Management of radiation-induced nausea and vomiting with palonosetron in patients with pre-existing emesis: a pilot study

Introduction

Nausea and vomiting is commonly experienced by patients in advanced stages of cancer, and can be multifactorial in nature. The symptoms may be caused or influenced by the disease itself (1). Tumours may cause nausea or vomiting through elevated intracranial pressure, bowel obstruction, or ascites. The symptoms may be consequent to previous therapies, such as chemotherapy, or current medications. For example, up to 40% and 25% of patients experience opioid-induced nausea and vomiting respectively (2). Additionally, other symptoms such as anxiety and pain may trigger or exacerbate nausea (1). Untreated, severe or persistent vomiting can cause physical complications such as nutritional deficiency, weight loss, electrolyte imbalances and dehydration (3,4).

Over 50% of patients undergoing radiotherapy may experience radiation-induced nausea and vomiting (RINV) (5). In patients with pre-existing emesis, radiation may increase severity of the symptom, further compromising quality of life (QOL). However, patients with pre-existing emesis are poorly represented in the current body of literature on treatment of RINV, as they are often excluded in anti-emetic trials. Our group previously conducted a trial using ondansetron, a first-generation serotonin receptor antagonist, on a sample including patients with pre-existing emesis (6). In this pilot study using palonosetron, a second-generation serotonin receptor antagonist, we investigated rates of control of RINV in patients with pre-existing emesis.

Methods

Patients and treatment

Patients with pre-existing emesis were eligible if they were undergoing palliative radiotherapy to sites categorized as moderate or low risk for RINV by the cooperative guidelines from the Multinational Association of Supportive Care in Cancer and the European Society for Medical Oncology (7). To minimize other sources of emesis, patients who had received cranial radiation or chemotherapy within 7 days preceding the start of radiotherapy, or were scheduled to receive such treatments during or within 10 days of study treatment, were ineligible. Patients were not eligible if they were scheduled to receive corticosteroid treatment within 48 hours preceding, during or within 10 days following radiotherapy. Patients with a Karnofsky Performance Status (KPS) less than 40 were excluded. Informed consent was provided by all patients, and the study was approved by the hospital research ethics board (No. 434-2013) and Health Canada.

Patients received radiation with one of the three following dose/fractionation schedules: 8 Gray (Gy) in 1 fraction, 20 Gy in 5 fractions or 30 Gy in 10 fractions. Patients were pre-medicated with 0.5 mg of palonosetron orally, at least 1 hour prior to the first fraction of radiation treatment, and every other day until the completion of radiation treatment. Patients who received one fraction of radiation were medicated once, at least 1 hour prior to treatment. Patients were to receive palonosetron on weekends and holidays within the scheduled treatment to ensure continuous coverage.

Data collection

Age, sex, primary cancer site, performance status, and prescribed radiation treatment were collected at baseline.

Study procedure included a daily diary that was completed by patients at baseline, every day during radiation treatment (including weekends and holidays) (Appendix 1), and for 10 days post-treatment. In addition to assessing severity of nausea and vomiting, the daily diary also evaluated diarrhea, the interference of any existing RINV on the patient’s daily life, as well as the patient’s use of anti-emetics. Nausea, vomiting and diarrhea were rated by the patient on level of severity (none, mild, moderate or severe). Patients who had nausea or vomiting were asked to record the number of episodes they experienced and rank its interference with aspects of daily life on a 5-point scale in daily diaries. Research assistants maintained copies of daily diaries through regular telephone follow-ups. Patient diaries were collected at the end of the study period.

Side effects of constipation and headache, as well as other adverse events, were regularly monitored, graded according to the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (Version 4.0), and recorded during follow-up calls with research assistants. At baseline and throughout the study period, patients completed the Functional Life Index-Emesis (FLIE) and the European Organization for the Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire (EORTC QLQ) Core 15-Palliative (C15-PAL).

