Perception of bedside teaching within the palliative care setting—views from patients, students and staff members

Introduction

There is an increasing demand on end of life education in medical schools. While most students learn about the various aspects of palliative care, death, dying, and the ethical considerations in the classroom, best practice models for teaching these sensitive issues at the bedside are virtually absent. At the same time, simulation centers increasingly shape modern medical education in German speaking countries around Europe (1,2). Indeed, as skill requirements increase and catalogs like the Canadian CANMEDS acting model (3) or the German NKLM (the National competency-based learning-goal catalog) (4) are being used as guiding principles in different fields of medical education. Simulation centers possess various advantages: students feel comfortable in these simulated situations appreciating the possibility to make mistakes in a controlled surrounding, getting professional feedback and using the opportunity of repetition. For faculty, medical education within simulated situations becomes easy to plan and control (5).

At the same time, bedside teaching is losing its relevance in medical education. However, for apprentices the experience of direct contact to real patients cannot be substituted by simulating scenarios (6,7). Bedside teaching has shown to improve clinical skills and abilities even allowing to enhance the self-assessment by students (8). Direct contact to cancer patients has shown to cause a stronger beneficial effect on communication skills than contact to patients with other diagnoses (9). Sir William Osler [1849–1919] a pioneer of medical education, said: “Medicine is learned by the bedside and not in the classroom!” (10). When planning bedside teaching in the palliative care settings, further aspects need to be considered: (I) patients and students facing with end-of-life aspects will experience emotional challenges—however, these will be different for students and patients; (II) students’ education must by no means cause any discomfort for the patients; and (III) there are the interests of the nursing staff who often appear paternal towards patients comfort and therefore object bedside teaching (11). However, bedside teaching assures the close interaction between apprentice and patient with their own individual distress and personal experience facing incurable illness in real life, not just by means of physical distress but also experiencing fundamental effects on psychosocial and spiritual well-being. In 2011, Harris suggested implementation of certain strategies and rules for bedside teaching in palliative care settings to minimize the potential disadvantages for students and patients (12). However, the overall assumption that terminally ill patients should be excluded from bedside teaching has not been confirmed in the literature (13).

The aim of this study was twofold: (I) to analyze the perception of bedside teaching on a palliative care ward from the perspectives of students, staff members and patients; and (II) to define the prerequisites for an efficient and patient-centered bedside teaching on palliative care wards.

Methods

Clinical context

The 14-bed facility is cared for by nine nurses, two doctors, a social worker, a documentarist, a psycho-oncologist and members of the physiotherapeutic care team for the inpatients. Various volunteers complete the team.

Study design

Elective courses “Intensive Practical Training Palliative care” on the palliative care ward were offered in two consecutive terms—summer 2016 and winter 2016/2017—to students in their clinical educational phase.

These courses were structured the following: Each student was assigned one patient each on two consecutive days. The respective patient’s records were made available to the students before they were asked to interview and examine their patients. The students were then asked to draft a treatment plan that met the standards of palliative care and included appropriate laboratory diagnostics, imaging procedures, drug therapy, drugs on demand as well as additional invasive and noninvasive therapies where necessary. During the course, all anamnestic and laboratory findings and prescriptions were discussed in plenary seminars in the absence of any patient. Conspicuous findings mentioned by students were reviewed and then re-examined at the bedside. The course was completed by a bed sided mini-clinical examination that was graded by one faculty member.

Participants

Patients

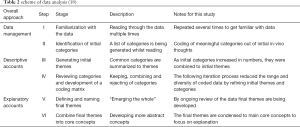

All inpatients were screened for eligibility of participation. Exclusion criteria were low performance status, high symptom load, short life expectancy and short time of stay on ward. Included patients were informed about the forthcoming student teaching and were invited to participate in the bedside teaching. Patients’ agreements were obtained at least 24 hours prior to the upcoming teaching unit. On some days, no patient consented or did not qualify for participation due to symptom load or low ECOG performance status. Therefore, individual patients volunteered for different students on two consecutive days. One patient participated but died before the final bed sided mini-clinical examination. The evaluation of patients’ perceptions were carried out in the form of semi-structured interviews (Table 1). Interviewers were instructed how to lead through the interview. Each patient was only interviewed once, even though some patients were available for two students on different days. Interviews were held without any interruption and lasted 20 to 45 minutes in either single or double bed rooms on the ward.

Full table

Students

Students who enrolled in the elective course “Intensive Practical Training Palliative care” were invited to participate in this study. Participants were assessed by self-constructed questionnaires both, before and after completion of the course. Students were asked to answer open questions about special features of the palliative care situation. There was no time limit for working through the questionnaire, the process was not interrupted.

