Palliative care in Botswana: current state and challenges to further development

Introduction

In 2011, the World Health Organization (WHO) estimated that 29 million people died from causes necessitating palliative care (1). Communities worldwide are facing increasing numbers of chronic and non-communicable diseases. With improved access to treatment and management, HIV has become a chronic disease and other chronic conditions such as cancer and cardiovascular disease are rising in incidence alongside it (2). The need for palliative care has not only continued to grow, but has also remained unmet. Moreover, this need has fallen disproportionately on low- and middle-income countries, where 78% of these 29 million individuals are living (1). These countries are home to 99% of HIV/AIDS and cancer patients who die with untreated pain (2).

Africa faces a unique palliative care burden due to high rates of both communicable and non-communicable diseases (3). Of the 19 million people requiring palliative care at the end of life, 9% alone are in Africa (1). Approximately 1 in 200 people in Africa should be receiving palliative care each year (4). Nevertheless, palliative care access and services remain incredibly varied across the continent. The Republic of Botswana is one of 74 countries worldwide considered to have “isolated palliative care provision” (1). Originating in the wake of the country’s HIV/AIDS epidemic, palliative care in Botswana has grown alongside increased awareness and attention to the pressing need for palliative care services. The movement has made significant strides over the past decade in the spheres of policy, education and clinical implementation. Yet, the need for palliative care within the country is only growing, as Botswana continues to face a HIV/AIDS prevalence rate of 18.5%, equating to over 390,000 individuals living with the disease (5).

Minimal research exists evaluating the current status of palliative care in Botswana. This paper seeks to provide such a needs assessment, analyzing not only the existing infrastructure for palliative care delivery, but also the ongoing challenges that palliative care development faces.

Methods

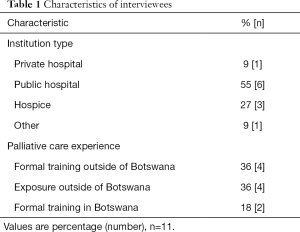

Data was collected from interviews conducted in Botswana in June and July 2015. Participants included physicians, nurses and hospice staff (Table 1). They were initially recruited through literature review, institutional and organizational websites, and in-person interactions. Subsequent participants were identified through snowball sampling, whereby interviewees suggested additional individuals. The iPhone application Voice Record Pro was used to record 6 out of 11 interviews. All interviews were transcribed by the author. Given that this study involved neither direct patient interaction nor patient protected health information, it was deemed exempt from ethics approval and institutional review board review.

Full table

Results

Palliative care delivery

Adult care

National dissemination of palliative care remains a significant hurdle for palliative care expansion in Botswana. Although the northern region of the country has access to palliative care services, these are limited, and the majority of services are available in the south, where palliative care is more established. The presence of the country’s only three hospices and sole palliative care physician have given Gaborone and the surrounding area greater access to care.

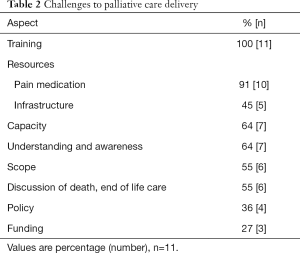

Princess Marina Hospital (PMH), the main referral hospital, along with the three hospices and home based care programs are the primary routes through which palliative care is delivered in this region. Within PMH, palliative care is largely confined to the oncology ward, as such services have not yet implemented hospital-wide. In collaboration with the oncology department, the country’s first palliative care clinic was established in 2015. Held once per week, this clinic serves patients who move through the oncology service. Yet, limited administrative scope restricts follow-up, while the volume of patients has hindered expansion beyond oncology. Sixty four percent (n=7) of those interviewed cited insufficient capacity in both workforce volume and infrastructure as a significant barrier to the delivery of palliative care in Botswana (Table 2). Across care settings, those trained in or familiar with palliative care face a growing need that frequently prevents them from providing care to both the extent and the number of patients that they would like to.

Full table

Pediatric care

Pediatric palliative care faces a similar challenge. The Botswana-Baylor Clinical Center of Excellence in Gaborone provides a significant portion of the country’s pediatric care. Originally founded in 2003 to treat children infected with HIV, the clinic has since expanded to include pediatric oncology patients. As the country’s only pediatric oncology program, the clinic stands as a unique, centralized model. This structure enables close follow-up, facilitated by a 24/7 telephone hotline available to patients and their families; yet, the ratio of trained pediatric oncologists to patient numbers continues to demand significant commitment from the clinic’s staff.