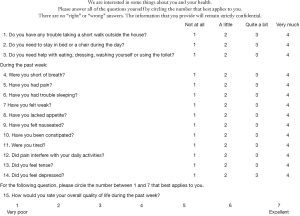

The FLIE evaluates the amounts of nausea (Q1) and vomiting (Q10) and their impact on various aspects of function, including: to maintain usual recreation (Q2, Q11), make a meal/minor repairs (Q3, Q12), enjoy a meal (Q4, Q13) or liquid refreshment (Q5, Q14), see or spend time with loved ones (Q6, Q15), function daily (Q7, Q16). In addition, patients are asked to rate the degree to which nausea and/or vomiting imposes a hardship on themselves (Q8, Q17) and those closest to them (Q9, Q18) (8). All items are assessed with a recall period of 3 days, on a 7-point scale (Appendix 2). Patients completed the FLIE at baseline, days 5 and 10 during treatment (for multiple fractions of radiotherapy), and days 3 and 7 following treatment.

The C15-PAL is a module specific to the palliative patient population, and assesses overall QOL as well as the following 14 items: ability to take a short walk (Q1), need to stay in bed/chair (Q2), need for help (Q3), shortness of breath (Q4), pain (Q5), dyspnea (Q6), weakness (Q7), lack of appetite (Q8), nausea (Q9), constipation (Q10), tiredness (Q11), interference with daily activities (Q12), tenseness (Q13) and depression (Q14) (Appendix 3) (9). All questions use a 4-point scale, with an exception of the overall QOL question, which is answered on a 7-point scale. Higher scores indicate greater functionality, better QOL, and worse symptomology on the respective scales. Patients completed the C15-PAL at baseline, days 5 and 10 during treatment (if applicable), and days 5 and 10 following treatment.

Study definitions

Patients were followed during acute (day 1 of treatment to day 1 post-treatment) and delayed (days 2–10 post-treatment) phases of treatment.

Nausea was defined as a feeling occurring in the areas of the back of the throat to the stomach, often described as queasiness. Nausea may or may not have led to vomiting. Vomiting was defined as the oral forceful expulsion of stomach contents. Other terms used were “throwing up” or “puking”. An episode of vomiting had a distinct starting and ending point, with at least one occurrence of vomiting in between. Individual episodes were separated by the lack of vomiting for at least 5 minutes. Side effects of constipation and headache were patient-reported and defined as per the individual.

Efficacy parameters

Complete prophylaxis (CP) was defined as no increase in use of anti-emetic medication, and no increase in episodes of nausea or vomiting from baseline. Partial control (PC) was defined as an increase of 1–2 episodes of nausea or vomiting, or an increase in use of anti-emetic medication from baseline. Three or more episodes of nausea or vomiting was defined as an uncontrolled response. Prophylaxis and rescue (PR) was defined as a decrease in episodes of nausea or vomiting or a decrease in use of anti-emetic medication from baseline. Responders were participants who experienced either PR or CP with the study treatment.

Statistical analysis

Demographic and medical information were described in all patients as mean and range for age, and as proportions for categorical variables. Proportions of patients achieving PR, CP, PC and uncontrolled response were calculated according to study definitions and presented separately for acute and delayed phases. The proportion of patients with side effects (i.e., constipation, headache) was calculated at baseline, acute phase, and delayed phase. The level of severity and relation to treatment were also described for constipation and headache side effects.

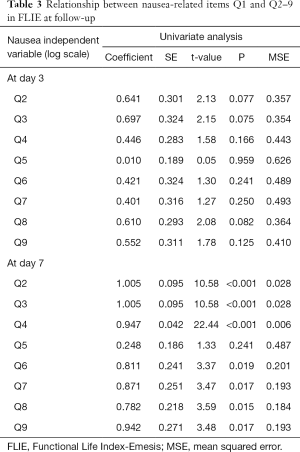

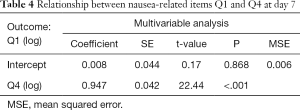

To search for relationships between nausea-related items Q1 and Q2–Q9, univariate and multivariable linear regression analyses were performed at day 3 or at day 7 post-treatment, respectively. Mean squared error (MSE) was estimated for the average of the squares of the error (lower MSE value, better the model fit). Natural log-transformation was applied for all FLIE items, except for Q5 to normalize the distribution.

