The use of Do-Not-Resuscitate-Order equivalents in pediatric palliative care medicine in Germany

Introduction

In 2013, 4,126 children and adolescents below the age of 20 years died in Germany due to diseases (accidents and sudden infant death syndrome are excluded) (1). The growing awareness that a majority of these children may be eligible for pediatric palliative care is mirrored in the fact that there is a legal claim of German patients for specific pediatric palliative care since 2007 which is funded by the national health care system (2). Although there is a law for advance health care directives for adults since 2009 (3) a legally valid standard reference for minors is still not available in Germany. The judicial conception in Germany in this matter still appears quite diverse: on one hand a minor is entitled to agree to or to refuse a medical intervention or investigation if his/her mental maturity is sufficient to judge on the relevance and consequence of his/her acting (4); on the other hand, even if a minor is mature and can obviously determine the relevance and consequence of his/her acting, there is no possibility for a legally valid advance healthcare directive that determines procedures and limitations of medical assistance in a palliative setting (3). In the legal situation in Germany at the age of 18 maturity is generally judged to be granted, but with younger patients there is no defined age when children should be sufficiently able to evaluate their decisions regarding consequences of his/her actions. The decision is done as the case arises.

In a statement of the Commission for Ethical Issues of the German Academy for Pediatric and Adolescent Medicine, it is recommended that advance healthcare directives of minors (age below 18 years) should be usually respected assuming that the minor is obviously competent to consent (in clinical trials, in the treatment of oncological diseases, for serious illnesses or for major surgery all adolescents older than 16 years have to agree), and the consenting doctor explains all possible outcomes and risks associated with the relevant therapeutic and diagnostic interventions and procedures (5).

In case of younger children or children and adolescents without sufficient competence to determine medical decisions, parents or a person having the custody of the child may consent to advance healthcare directives. If the best interest of the child and adolescent is kept (Grundgesetz der Bundesrepublik Deutschland, German Constitution, Art. 6) (6); this may also include medical decisions at the end of life. However, it is also common sense in Germany that it should be always aimed at finding a consensus between parents and attending doctors about the aim of therapy and life-sustaining procedures (7).

Nevertheless, in Germany there is still to date no lawfulness for advance directives by children or parents. Any consented advance healthcare directive by parents or legal representatives are legally not binding for the treating physicians.

In 2009, Rellensmann and Hasan published a standard form to define therapeutic and diagnostic measures for pediatric patients with life limiting diseases in case of emergencies (8). This form had been critically reviewed and accepted by several pediatric medical societies. Although this form may be on first sight similar to a Do-Not-Resuscitate-Order (DNR-Order) in adult patients, the actual impact of this document is totally different: (I) the document is not explicitly designated as a DNR-Order, its title is “Recommendations for procedures in case of emergencies”; (II) only a doctor and a nurse have to sign, no parents or patients. Furthermore, this document is not legally binding but it represents an acceptable and honourable approach to give some kind of orientation in the yet unclarified situation of advance healthcare directives for children and adolescents in Germany.

In the present study, we aimed at investigating the acceptance and usage of such DNR-order-like forms and documents such as the “Recommendations for procedures in case of emergencies” by Rellensmann and Hasan (8) by different institutions and groups involved in palliative care of pediatric oncology patients in Germany. Furthermore, we asked about missing and/or improvable aspects in the currently used DNR-order-like documents.

Methods

For the present study, a questionnaire was sent between August 2012 and October 2013 to the following 174 institutions and groups which were involved in the palliative care of pediatric oncology patients in Germany: 42 pediatric oncology centers, 11 children’s hospices, 97 out-patients children’s hospice services, and 24 teams providing specialized palliative out-patient care for children (SAPPV = Spezialisierte ambulante pädiatrische Palliativversorgung). These institutions and groups were identified via the German Children’s Hospice Association in June 2012 and a list of German pediatric oncology centres obtained via the University Children’s Hospital of Halle, Halle, Germany, in April 2012.