Staff

Members of the palliative care team were also invited to participate in this study and answer a questionnaire concerning their perception of different aspects of bedside teaching on the palliative care ward. Those who participated were either providing primary or secondary patient care or were voluntary workers.

All participants were directly approached by the same person and invited to participate in the study. Participation was strictly voluntary. Inclusion required the signing of an informed consent form.

Data collection and analysis

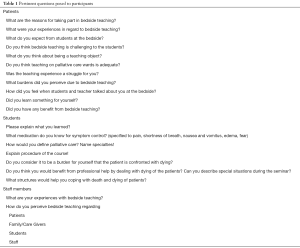

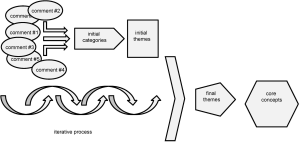

Patients and students were asked to report their experiences during bedside teaching, staff members were not part of the respective courses and expressed their perceptions of bedside teaching on the palliative care ward retrospectively. Data were then analyzed qualitatively following the framework approach (14,15), using the subsequent steps: (I) familiarization with the data, (II) identification of initial categories, (III) generation of initial themes, (IV) development of a coding matrix and assignment of suitable data into the matrix; (V) re-reading through the data and re-organization of initial themes into more abstract categories to formulate final themes (VI) combine final themes into core concepts (16,17) (Table 2). The aim was to recruit sufficient participants in each group of patients, students and staff to reach a saturation of arguments. Saturation was assessed by an ongoing analysis of the interviews (Figure 1).

Results

A total of 20 patients, 21 medical students, and 19 staff members participated in the study and provided for a saturation of arguments. Qualitative analysis of the data following the framework approach revealed five core concepts related to bedside teaching on the palliative care ward. These core concepts are based on pertinent comments (Table 3) and can be summarized as follows:

Full table

Core concept 1: best possible end-of-life education for students

Most patients participating in the course saw the need of best possible education in all subjects. Patients stated that bedside teaching was a good option to teach students. Being a part of the process made patients proud as expressed by a patient as follows: “I hope I can help them……understand my very special situation.”

Students enjoyed being around real patients. Their perceived learning input increased due to reality (manuscript in preparation). Some students mentioned bedside teaching to be the most important part of teaching medicine, irrespective of the clinical subject. Treatments in palliative care setting usually aim at achieving the best possible quality of life rather than pointing at the cause. This major difference was recognized by most students.

For team members, bedside teaching is an important way of teaching and learning. None of the team members questioned bedside teaching as a fundamental part in medical education, not even in palliative care.

Core concept 2: benefit of bedside teaching for participants

Patients mostly wanted to help. Two themes emerged repeatedly during the interviews—being helpful for students so that they will understand the subject and helping in improving the education of future doctors so that future patients will benefit from better care. “Making the best out of it.” Some patients felt bored and left alone on the ward. However, these feelings did not correlate with any contact to family members, frequencies of visits or nearness of home. Even though one patient stated that he didn’t have any contact at all, this patient did not mention diversion to be his first motivation to take part in the seminar. He declared: “I am here, and I don’t have anything else to do!” Further on the same patient mentioned that the visit of the students was a “nice diversion, but no enrichment!” Another patient mentioned “Boredom!” as his major motivation factor. Some patients mentioned better care as a motivating factor to participate in bedside teaching.

Students enjoyed the benefit of reality as they mentioned that real life experiences to be more effective than theory-based seminars.

Team members of nursing staff expected the students to help during daily routines, and were irritated by the lack of benefit for themselves. In contrast, physicians appreciated the students questioning daily routines and standard procedures as they were forced to re-evaluate and were at times prompted to optimize standard operations.

Core concept 3: gain in knowledge, skills and competences

The gain in knowledge, skills and competences applied to students only and will be evaluated quantitatively and described elsewhere. In short, special fields of knowledge were medical treatment, phases of dying or definitions of palliative care and were compared before and after the course on bedside teaching. Practical skills like communication with terminally ill and dying patients were part of the hidden curriculum.

Core concept 4: disturbances to patients and team

Symptom load is one of the aspects in palliative care that can lead to termination of bedside teaching. Palliative care patients as inpatients are usually impaired by distressing symptoms and some patients denied participation in bedside teaching because of breathlessness, fatigue or need of tranquility. However, none of our patients who was eligible for bedside teaching and agreed to participate terminated the student contact due to symptom load.

Patients had clear expectation about what students were allowed to do. To the question what they would expect from students several patients answered that they expected students to know their abilities and respect their limitations. Some patients feared that the contact with students would worsen their own grief.