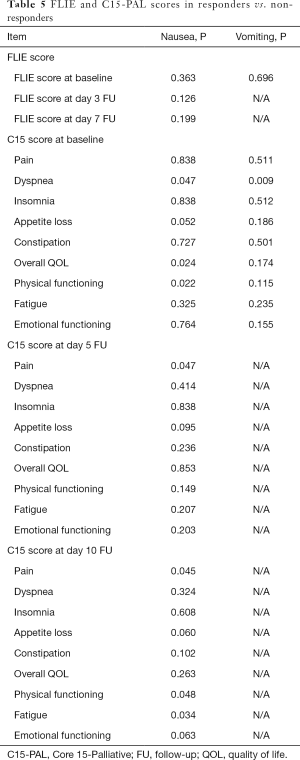

Wilcoxon rank-sum test was used to detect significant differences in FLIE scores at baseline, at day 3 or day 7 follow-up; and in C15-PAL scores at baseline, at day 5 or day 10 follow-up in responders vs. non-responders.

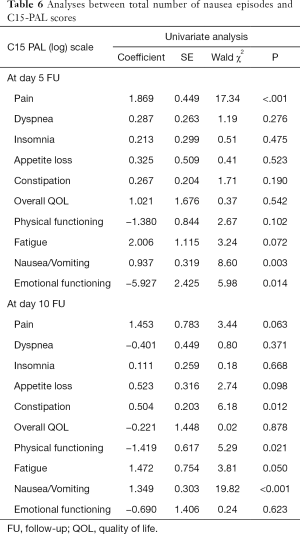

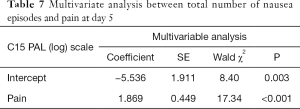

Number of nausea or vomiting episodes was totaled for days 1–5 and days 6–10 post-treatment. The relationships between total episodes and C15-PAL items were conducted using generalized linear model for count data. The GENMOD procedure in Statistical Analysis Software (SAS) was performed, and Poisson distribution with log link function was used. To normalize the distribution, natural log-transformation was applied for all C15-PAL items. All analyses were conducted using SAS (version 9.4 for Windows). P<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Role of the funding source

The funding source had no role in the study design, data collection, analysis or interpretation. All authors had access to all data. The corresponding author had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication.

Results

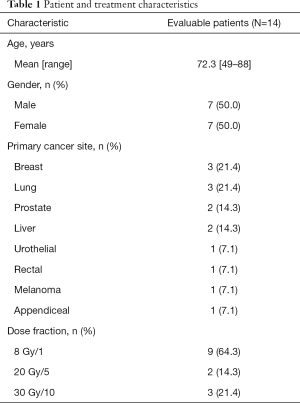

Fourteen patients were enrolled from April 2015 to July 2017. All 14 patients were assessed in the acute phase; and due to one withdrawal, 13 patients were included in the delayed phase. The average age was 72.3 years, and there was equal representation of males and females (Table 1). Of the total 14 patients, 9 (64.3%) received a single fraction of radiation and 5 (35.7%) received multiple fractions of radiation (Table 1).

Full table

Efficacy endpoints

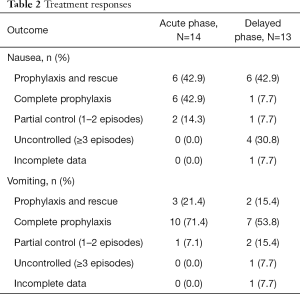

Treatment responses are summarized in Table 2. In the acute phase, 6 (42.9%) patients reported PR of nausea. Another 6 (42.9%) patients reported CP and 2 (14.3%) patients reported PC of nausea. Similarly, 3 (21.4%) and 10 (71.4%) experienced PR and CP of vomiting respectively. One (7.1%) patient reported PC of vomiting.