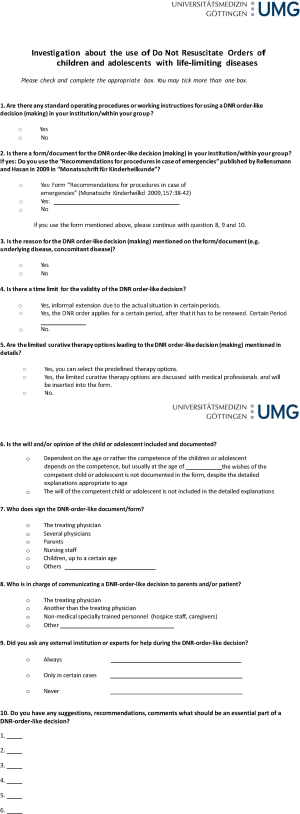

The questionnaire consisted of 10 items as shown in Document S1. The original questionnaire that was sent was in German language.

Results

The response rate to our questionnaire was 70.7%, i.e., 123 of 174 institutions took part in the present study. Some of the responding organisations answered with written letters, emails, by telephone or fax. 82/174 (47.1%) did not respond to all questions of the questionnaire as determined, they were included the same as those who respond to all questions.

Responses to the questionnaire were divided among the different institutions and groups as follows: 7/11 children’s hospices (63.3%), 51/97 outpatient’s children’s hospice services (52.6%), 13/24 teams providing specialized palliative out-patient care for children (SAPPV teams) (54.2%), and 21/42 pediatric oncology centers (50%). 31 institutions and/or groups answered anonymously and could not be allocated.

The first item was answered by 99 institutions/groups. Fifty-nine institutions (59.6%) declared that they use standard operating procedures, instructions, or guidelines to discuss and/or decide on limitation of therapeutic options within a palliative setting.

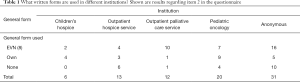

Eighty-two institutions reported on the type of printed form they were using for DNR-order-like decision making (item 2) (Table 1). Most institutions (n=39; 47.6%) used the form which is recommended by various pediatric societies [Rellensmann and Hasan, 2009 (8)]. This form is entitled as “Empfehlungen zum Vorgehen in Notfallsituationen” (EVN; English title: “Recommendations how to proceed in medical emergencies”). Interestingly, this form was used by the majority of the German pediatric networks for specialized palliative out-patient care (10/12; 83.3%). On the contrary, 22 of all institutions (26.8%) used their own, individualized forms for limiting treatment options, among them nine (45.0%) pediatric oncology centers. Twenty-one (25.6%) institutions/groups did not use any specified form or no form at all. Six (28.6%) of these institutions were out-patients children’s hospice services which might not routinely be involved in decisions on treatment limitations, but still four (19.0%) pediatric oncology centers and one (4.8%) network for specialized palliative out-patient care were also among the institutions without a general form to limit therapeutic options in case of a life limiting disease (Table 1). Ten (47.6%) institutions without any specified form for treatment limitation answered anonymously and could not be assigned to an institutional category.

Full table

As third item, it was asked whether the underlying life limiting disease is explicitly mentioned in the specified form on limiting therapeutic options in case of emergency. This was confirmed by 60 (83.3%) institutions, but 12 (16.7%) institutions did not routinely mention the underlying life limiting condition.

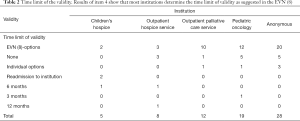

Item 4 was about a time limit for the validity of the DNR-Order and was answered by 72 institutions. In 58/72 (80.6%) institutions, there is usually a time limit for the validity of treatment limitation, in 14/72 (19.4%) institutions there is not. The time limit varied within the different forms: in 47/72 (65.3%) of specialized forms, there was a choice between 1 week, 1 month, 3 months, or 6 months, whereas in 5/72 (6.9%) institutions the time limit of validity of the DNR-order-like document was determined individually (Table 2).