Hospice care

Outside of the hospital system, Holy Cross Hospice, Pabalelong Hospice and the hospice at Bamalete Lutheran Hospital have driven palliative care development. In Gaborone, a multidisciplinary team of 13 staffs Holy Cross Hospice, which provides a day care program, as well as home based care, and is currently working to open a newly constructed inpatient unit. Roughly 10 miles north, Pabalelong Hospice functions primarily as an inpatient center, offering 24-hour care to patients with terminal illnesses or in need of respite care, and supporting a maximum number of 10 patients through a similarly multidisciplinary team. Moreover, the hospice recently restarted its home care program in several nearby villages. Approximately 25 miles west, in Ramotswa, is the country’s third hospice, which exists within Bamalete Lutheran Hospital. Bamalete Lutheran Hospital is primarily a mission hospital, though it is partially staffed by government employees. Formed in 2013, the hospice operates through an interdisciplinary team. With nurses as the primary caregivers, the hospice serves largely oncology patients in a day care setting as well as through home visits. Referrals from oncology, in addition to local clinics and the community comprise the majority of the hospice patient population.

Home based care

Home based care programs are additionally meeting palliative care needs within the country. In Gaborone, local patients are able to access hospice services, but individuals traveling from greater distances are frequently referred to local clinics, and subsequently, to home based care. While most acknowledged that palliative care should be available to patients in any setting, 45% (n=5) of interviewees felt that home is an ideal site for palliative care delivery. One participant spoke to the widespread belief that many patients wish to die close to or at home. Nevertheless, home based care is confronting obstacles parallel to those present in other sectors of the health care system. Forty five percent (n=5) of those interviewed expressed concern for the provision of palliative care within home based care, citing capacity, training and infrastructural challenges such as transportation as predominant barriers to achieving the full potential of this delivery model.

Palliative care training

The limited number of palliative care health care workers in Botswana continues to restrict care throughout the country. Training is currently acquired in three ways: through the government, internally and internationally.

Government associated training

Acknowledging the increasing need for palliative care services, the government has worked to improve palliative care through strategic planning, training guides, and curricular development (6). In March of 2005, the Ministry of Health formed a partnership with the African Palliative Care Association (APCA), a dominant palliative care organization on the continent, committed to supporting African nations in creating palliative care services, policy and training. In June of that year, this collaboration led to the country’s first national palliative care training, primarily for nurses, followed by its first palliative care training package (7). Forming a partnership with the Institute of Health Sciences in Gaborone (IHSG) in 2007, APCA further began to assist the country in addressing capacity building (8), hoping to create wider and more comprehensive dissemination of palliative care awareness and education among those in the healthcare system (7). A subsequent partnership with the University of Botswana in 2010, has led to an introduction to palliative care course for 22 lecturers within the School of Nursing and Department of Social Work at the University. IHSG had included 40 hours of palliative care within their teaching programs, and 90% of Botswana’s higher education institutions have now been “oriented to palliative care” (9). APCA continues to support palliative care education efforts in Botswana, helping 157 individuals, including students, lecturers and healthcare workers, receive training from 2013 to 2014 through the Ministry of Health’s training package (10,11).

Internal and international training

For the country’s hospices and pediatric oncology program, training is largely conducted internally. In the case of Pabalelong Hospice, it has been through a partnership with the Hospice and Palliative Care Association of South Africa. Furthermore, while workshops and institutional coursework have been created, many of the current health care workers involved in palliative care received their training outside of Botswana. Thirty six percent (n=4) of those interviewed received formal palliative care training outside of Botswana, while an additional 36% (n=4) were exposed to the field outside the country and only 18% (n=2) have received formal training domestically.

Although training programs and initiatives have grown steadily and successfully in recent years, 100% (n=11) of participants commented on the need for more development and the barrier that insufficient training creates for palliative care expansion.

Policy development

Through its partnership with APCA and its growing investment in palliative care, the Ministry of Health completed a 5-year National Palliative Care Strategy stretching from 2013 to 2018. This plan advocates for palliative care to “be delivered as a continuum” by linking hospitals and clinics to community home based care programs. Although the document speaks of shifting palliative care into patient homes, it does not ignore the reality that palliative services in such home based programs are currently inadequate.