Full table

In the delayed phase, 6 (42.9%) patients reported PR and 1 (7.7%) patient reported CP of nausea. Another patient (7.7%) reported PC of nausea. Four (30.8%) patients experienced an uncontrolled response, and 1 patient had incomplete data. Similarly, 2 (15.4%) patients reported PR, and 7 (53.8%) patients reported CP of vomiting. Two (15.4%) patients experienced PC, 1 (7.7%) patient reported an uncontrolled response, and 1 patient had incomplete data.

At baseline, 2 patients reported use of anti-emetics. Five patients reported use of anti-emetics during follow-up.

Adverse events

At baseline, 2 (14.3%) and 6 (42.9%) patients experienced headache and constipation respectively. At follow-up, 1 (7.1%) patient reported a mild headache, 5 (35.7%) patients reported mild constipation, and 5 (35.7%) patients reported moderate constipation.

QOL

In Table 3, there were significant adverse relationships between Q1 (amount of nausea) of the FLIE and the remaining items related to nausea at day 7 post-treatment, except Q5 (ability to enjoy liquid refreshments). In the multivariable analysis of nausea, only Q4 (enjoyment of food) remained significantly associated with Q1 at day 7 (Table 4). A similar analysis was unable to be conducted using amount of vomiting due to low levels in the patient sample.

Full table

Full table

Responders in delayed nausea had significantly lower C15-PAL scores in dyspnea (P=0.047), physical functioning (P=0.022) and higher overall QOL (P=0.025) at baseline compared to non-responders (Table 5). Responders in delayed nausea had significantly lower scores in pain compared to non-responders at day 5 (P=0.048), as well as significantly lower scores in pain (P=0.046), physical functioning (P=0.048) and fatigue (P=0.035) at day 10 compared to non-responders. Responders in delayed vomiting had significantly lower C15-PAL scores in dyspnea (P=0.010) at baseline only, compared to non-responders.

Full table

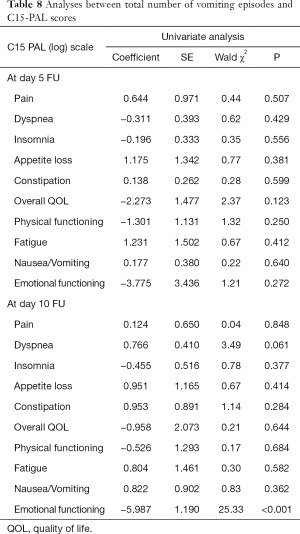

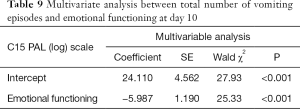

In a univariate analysis of C15-PAL scores, there were significant associations between the number of episodes of nausea and pain (P<0.0001) or emotional functioning (P=0.015) at day 5, as well as constipation (P=0.013) and physical functioning (P=0.021) at day 10 (Table 6). Only pain remained significantly associated to number of nausea episodes in the multivariate analysis at day 5 (P<0.0001) (Table 7). In both univariate and multivariate analyses of number of vomiting episodes on C15-PAL scores, we only found a significant association between the number of episodes of vomiting and emotional function (P<0.0001) at day 10 (Tables 8,9).

Full table

Full table

Full table

Full table

Discussion

When compared with our previous trial (6), our current study demonstrated that 85.8% and 92.8% of patients experienced stabilization or improvement of nausea and vomiting respectively in the acute phase. These rates decreased in the delayed phase to 50.6% and 69.2% in control of nausea and vomiting respectively. The decrease of control from acute to delayed phases is well documented in other serotonin receptor antagonists (10).

In a trial previously conducted by our group using rapidly dissolving film ondansetron, Wong et al. included four patients with pre-existing emesis under the group “secondary prophylaxis” (6). All four patients with pre-existing nausea and both patients with pre-existing vomiting reported complete control with ondansetron during the trial. The authors noted that this formulation of ondansetron may be preferred by patients suffering from nausea and/or vomiting preceding treatment.