Full table

Regarding item 5, the choices of therapeutic options which may be limited were studied in the various forms. 71 institutions replied to this item. 38/71 (53.5%) institutions use specified forms in which therapeutic options can be marked with a cross but which also provide additional space for individual annotations. 16/71 (22.5%) institutions/groups insert the therapeutic options to be limited or not limited as free text. In 14/71 (19.7%) institutions/groups, there are only different specified options to choose without the possibility for free text additions. In 3/71 institutions/groups specific therapeutic options which should be limited are not mentioned in particular.

Item 6 dealt with the patient’s (child’s) own intentions and wishes in regards to limitations of therapeutic options. 72 institutions answered to this item. 39/72 (54.2%) institutions/groups declared that the will of the patient is mentioned in dependence of the capacity his/her discernment. In 5/72 (6.9%) institutions, the will of the patient is documented in dependence of the age; suggestions for relevant age groups to document actively the patient’s will range from 12 to 16 years. 26/72 (36.1%) institutions answered that the will of the patient is documented when a standard form like the “Empfehlungen zum Vorgehen in Notfallsituationen” (EVN; English title: “Recommendations how to proceed in medical emergencies”) is used [Rellensmann and Hasan, 2009 (8)]. In 2/72 (2.8%) institutions the patient’s intention is not included in the general form for limitation of therapeutic options.

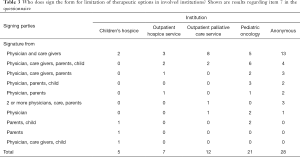

Item 7 was about who signs the form for limitation of therapeutic options (Table 3). In 31/73 (42.5%) institutions, the attending physician and nurse sign the form. In 14/73 (19.2%) institutions, the attending physician, nurses, parents, and patients all sign the DNR-order-like document. Other combinations of involved parties were attending physician/nurse/parents (n=6; 8.2%), attending physician/parents/patient (n=5; 6.8%), attending physician/parents (n=4; 5.5%), two or more physicians/nurse/parents (n=4; 5.5%), attending physician only (n=4; 5.5%), parents patient (n=3; 4.1%), parents only (n=1; 1.4%), and attending physician/nurse/patient (n=1; 1.4%).

Full table

In item 8, we asked how the talking about limiting therapeutic options is organized in the different institutions. 75 institutions replied to this question. In most cases, the attending physician is leading the talking (n=44; 58.7%). The second most frequent answer was that a specialized team including a physician (“therapeutic team”) conducts the talking (n=20; 26.7%). Other combinations were more than one physician involved (n=4; 5.3%), nursing staff only (n=3; 4.0%), physician and social worker/psychologist (n=2; 2.7%), physician and clinical ethics committee (n=1; 1.3%) and another physician different from the treating one (n=1; 1.3%).

Item 9 was about the consultation of external partners in regards to limiting therapeutic options. Most institutions (n=46/73; 63.0%) only involve extern partners (that are not part of the current treatment) in difficult cases; mostly the clinical ethics committee was involved (n=33/46; 71.7%). 25/73 (34.2%) institutions never asked for external support. Only in 2/73 (2.7%) institutions, extern counselors (clinical ethics committee) are consulted for each patient in regards to treatment limitations. In difficult cases, the family court was also involved in 2/46 (4.3%) institutions, a combination of local court and youth welfare office in 2/46 (4.3%), the administration of the hospital in 2/46 (4.3%) or an external physician specialized in palliative care in 1/46 (2.2%). Five (10.9%) institutions did not specifically indicate which external partners are involved for additional support.

For the last item, we asked about suggestions that should be part of a specified form for limitation of therapeutic options in children with life-limiting disease. We got 135 individual suggestions regarding essential contents of such a form. We summarized the different answers/suggestions in 4 categories.

The first category (n=64/135; 47.4%) contains proposals for the layout of such a specified form for treatment limitations. The most frequently suggested item was a check list with possible therapeutic options for medical emergencies (n=12; 18.8%) followed by contact details of the care team (n=10; 15.6%), a documentation of the time limit for the validity of the DNR-order-like document (n=8; 12.5%), and free text space for individual annotations (n=7; 10.9%). Six (n=6; 9.4%) suggestions confirmed the appropriateness of the DNR-order-like form [published by Rellensmann and Hasan, 2009 (8)].