Despite being a significant achievement for the palliative care movement, the strategic plan has not been without criticism. A general need for more palliative care policies exists within the palliative care community, as illustrated by 36% (n=4) of those interviewed. However, a developing National Hospice and Palliative Care Policy stands to address many of these challenges, as well as others currently impeding palliative care growth. Associated with this focused effort to strengthen palliative care has been the involvement of the Botswana Hospice and Palliative Care Association (BHPCA), which launched in July of 2014. Providing an overarching organization for palliative care within the country, BHPCA has become an integral collaborator in the Ministry of Health’s palliative care agenda.

Ongoing challenges

The context within which palliative care is developing and the limited resources available for its delivery, define the primary barriers to palliative care growth that Botswana is facing.

Patient and health care provider awareness

Fifty five percent (n=6) of interviewees spoke to the difficulty of navigating the reluctance of many patients and families to discuss death and end of life care. This hesitancy forms an inherent obstacle to national palliative care development. Additionally, palliative care in Botswana faces a widespread lack of understanding and awareness. Sixty four percent (n=7) of participants identified this disconnect as a prominent challenge, expressing the difficulty of defining palliative care for patients, particularly during translation from English to Setswana. Moreover, the medical community is not immune to the need for increased awareness. Several interviewees commented that many health care professionals themselves misunderstand the role that palliative care plays, further impeding successful dissemination.

Human resources and funding

Combined with these contextual challenges is a pressing need for resources, primarily in the areas of human resources and funding. Forty five percent (n=5) of those interviewed felt that infrastructure limitations are challenging the ability to accommodate the volume of patients seeking care. Beyond this structural shortage is a lack of providers, stemming largely from the need for increased training. Funding limitations have further impeded palliative care progress, with 27% (n=3) of participants describing the subsequent impact on training and multiple levels of care provided at the country’s hospices. Because Holy Cross Hospice and Pabalelong Hospice are not government run or recognized, they rely almost exclusively on donations to function. This constraint stresses operations and hinders care capacity.

Access to pain medication

An adequate supply of and access to pain medications are also dominant issues in palliative care delivery. In 2013, APCA assisted the Ministry of Health in adapting the organization’s “Beating Pain” pain management guidelines (11). As a result, in 2014, the Ministry of Health and Center for Disease Control published the Botswana Pain Management Guidelines, entitled “Raga Ditlhabi”. Nevertheless, morphine shortages remain a reality and only physicians are able to prescribe morphine, despite ongoing discussion of lifting this barrier for nurses. Ninety one percent (n=10) of those interviewed expressed the need for continued improvement of pain medication provision.

Discussion

Structural limitations and the need for a greater number of palliative care trained health care workers continue to challenge palliative care development in Botswana, leading to a narrow scope of coverage, as expressed by 55% (n=6) of interviewees. Yet, Botswana is not alone in managing the difficulties of establishing palliative care in the developing world. For example, palliative care in India similarly faces the challenge of increasing palliative care access throughout the country. In India, 6 million people per year are in need of palliative care (12), and like Botswana, services are primarily concentrated in one region. Kerala provides 90% of the country’s palliative care despite containing only 3% of Indian’s population (13). Despite this geographic restriction, Kerala’s palliative care delivery has been well received since gaining momentum in 2007. The success of Kerala’s model can largely be attributed to its beneficial combination of government and community support. Community involvement has become the backbone of delivery, while the local self-government institutions have worked to shape, guide and drive the program (13).

This partnership speaks to a more widespread understanding of palliative care and awareness of need—a goal that Botswana is working towards. The Kerala model suggests that in striving to increase such understanding, Botswana has the potential to significantly enhance the current state of palliative care in the country. Moreover, Indian’s CanSupport, a local non-governmental organization, provides a model for successful palliative care delivery at home. Founded in 1997 and based in Delhi, CanSupport provides effective home-based palliative care services through multidisciplinary teams that make home visits and operate a 24/7 telephone hotline (14). Given the sentiment among 45% (n=5) of participants that care should be optimized in the home, the success of CanSupport in India suggests that targeting and addressing the current barriers within Botswana’s home-based care programs could play a role in advancing palliative care development throughout the country.