In the present study, a multivariate analysis of patient responses to the FLIE demonstrated a significant adverse association between amount of nausea and enjoyment of food. Similarly, the multivariate analysis of patient responses to the C15-PAL demonstrated significant adverse associations between amount of nausea and pain, as well as between amount of vomiting and emotional function. In an analysis of FLIE scores from patients receiving palliative gastrointestinal radiation therapy, Poon et al. observed significant adverse relationships between increased duration of nausea and willingness to see and spend time with loved ones (Q6) (11). There was also a significant adverse relationship between the severity of nausea and ability to maintain usual recreation/leisure activities (Q2). Using the EORTC Core 30 (C30) questionnaire, duration of nausea was significantly related to fatigue, pain, dyspnea and constipation. Severity of nausea was related to three types of functioning (physical, role, social), as well as fatigue, appetite loss, diarrhea, and financial problems.

Radiation to the lower body is thought to induce nausea and vomiting through release of serotonin by enterochromaffin cells in response to damage in the mucosal layer of the gastrointestinal tract (12). There is strong evidence for the use of serotonin (5-HT3) receptor antagonists in chemotherapy- and radiation-induced nausea and vomiting. However, the strength of evidence for these agents in treatment of chronic nausea in palliative care is lacking; therefore, serotonin receptor antagonists are not often used as first-line treatments in this setting. Despite already being treated with other anti-emetics, patients with pre-existing emesis may still require and benefit from added, and more targeted, protection against RINV with serotonin receptor antagonists.

The present study showed promising rates of control with palonosetron; however, due to its small sample size, more investigation regarding PR of RINV in this population is needed.

Conclusions

The majority of patients with pre-existing emesis demonstrated stabilization or improvement of the symptoms during radiotherapy with treatment with palonosetron. It was safe and well-tolerated by study patients. More investigation and guidance on treatment of RINV in patients with pre-existing emesis is needed.

Appendix 1: Daily diary

Appendix 2: FLIE

Appendix 3: C15-PSL

Acknowledgements

We thank Canadian Eisai for the supply of the medication.

Footnote

Conflicts of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: Informed consent was provided by all patients, and the study was approved by the hospital research ethics board (No. 434-2013) and Health Canada.

References

- Harris DG. Nausea and vomiting in advanced cancer. Br Med Bull 2010;96:175-85. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Mallick-Searle T, Fillman M. The pathophysiology, incidence, impact, and treatment of opioid-induced nausea and vomiting. J Am Assoc Nurse Pract 2017;29:704-10. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Collis E, Mather H. Nausea and vomiting in palliative care. BMJ 2015;351:h6249. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Sanchez-Lara K, Ugalde-Morales E, Motola-Kuba D, et al. Gastrointestinal symptoms and weight loss in cancer patients receiving chemotherapy Br J Nutr 2013;109:894-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Feyer P, Jahn F, Jordan K. Prophylactic management of radiation-induced nausea and vomiting. BioMed Res Int 2015;2015. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wong E, Pulenzas N, Bedard G, et al. Ondansetron rapidly dissolving film for the prophylactic treatment of radiation-induced nausea and vomiting - a pilot study. Curr Oncol 2015;22:199-210. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Feyer PC, Maranzano E, Molassiotis A, et al. Radiotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting (RINV): MASCC/ESMO guideline for antiemetics in radiotherapy: update 2009. Support Care Cancer 2011;19 Suppl 1:S5-14. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lindley CM, Hirsch JD, O'Neill CV, et al. Quality of life consequences of chemotherapy-induced emesis. Qual Life Res 1992;1:331-40. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Groenvold M, Petersen MA, Aaronson NK, et al. The development of the EORTC QLQ-C15-PAL: A shortened questionnaire for cancer patients in palliative care. Eur J Cancer 2006;42:55-64. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Li WS, van der Velden JM, Ganesh V, et al. Prophylaxis of radiation-induced nausea and vomiting: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Ann Palliat Med 2017;6:104-17. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Poon M, Hwang J., Dennis K., et al. A novel prospective descriptive analysis of nausea and vomiting among patients receiving gastrointestinal radiation therapy. Support Care Cancer 2016;24:1545-61. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Mawe GM, Hoffman JM. Serotonin signaling in the gastrointestinal tract: functions, dysfunctions, and therapeutic targets. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2013;10:473-86. [Crossref] [PubMed]