The second category summarized all suggestions (n=15/135; 11.1%) in regards to the initial talking about limiting therapeutic options. Nine (n=9; 60%) stated that a protocol about the content of the initial talking is important. Two (n=2; 13.3%) felt that a handout with an explanation is important.

The third category was about suggestions regarding detailed information about the patient and his/her family (n=34/135; 25.2%). Half of the suggestions (n=17; 50%) focused on reporting the underlying disease and concomitant symptoms on the DNR-order-like form. Four other replies (n=4; 11.8%) suggested that possible symptoms and expected complications of the patient should be also stated.

The last category subsumed suggestions (n=22/135; 16.3%) for therapeutic procedures which may be limited in a palliative care setting. There is an obvious need for an algorithm in medical emergencies (e.g., “What to do if therapeutic options, for example pain treatment fails?”) (n=5; 22.7%). Another point was that the use of antibiotics should be also listed as a therapeutic option which may be limited in medical emergencies case within a palliative setting (n=4; 18.2%).

Other suggestions from each category are for better overview listed in supplemental Table S1.

Full table

Discussion

The aim of the present study was to find out how often and which DNR-order-like forms or advance directives for treatment limitations in children with life-limiting diseases are used in institutions that are involved in pediatric oncological palliative care in Germany. Although in Germany there is no lawfulness for such forms or directives with legal binding for the treating physicians, many of the contacted institutions use specified forms to determine medical procedures in palliative expected and unexpected situations. The form that is used by the majority of the institutions is the “Empfehlungen zum Vorgehen in Notfallsituationen” by Rellensmann and Hasan [2009] (EVN; English title: “Recommendations how to proceed in medical emergencies”) (8). Thus, the present study confirmed that there is an obvious need for a DNR-order-like document for children with life-limiting diseases.

This need is very interesting since the discussion about the legal facts of such a document in Germany appears endless and not solvable (5,9,10). The German law only allows a legally competent adult to report a final living will (3) but parents as the legal guardians for their children can decide whether a physician is allowed to treat their children or not, also in any palliative situation. This parental right is covered by the German constitution which claims that the care of children is the natural right of their parents (Grundgesetz für die Bundesrepublik Deutschland, Art. 6) (6). Only in case of endangering the well-being of the children a court can be interposed (11). Even more complicating, in emergency situation without a possibility for clarifying discussions the treating physicians has the final responsibility to decide if a child should be treated or not in regards to his/her quality of life and well-being.

Defining the endangerment of a child’s well-being within a palliative setting seems at least very difficult if not to say impossible. In this context, the medical indication or the potential futility of a certain therapeutic measure has to be evaluated. If the medical measure or treatment appears clearly futile to the physicians then it is forbidden to initiate this medical measure or treatment, even if the patient or the parents wish to do so (12). The aim of any treatment is to save life, but never to extend the deceasing by medical treatment if the additional time is not a benefit for the dying person (10). However, to judge on potential futility of a certain treatment in a palliative setting is very difficult, too.

Another very difficult aspect in regards to limiting treatment for a child within a palliative setting is how to consider and respect the opinion or even decision of a minor about his/her own medical treatment. Following the German law the minor always has a right to veto any treatment decision regarding him-/herself in case of his/her competence. This competence is not restricted to a certain age but has to be evaluated, e.g., by the treating physician that knows the patient and the situation very well (5). If the patient is then regarded as competent to decide on his/her medical treatment this should be documented. It would be of course advisable, too, that the conclusion on the minor patient’s competence and his/her will occur on any DNR-order-like document/advance directive used to limit treatment options in a palliative setting.

Many German institutions involved in palliative care of pediatric oncology patients use the conventional advance directive recommended by many German pediatric medical societies (Rellensmann, Hasan, 2009) (8) however, the present study reveals that there is a need for improvement of this form. Especially the place for individualizing the form and to supplement a special emergency plan seem to be insufficient. Furthermore, potentially limitable therapeutic measures may be added.

