmHg. The conjunctiva was congested in both eyes with the keratic precipitates (+++). Her pupils were dilated and showed iris local posterior adhesion. The vitreous was cloudy, and both ocular optical discs had edema (Figures 1,2). After admission, systemic examination was performed (Table 1). Dexamethasone and acyclovir antiviral treatment were used because the infection was suspected in the skull. The fundus fluorescence examination showed optic disc hyperfluorescence with both eyes exudative retinal detachment (Figure 3). Type-B ultrasonography showed a large number of flocculent opacities in the vitreous (Figure 4). Optical coherence tomography (OCT) showed that significant edema was evident in the macular area and papillary, and there were wavy changes in the retinal pigment epithelium layer (Figure 5). From these data, we diagnosed VKH. The patient refused systemic methylprednisolone shock therapy but gave informed consent to be treated with a 10 mg intravenous injection of dexamethasone and oral administration of entecavir (0.5 mg/qd). The patient is currently in the follow-up observation period. The patient’s nausea and vomiting disappeared after intravenous injection of dexamethasone, but her vision did not improve significantly. During the intervention period, the patient had good compliance, and no adverse events or accidents occurred.

Table 1

| Laboratory tests | Clinical manifestations |

|---|---|

| Clinical examination | Rear occipital pain two or three times a day, nausea and vomiting, visual vision |

| Other medical illnesses | Hypertension, coronary heart disease, carrying hepatitis B virus, and binocular cataract surgery |

| Ocular | Fundus-exudative retinal detachment, Visual acuity diseased, iris local posterior adhesion, keratic precipitates (+++), vitreous was cloudy, both ocular optical discs had edema |

| Ear | Normal |

| Skin | Normal |

| Neurological | No deficits |

| Pain | A headache for more than 20 days and rear occipital pain two or three times a day, especially at night, and had nausea and vomiting |

| Temperature | Increased: 36.8 ℃ |

| Complete blood count + CPR | Normal |

| Urine analysis | Normal |

| Brain magnetic resonance imaging | A small amount of ischemia and abnormal binocular bulb signals in the brain |

| Bilateral carotid artery Doppler | The left internal jugular vein, the left transverse sinus, and the sigmomentous sinus were contralateral slender, and the left transverse sinus locally seemed to have a filling defect |

| Musical calcium triplet | Normal |

| BNP measurement | Normal |

| Hepatitis B triple system examination | HBsAg, HBcAb, Pre-SlAg are positive |

| Cerebrospinal fluid inspection | A negative antiacid bacteria smear and a negative cryptococcal neotype antigen test |

| CSF biochemical examination | Leukocyte count: 125.0×106/L |

| CS-TP: 47.8 mg/dL and Chloride in cerebrospinal fluid: 121.8 mmol/L | |

| Chest imaging (X-ray/CT) | Normal |

| OCT | Significant edema in the macular area and wavy changes in the retinal pigment epithelium layer |

| Fundus fluorescein angiogram | Disc high fluorescence with exudative retinal detachment |

| B scan of orbit | A large number of flocculent opacities in the vitreous |

| Treatment | 10 mg intravenous injection of dexamethasone and oral administration of entecavir (0.5 mg/qd) |

CPR, C reactive protein; BNP, type B sodium urine peptide; HBsAg, hepatitis B surface antigen; HBcAb, hepatitis B surface core antibody; Pre-SlAg, Pre-S1 antigen of hepatitis B virus; CSF, cerebrospinal fluid; CT, computed tomogram; OCT, optical coherence tomography.

All procedures performed in this study were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee(s) and with the Helsinki Declaration (as revised in 2013). Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the editorial office of this journal.

Discussion

Reporting of VKH began in 1873 by Vogt (1906), Koyanagi (1929), and Harada (1926), respectively, describing cases with different symptoms, which Bronstein referred to collectively as VKH or uveitis encephalitis syndrome. It is an immunemediated disorder. The literature states that autoantigens are melanocyte-specific proteins, such as tyrosinases and tyrosine-associated proteins 1 and 2. Predisposing factors include viral infection, human race and specific human leukocyte antigen (HLA) haplotypes A (HLA DRB1*0405 and HLA DQ4) (7). VKH has been reported around the world, with a distinct geographical distribution, mostly in Japanese and Chinese patients (8).