All members of the team have a tight time schedule. Due to understaffing patient care, communication needs, need of medical decisions and educational obligations might compete with each other. Staff members perceived this as a threat. “Since we have a lack of physicians, teaching cannot be taken over by our ward physician if teaching has to take place, please only with an additional external teacher.” (nurse).

Core concept 5: reflections on death and dying

Patients became aware of their situation being faced with students. This resulted in pronounced sadness, sometimes even caused by sad looks on the side of the students.

Students participating in our seminar did not mention fear or grief to be a major issue after experiencing palliative care education at the bedside.

Discussion

Because a single patient can tell better than a thousand slides and because experience is sometimes worth more than what we read or hear—no theoretically based seminar can ever replace real life medicine (19). All of the team members recognized palliative care as a very important field in medical care and none of them questioned bedside teaching as a fundamental part in medical education, not even in palliative care. However, medical education in palliative care differs from other subjects, particularly by addressing death, dying and taking care of people that won’t be cured again. The goals and treatment approaches might therefore be different. Understanding the difference between curative and palliative medicine is therefore a fundamental goal in palliative care education.

Patients in palliative care situations were previously cited to consider bedside teaching as valuable (20). Indeed, the responses of our patients taking part in the present study support this view. Being helpful to future patients and physicians as well as killing boredom and seeking distraction were intrinsic motivation factors. However, a careful selection of participating patients is required in order to protect patients with high symptom load, numbness, fatigue or mental restriction. The consciousness of death and dying and worsening of symptom load might disturb patients. It is therefore mandatory and within the responsibility of the teaching staff that the patients are informed about all steps of the course and that the bedside teaching can at any time be terminated by the patients.

Students’ experiences with dying patients are considered to induce a long-term change of attitudes (21). However, most faculties address these experiences within a hidden curriculum (21). Our cohort of students confirmed the benefit of direct contact to patients in palliative care situations and thus support previous recommendations for thoughtful, integrative and interdisciplinary curriculum changes in end-of-life education as psychological and emotional experiences cannot be taught in the classroom (22). Subsequent to the bedside teaching on a palliative care ward, students should be given the opportunity to reflect on what they experienced (23). And even though our students did neither mention fear or grief to be a major issue after experiencing palliative care education at the bedside nor did they express a need for psychological guidance, certain constellations might require professional help which should therefore be kept at hand.

Little is known about the perception of bedside teaching by staff members. Especially the nursing team appears to be paternal towards patients’ needs for quietness and tranquility (12,13). And while the staff’s reservations towards bedside teaching need to be acknowledged, one step towards alleviating these concerns may include a clear communication. Nursing staff members need to be informed about the goals of the bedside teaching, the teaching methods and the teaching staff involved (20). Moreover, they need to be aware of all steps of the teaching course, the time course, which tasks can be delegated to students and they need to know the termination rules. As of yet there is no report on the teaching staffs’ perception of bedside teaching in palliative care. Being triggered to re-evaluate common and standard procedures on the ward is therefore a valuable experience but may be limited to those who are open minded enough to get involved with the young and inexperienced.

There are limitations to our study and they include the numbers of participants. Even though a saturation of arguments was achieved, the present study focused on the statements of very heterogeneous groups. It was intended as an orientating survey to investigate perceptions of bedside teaching from different yet interacting points of view. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study with this particular research question and it proves that the individual perceptions of bedside teaching are heterogenic. Future studies need to address long term benefits as well as possible negative consequences for patients, students and staff members.

Conclusions

The first aim of this study was to analyze the perception of bedside teaching on a palliative care ward from various perspectives. Both, patients and students mostly enjoyed each other’s contact, even though for different reasons. While some of the patients suffered from the renewed confrontation with their own unfavorable fate, none of the students reported any distress from the contact with dying patients. The nursing team felt ambiguously: on the one hand they acknowledged bedside teaching as an important means to teach palliative care, but on the other they expected the students to be of help yet experienced them as an additional burden. The teaching staff perceived the students as an enrichment that triggered the re-evaluation of standard procedures on the ward.

The second aim was to define the prerequisites for an efficient and patient-centered bedside teaching on palliative care wards. The results from our qualitative analysis suggest that bedside teaching requires:

- A clear targeted communication to students and staff alike about the goals of the teaching and the responsibilities of those involved;

- Strict exclusion criteria for the participating patients (high symptom load);

- Empowerment of patients to determine the course, rate and termination of bedside teaching;

- Rules for the patient—student contact: no more than two students per patient, no more than 15 minutes contact at a time;

- Sufficient time slots to address the patients’ and students’ needs for psychological guidance, for example 15 minutes at the end of each working day;

- No less than 5 days duration for the course.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank the office of study affairs of University of Rostock for supporting the studies to the Master of Medical Education for Dr. Ursula Kriesen. We would also like to thank all participants for the involvement in this study and giving their written consent for publication of this study.