Documentation of end of life decisions in pediatrics appears in general especially difficult, independently of the setting (pediatric intensive care versus pediatric oncology) or a certain country (13-16). However, as also shown in our study, a printed form of a DNR-order-like document is usually preferred to a handwritten protocol. With a more or less standardized printed form the degree of documentation of the end-of-life decisions can be improved (17). The widely used standardized German form [Rellensmann and Hasan 2009 (8)] was developed for medical staff who do not know the child and will, therefore, need a quick overview in case of a medical emergency (8). This seems as the most important function of such a DNR-order-like document because the treating (palliative care) team usually knows about the patient’s condition and knows the parents as well as their will in regards to the treatment options for their child with a life limiting disease. The need of a DNR-order-like form is necessary for situations when there is no direct involved person of the treating team in touch with unexpected events of the patient. And when a standardized printed form is already well known and accepted within the medical community then it is easier for a physician to decide on treatment measures when he/she is involved in an emergency situation of an unknown child within a supposedly palliative setting (17). The physician will need in an emergency situation of a pediatric palliative care patient a summarized overview about the current status regarding disease, prognosis, and possible treatment limitations without long talks, discussions and text descriptions. Even if the parents of the patient would never call an emergency physician in any expected or unexpected palliative situation other witnesses of unexpected situations might do so because they might not know about the special situation. And quite often parents still call the emergency physician themselves in spite of good ongoing care and intensive upfront preparations towards such emergency situations by the palliative care team. Any such preparation of parents about the palliative situation of their child and possible events cannot really prime them for the actual high emotional and most painful situation when their child will probably die. For those cases, a DNR-order-like document could remind parents of previous decisions they had made without the high emotional stress of the current emergency situation (18).

Given this important aspect of such a DNR-order-like form, it is essential to reflect which information has to be included in such a document. It seems obvious that this form should be as short as possible, but nevertheless still highly informative. This was a common demand by many institutions involved in the present study. It was commented that the respective addressee of such DNR-order-like forms should always get all important information, even if this information may have to cover several years. These suggestions make it impossible to restrict such a DNR-order-like form to one page. Actually, only one institution involved in the present study intended for a printed form on one page. This interesting observation of a majority asking for more detailed information about the patient’s current situation appears to be in clear contrast to the aim of presenting a short, concise overview in emergency situations to physicians who do not know the patient. This observation may reflect another important aspect of such a DNR-order-like document, i.e., a protocol and “official” representative and explaining summary of end-of-life decisions which are not infrequently the results of long and intensive discussions between the parents and the palliative care teams. Deciding on treatment limitations in a palliative situation is often not a quick, clear process at the end of a single talk between the involved parties it is much more frequently a slow dynamic process over numerous talks and discussions. Thus, the decision to limit treatment options in a palliative care situation for a child with a life limiting disease is also the expression of a long communicative process between the parents and the palliative care team. Especially for the palliative care team, such a document then certainly has a higher importance then just providing a quick, concise overview about the patient’s current situation. The widely used form by Rellensmann and Hasan (8) tried to find a compromise between these two positions by limiting the DNR-order-like document by one page but requesting an additional protocol of the talk which resulted in the treatment limitation but the present study shows that this on first sight practical compromise is obviously not widely accepted or in use.

In this respect, the phone number of the treating physician or palliative care physician which should be available at all time appears essential. Permanent availability of the treating physicians is not only very important for the parents but also for any emergency physician that does not know the pediatric palliative care patient. Thus, the emergency physician can always call to get a quick, concise overview by phone.

In the present study, it was also suggested by many institutions to insert an emergency plan into the DNR-order-like document that deals with the potentially needed individualized measures of the specific patient in case of symptoms not restricted to medical emergencies. Thus, a mixture of a symptom control plan and limitation of therapeutic measures was requested. On first sight, this request seems as mixing up two different and independent intentions but at a closer look this might be the expression of a high uncertainty of palliative care teams to decide between a necessary and helpful therapeutic measure and a futile one. In case of pain, this decision seems obvious and easy, but e.g., in case of infections the use of antibiotics might be more difficult to be judged as either futile or beneficial. Thus, an extended plan with regards to expected or unexpected symptoms could reduce stress and be helpful for the patient, the family, and—last but not least—the palliative care team (18).