The clinical course of VKH syndrome can be divided into prodromal, acute uveitis, convalescent, and chronic recurrent tages. Neurological and auditory involvement occur in the prodromal stage. Ocular involvement occurs in acute uveitis, convalescent, or chronic recurrent stage, whereas skin involvement occurs in the convalescent stage (9). VKH is divided into complete, incomplete, or probable type. Shivaram et al. (6) reported two patients who had incomplete and complete VKH syndrome and indicated that the headache associated with blurred vision is a red flag. Chen et al. (10) analyzed the retrospective data of three patients with VKH and found that three patients were first diagnosed with different degrees of meningitis, an increased number of leukocytes in their cerebrospinal fluid examination, and mild to moderate inflammatory changes in the meninges were. For these patients, the prognosis was good, and brain parenchymal damage was rare. However, the mechanism of brain parenchyma damage remains unclear and may be associated with enhanced Intracranial osmotic pressure. Furthermore, Lai et al. (11) also described a patient with VKH involving multiple organs who developed ocular symptoms alongside rare joint pain and tablet infiltration of the lungs.

The patient we reported had incomplete VKH syndrome. We need to know that headache and vision loss may be the initial manifestations of VKH disease. When neurological features precede ocular involvement, we should consider the incomplete VKH possibility.

The case report shows that the combination of multiple examinations can effectively reduce the rate of misdiagnosis and is very valuable for clinical confirmation. and remind us that we should be familiar with different clinical symptoms of diseases to avoid misdiagnosis and delay in treatment during the diagnosis and treatment process.

At present, the treatment of VKH is mainly hormone therapy. However, our patient has poor cooperation and she is very resistant to the long-term use of hormone, so the patient is only followed up after the clinical symptoms improvement.

Acknowledgments

Funding: None.

Footnote

Reporting Checklist: The authors have completed the CARE reporting checklist. Available at https://apm.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/apm-22-248/rc

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at https://apm.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/apm-22-248/coif). The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. All procedures performed in this study were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee(s) and with the Helsinki Declaration (as revised in 2013). Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the editorial office of this journal.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- Tsai HJ, Tseng CP. The adaptor protein Disabled-2: new insights into platelet biology and integrin signaling. Thromb J 2016;14:28. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Tao W, Moore R, Smith ER, et al. Endocytosis and Physiology: Insights from Disabled-2 Deficient Mice. Front Cell Dev Biol 2016;4:129. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Finkielstein CV, Capelluto DG. Disabled-2: A modular scaffold protein with multifaceted functions in signaling. Bioessays 2016;38:S45-55. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Huang CL, Cheng JC, Stern A, et al. Disabled-2 is a novel alphaIIb-integrin-binding protein that negatively regulates platelet-fibrinogen interactions and platelet aggregation. J Cell Sci 2006;119:4420-30. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Morris SM, Cooper JA. Disabled-2 colocalizes with the LDLR in clathrin-coated pits and interacts with AP-2. Traffic 2001;2:111-23. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Shivaram S, Nagappa M, Seshagiri DV, et al. Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada Syndrome - A Neurologist's Perspective. Ann Indian Acad Neurol 2021;24:405-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lavezzo MM, Sakata VM, Morita C, et al. Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada disease: review of a rare autoimmune disease targeting antigens of melanocytes. Orphanet J Rare Dis 2016;11:29. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Yang PZ. Inuveitis. Beijing: People's Health Publishing House, 1998:311-6.

- Lueck CJ. Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada syndrome: what neurologists need to know. Pract Neurol 2019;19:278-81. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Chen L, Xu G, Tong Q. A report of 3 cases with Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada syndrome. The Chinese Journal of Modern Neurological Diseases 2008;8:56-8.

- Lai Y, Wang J, Zeng F. Analysis of Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada syndrome with multiple organ involvement. The Chinese Journal of Misdiagnosis 2006;6:4275-6.

(English Language Editor: C. Mullens)