Over the past decade, Botswana has worked closely with Uganda-based APCA and several health care workers trained in palliative care have traveled to Uganda for instruction. Hospice Africa Uganda’s Institute of Palliative Medicine in Africa offers diploma courses at Makerere University. Uganda is the only African country deemed to have reached an advanced stage of palliative care integration into mainstream healthcare delivery (1). A national palliative care policy is currently in the process of being ratified (11), and coupled with policy development are Uganda’s efforts to enhance palliative care awareness. In 2014, the Uganda Broadcasting Corporation carved out airtime dedicated to describing what palliative care is, and how and where to receive it. Moreover, Uganda has succeeded in legalizing prescriptions for morphine by nurses. These achievements illustrate the potential for successful palliative care development in Africa.

In 2012, the Diana, Princess of Wales Memorial fund conducted several case studies assessing various palliative care delivery models in several African nations. This analysis highlights that the success of these models is rooted in the establishment of sufficient palliative care training, and functional partnerships connecting local and national health systems. What set some models apart from others were efforts to increase palliative care awareness and understanding, to gain reliable access to pain medications, and to focus on capacity building in order to provide consistent care to patients (15). Botswana is actively engaged at each of these levels in its work to improve palliative care within the country.

The reality of the unmet need for palliative care in Botswana is driving these efforts at an individual and organizational level. Furthermore, the number of patients who would benefit from palliative care is only growing. Enhancing awareness and comprehension of palliative care will be essential in responding to this increasing demand. For those involved in the country’s palliative care development, education and the strengthening of delivery structures will need to be cornerstones in moving forward.

Presenting the existing modes of care delivery through hospital, hospice and home based services, this paper provides an assessment of the current state of palliative care in Botswana. Limited understanding, structural instability, and the need for increased capacity through training present ongoing barriers. Yet, continued efforts by palliative care advocates are now being matched at the government level through policy achievements. The 2013 Botswana National Palliative Care Strategy and the emerging National Hospice and Palliative Care Policy are significant milestones for the palliative care movement. Directing attention towards and providing action plans for these various hurdles, these documents offer the potential to support Botswana in mirroring the success of other developing countries in establishing palliative care.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the Botswana Hospice and Palliative Care Association (BHPCA), Holy Cross Hospice and Hospice at Home at the Bamalete Lutheran Hospital for their support of and contributions to this project.

Footnote

Conflicts of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- Connor SR, Bermedo MC. Global Atlas of Palliative Care at the End of Life. 2014.

- Morris C. Palliative Care and Access to Medications for Pain Treatment. Cancer Control 2013.

- Global Health 2010;6:5. Tackling Africa's chronic disease burden: from the local to the global. Global Health 2010;6:5. [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. A Community Health Approach to Palliative Care for HIV/AIDS and Cancer Patients. 2004.

- National AIDS Coordinating Agency R of B. Progress Report of the National Response to the 2011 Declaration of Commitments on HIV and AIDS. 2015.

- Department of HIV/AIDS Prevention and Care, Ministry of Health R of B. Botswana National Palliative Care Strategy 2013-2018. 2013.

- African Palliative Care Association. Overview of APCA’s Work in Botswana, 2015.

- African Palliative Care Association. Annual Report 2009-2010. 2010.

- Anon. Palliative care: An essential part of medical and nursing training. Available online: http://kehpca.org/wp-content/uploads/education%20conference.pdf

- African Palliative Care Association. Annual Report 2011-2012. 2012.

- African Palliation Care Association. Annual Report 2013-2014. 2014.

- Khosla D, Patel FD, Sharma SC. Palliative care in India: current progress and future needs. Indian J Palliat Care 2012;18:149-54. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kumar S. Models of delivering palliative and end-of-life care in India. Curr Opin Support Palliat Care 2013;7:216-22. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- McDermott E, Selman L, Wright M, et al. Hospice and palliative care development in India: a multimethod review of services and experiences. J Pain Symptom Manage 2008;35:583-93. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Dix O, Ross-Gakava L. Models of delivering palliative care in sub-Saharan Africa: Advocacy summary. Available online: https://docplayer.net/60833430-Models-of-delivering-palliative-care-in-sub-saharan-africa-advocacy-summary.html