In many palliative situations of oncology patients, most withdrawn medical treatments are chemotherapy, antibiotics, antimycotics, artificial nutrition, mechanical ventilation, and catecholamines (19). These findings are similar to Lantos and Berger et al. who reported chemotherapy, blood transfusion, catecholamines, and dialysis as frequently limited therapeutic measures (20). Some of these measures were also suggested in the present study. Thus, the extension of potentially limitable therapeutic measures may have to imply also the items antibiotics, blood products, artificial nutrition, dialysis, and mechanical ventilation. Nevertheless, in our own experience the wishes and views of patients and parents are very individual due to their personal experience and personal situation. It should, therefore, be enough space for personalized requests; this was also suggested by many institutions in the present study.

Another information that should be included in a DNR-order-like form might be whether the patient and the family wish to be hospitalized or not at end of life. Many patients are dying in the intensive care unit or in hospital (21,22) but many people wish to die at home, this includes also terminally-ill children and their families (23). Thus, it appears necessary to decide before the occurrence of medical emergencies if the child should be transferred to a hospital or stay at home at end of life.

The German Federal Ministry of Justice also advises to note attendance for organ donation in case of death (24). Although pediatric oncology patients are usually excluded from organ donation because of their underlying disease this should also be discussed upfront with parents and—if possible—also with patients. This information may also occur on a DNR-order-like form for pediatric palliative care patients. The same may also apply to the information if an autopsy should be performed or not. Autopsy might be particularly helpful for parents after the death of their child (25).

We also asked in the present study who signs a DNR-order-like document for children with a life limiting disease. Not very surprisingly, most institutions indicated that the treating physician and the involved care team sign in most cases like it is recommended in the existing printed form from Rellensmann and Hasan (8). Only in some cases, the parents and/or the patient also sign the DNR-order-like document. This exclusivity of medical staff to sign the document on potential treatment limitations reflects that the involved physician always has to decide on the indication and performance of any treatment measures (11,26,27). Hence, it is always necessary to have a DNR-order-like form signed at least by a physician; this is different to advanced directives of adult patients to limit treatment options. However, as already reported in the introduction it is always important to document that the decisions made on limiting treatment option for a child in a palliative care situation are also supported and shared by parents and also by the minor patient (28). Nevertheless, for parents it is often a burden to make such decisions for their children (29). They could feel like signing the kid’s death sentence (9). Therefore, it is not sensible to force parents (or patients) to sign the treatment limitations. Parents (and the patient, in case of competence) should always have the possibility to sign a DNR-order-like form but their signature should not be mandatory.

Conclusions

Our study has several limitations. First we did not test the questionnaire upfront in a smaller cohort to test for ambiguous questions. Furthermore, we included every returned questionnaire in the study, also incomplete and anonymous questionnaires were entered into the present analysis. Thus, not every item is represented within all returned questionnaires, and not every item could be allocated to a certain category of palliative care providers for pediatric oncology patients. We also included institutions like out-patients children hospice services in our survey although we had to realize upon getting the replies that these institutions are nearly never involved in end of life decisions of their patients which is interesting information by itself. Last but not least the present study was performed in Germany and may, therefore, only reflect the medical, ethical, psychosocial, and legal situation in Germany.

One general limitation of such investigations like the present one which are based on a questionnaire is that we do not know who actually replied to the questionnaire and if the reply of this person indeed represents the situation/opinion of the respective institution/team. Thus, a certain subjective bias with the risk of a personal interpretation of the actual situation/team opinion cannot be fully excluded.

Nevertheless, a DNR-order-like form for terminally-ill children appears absolutely necessary. The present study revealed that there are numerous suggestions to modify and extend the widely used document by Rellensmann and Hasan [2009] (8). Obviously, many institutions have already adjusted this printed form to their own clinical practice. It would be advisable to set up new versions of this DNR-order-like document based on these experiences and test the different versions in a prospective study. In the end every physician has to decide whether he prefers to use a pre-developed printed form or an individualized form for his/her patients. Treatment requests or their limitations by parents and patients are to be respected, but they are not legally binding which will always create a lot of uncertainty and emotions between the involved parties. Thus, the best strategy and documentation for DNR-order-like decisions are still to be found.