Footnote

Conflicts of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: Ethical approval was obtained from the local Ethics Committee of the Rostock University Medical Center (Number A2015-0167). All participants were directly approached by the same person and invited to participate in the study. Participation was strictly voluntary. Inclusion required the signing of an informed consent form.

References

- Segarra LM, Schwedler A, Weih M, et al. Der Einsatz von medizinischen Trainingszentren für die Ausbildung zum Arzt in Deutschland, Österreich und der deutschsprachigen Schweiz. (Clinical skills Labs in Medical Education in Germany, Austria and German Speaking Switzerland.) GMS Z Med Ausbild 2008;25:Doc80.

- Schnabel KP, Stosch C. Practical Skills en route to Professionalism. GMS J Med Educ 2016;33:Doc66. [PubMed]

- Frank JR. CanMEDS 2005 Physician Competency Framework. Ottawa: The Royal College; 2005. p.23-24 Available online: http://www.ub.edu/medicina_unitateducaciomedica/documentos/CanMeds.pdf. Accessed 11 Aug 2016

- Hahn EG, Fischer MR. Nationaler Kompetenzbasierter Lernzielkatalog Medizin (NKLM) für Deutschland: Zusammenarbeit der Gesellschaft für Medizinische Ausbildung (GMA) und des Medizinischen Fakultätentages (MFT). GMS Z Med Ausbild 2009;26:Doc35.

- Qureshi Z. Back to the bedside: the role of bedside teaching in the modern era. Perspect Med Educ 2014;3:69-72. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Nair BR, Coughlan JL, Hensley MJ. Student and patient perspectives on bedside teaching. Med Educ 1997;31:341-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Peters M, Ten Cate O. Bedside teaching in medical education: a literature review. Perspect Med Educ 2014;3:76-88. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Fünger SM, Lesevic H, Rosner S, et al. Improved self- and external assessment of the clinical abilities of medical students through structured improvement measures in an internal medicine bedside course. GMS J Med Educ 2016;33:Doc59. [PubMed]

- Klein S, Tracy D, Kitchener HC, et al. The effects of the participation of patients with cancer in teaching communication skills to medical undergraduates: a randomised study with follow-up after 2 years. Eur J Cancer 2000;36:273-81. [PubMed]

- Stone MJ. The wisdom of Sir William Osler. Am J Cardiol 1995;75:269-76. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wee B. Bedside teaching. In: Wee B, Hughes N, editors. Education in Palliative Care. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2007:15-25.

- Harris DG. Overcoming the challenges of bedside teaching in palliative care setting. BMJ Support Palliat Care 2011;1:193-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Harris DG, Coles B, Willoughby HM. Should we involve terminally ill patients in teaching medical students? A systematic review of patient’s views. BMJ Support Palliat Care 2015;5:522-30. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gale NK, Heath G, Cameron E, et al. Using the framework method for the analysis of qualitative data in multi-disciplinary health research. BMC Med Res Methodol 2013;13:117. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ritchie J, Lewis J. Qualitative research practice: a guide for social science students and researchers. London: Sage; 2003. Available online: https://mthoyibi.files.wordpress.com/2011/10/qualitative-research-practice_a-guide-for-social-science-students-and-researchers_jane-ritchie-and-jane-lewis-eds_20031.pdf

- Fortney CA, Steward DK. A qualitative study of nurse observations of symptoms in infants at end-of-life in neonatal intensive care unit. Intensive Crit Care Nurs 2017;40:57-63. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Taylor P, Dowding D, Johnson M. Clinical decision making in the recognition of dying: a qualitative interview study. BMC Palliat Care 2017;16:11. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Smith J, Firth J. Qualitative data analysis: the framework approach. Nurse Res 2011;18:52-62. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Qureshi Z. Back to the bedside: the role of bedside teaching in the modern era Perspect Med Educ 2014;3:69-72. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Franks A, Rudd N. Medical student teaching in a hospice - what do the patients think about it? Palliat Med 1997;11:395-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Smith-Han K, Martyn H, Barrett A, et al. That’s not what you expect to do as a doctor, you know, you don’t expect your patients to die.” Death as a learning experience for undergraduate medical students. BMC Med Educ 2016;16:108. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wear D. ‘‘Face-to-face with It’’: Medical Students’ narratives about their end-of-life education. Acad Med 2002;77:271-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Williams CM, Wilson CC, Olsen CH. Dying, death, and medical education: student voices. J Palliat Med 2005;8:372-81. [Crossref] [PubMed]