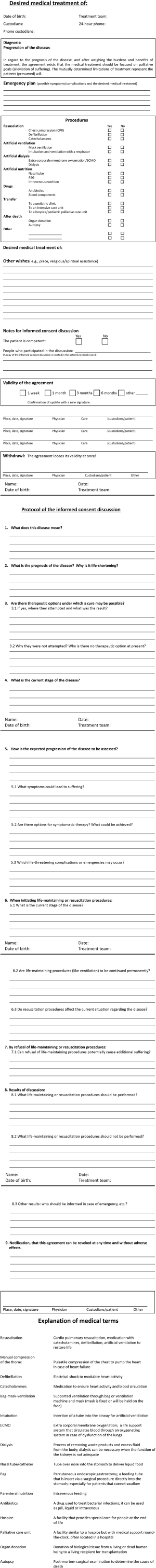

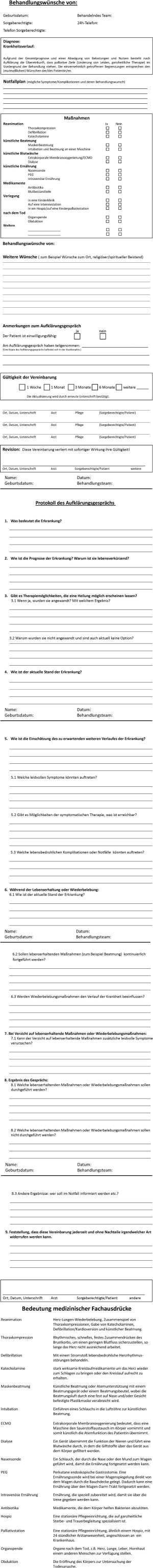

As result of our work we suggest a new form of a DNR-order-like decision, including a protocol of agreement with explanation of medical terms (Document S2: English, Document S3: German).

Document S1 Original questionnaire of the survey (translated into English)

Document S2 Our suggestion for a new DNR-order-like decision document including protocol of agreement with explanation of medical terms (English)

Document S3 Our suggestion for a new DNR-order-like decision document including protocol of agreement with explanation of medical terms (German)

Acknowledgements

None.

Footnote

Conflicts of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: For our study, ethics approval was not required because no patient data or personal data of any other human being was neither investigated nor collected. In addition, no harmful intervention was performed to any individual. The aim of our study was to get an overview how the various institutions and teams involved in pediatric palliative care in Germany deals with DNR-order-like issues.

References

- Federal Statistical Office Germany (Statistisches Bundesamt), Fachserie 12, Reihe 4, Jahrbuch 2013; Gesundheit; Todesursachen in Deutschland.

- German law: Sozialgesetzbuch (SGB) Fünftes Buch (V) - Gesetzliche Krankenversicherung - (Artikel 1 des Gesetzes v. 20. Dezember 1988, BGBl. I S. 2477) § 37b Spezialisierte ambulante Palliativversorgung.

- German law: Bürgerliches Gesetzbuch (BGB), § 1901a Patientenverfügung.

- Adjudication: BGH Urt. v. 05. Dezember 1958 - VI ZR 266/57, BGHZ 29, 335. Available online: https://www.uni-trier.de/fileadmin/fb5/prof/BRZIPR/urt/bgbat/bgbat80.pdf

- Kommission für ethische Fragen der Deutschen Akademie für Kinder- und Jugendmedizin. Patientenverfügungen von Minderjährigen. Monatsschr Kinderheilkd 2015;163:375-8. [Crossref]

- German law: Grundgesetz für die Bundesrepublik Deutschland. Art. 6

- Führer M, Duroux A, Jox RJ, et al. Treatment decisions for severely ill children and adolescents. MMW Fortschr Med 2011;153:35-6, 38. [PubMed]

- Rellensmann G, Hasan C. Empfehlungen zum Vorgehen in Notfallsituationen. Monatsschr Kinderheilkd 2009;157:38. [Crossref]

- Jox RJ, Führer M, Borasio GD. Patientenverfügung und Elternverfügung. Monatsschr Kinderheilkd 2009;157:26-32. [Crossref]

- Putz W, Steldinger B. Rechtliche Aspekte der Therapiebegrenzung in der Pädiatrie. Monatsschr Kinderheilkd 2009;157:33-7. [Crossref]

- Bundesärztekammer. Grundsätze der Bundesärztekammer zur ärztlichen Sterbebegleitung. Dtsch Arztebl 2011;107:A877-82.

- Mercurio MR, Murray PD, Gross I. Unilateral pediatric "do not attempt resuscitation" orders: the pros, the cons, and a proposed approach. Pediatrics 2014;133 Suppl 1:S37-43. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Devictor DJ, Nguyen DT. Groupe Francophone de Réanimation et d'Urgences Pédiatriques. Forgoing life-sustaining treatments: how the decision is made in French pediatric intensive care units. Crit Care Med 2011;29:1356-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hinds PS, Oakes LL, Hicks J, et al. Parent-clinician communication intervention during end-of-life decision making for children with incurable cancer. J Palliat Med 2012;15:916-22. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Sprung CL, Woodcock T, Sjokvist P, et al. Reasons, considerations, difficulties and documentation of end-of-life decisions in European intensive care units: the ETHICUS Study. Intensive Care Med 2008;34:271-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Stark Z, Hynson J, Forrester M. Discussing withholding and withdrawing of life-sustaining medical treatment in paediatric inpatients: audit of current practice. J Paediatr Child Health 2008;44:399-403. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Mittelberger JA. Impact of a Procedure-Specific Do Not Resuscitate Order Form on Documentation of Do Not Resuscitate Orders. Arch Intern Med 1993;153:228-32. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Postovsky S, Ben Arush MW. Care of a child dying of cancer: the role of the palliative care team in pediatric oncology. Pediatr Hematol Oncol 2004;21:67-76. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Baker JN, Kane JR, Rai S, et al. Changes in medical care at a pediatric oncology referral center after placement of a do-not-resuscitate order. J Palliat Med 2010;13:1349-52. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lantos JD, Berger AC, Zucker AR. Do-not-resuscitate orders in a children's hospital. Crit Care Med 1993;21:52-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Drake R, Frost J, Collins JJ. The symptoms of dying children. J Pain Symptom Manage 2003;26:594-603. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Klopfenstein KJ, Hutchison C, Clark C, et al. Variables influencing end-of-life care in children and adolescents with cancer. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol 2001;23:481-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hinds PS, Drew D, Oakes LL, et al. End-of-life care preferences of pediatric patients with cancer. J Clin Oncol 2005;23:9146-54. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bundesinisterium der Justiz und für Verbraucherschutz: Patientenverfügung. Leiden-Krankheit-Sterben. Hg. v. Bundesinisterium der Justiz und für Verbraucherschutz und Referat Öffentlichkeitsarbeit. 2014 Berlin. Available online: http://www.bmjv.de.

- Laing IA. Conflict resolution in end-of-life decisions in the neonatal unit. Semin Fetal Neonatal Med 2013;18:83-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Deutsche Gesellschaft für Medizinrecht. Einbecker Empfehlungen der Deutschen Gesellschaft für Medizinrecht zu den Grenzen der ärztlichen Behandlungspflicht bei schwerstgeschädigten Neugeborenen. 1992. MedR 1992, 206. Available online: https://www.leona-ev.de/index.php?eID=dumpFile&t=f&f=889&token=7b4ced21693e05177d52d829e24b04fedb232e48

- Kinderpalliativmedizin Führer M. Monatsschr Kinderheilkd 2011;159:583-96. [Crossref]

- Zernikow B. Palliativversorgung von Kindern, Jugendlichen und jungen Erwachsenen. Springer, Heidelberg, 2009.

- Pyke-Grimm KA, Degner L, Small A, et al. Preferences for participation in treatment decision making and information needs of parents of children with cancer: a pilot study. J Pediatr Oncol Nurs 1999;16:13-24. [Crossref] [PubMed]