Spiritual care as an integrated approach to palliative care for patients with neurodegenerative diseases and their caregivers: a literature review

Background

The United Nations (UN) and the World Health Organization (WHO) have stated that providing access to “palliative care is an ethical responsibility of health care systems, and that it is the ethical duty of health care professionals to alleviate pain and suffering, whether physical, psychosocial or spiritual, irrespective of whether the disease or condition can be cured, and the end-of-life care for individuals, is among the critical components of palliative care.” (1) According to the International Association for Hospice and Palliative Care (IAHPC):

- Palliative care is applicable throughout all health care settings (place of residence and institutions) and in all levels (primary to tertiary);

- Palliative care can be provided by professionals with basic palliative care training;

- Specialist palliative care with a multiprofessional team is required for referral of complex cases (2).

Across the world better, and earlier, integration of palliative care alongside active treatment is necessary (1) and this needs to be a global endeavor.

Modern palliative care can be provided alongside treatments targeting the underlying disease, and may be useful from the time of diagnosis (3-5). According to The Lancet Commission on Palliative Care and Pain Relief: “HIV and cancer cause the largest number of people experiencing serious health-related suffering.” (6) Nevertheless, in 2006, the WHO acknowledged that “the burden of neurological disorders has been seriously underestimated by traditional epidemiological and health statistical methods that take into account only mortality rates but not disability rates.” (7) Singhal et al. report that the neurological services and resources are disproportionately scarce, especially in low and middle-income countries. In rural areas, neurologic services are unavailable, and the overall lack of health insurance leads to out of pocket payments, making the existing services available for selected few. Therefore, large segments of the world’s population receive no treatment for epilepsy or other neurological conditions (8). For example, in Ghana, inadequate medical facilities, lack of stroke care protocols, limited staff numbers, inadequate staff development opportunities, and broader national health policy limits acute stroke care (9). Demographic transition has resulted in a significant increase in the elderly population, bringing to the fore degenerative neurological diseases such as stroke, Alzheimer’s disease, and Parkinson’s disease (8). According to the WHO, “the extension of life expectancy and ageing of populations globally predicts rise in the prevalence of neurological and other chronic disorders and the disability.” (7).

Patients with chronic neurodegenerative disorders suffer from the burden of disease progression without the hope for a cure. Therefore, symptom management and palliative care approaches should be included from the beginning of the illness until the death and beyond (10-18). The Lancet’s call for action specifies: “As the world population ages, comorbidity also increases. A shift from a health system centred in medical specialties to person-centred care is required.” (19). Hence, regular conversations with patients and their caregivers, alongside with well-designed screenings and assessments, are essential to prevent, detect, and manage possible unmet needs to diminish distress, fear and grief. For example, in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) patients and caregivers early and open discussion of end-of-life issues “allows time for reflection and planning, can obviate the introduction of unwanted interventions or procedures, can provide reassurance, and can alleviate fear.” (16). Currently, the global aspiration is that patients with chronic life-limiting conditions should be introduced to generalist palliative care and “referral for specialist palliative care support should be made at any time when physical, social, psychological, or spiritual unmet needs are not able to be satisfactorily resolved by the primary caring team” (3) even if the treatments are ongoing.

The WHO definition of palliative care suggests that palliative care addresses patient needs in the physical, social, psychological, and spiritual domains (3). The importance of palliative care for patients with progressive neurological diseases has been highlighted in The Lancet Neurology with the requirement for increased funding and research (20). A consensus review on the development of palliative care for patients with chronic and progressive neurological disease summarises that “within neurological disease there is limited evidence of the effectiveness of careful assessment and management of all aspects of care—physical, psychological, social and spiritual—as part of a palliative care approach” (12). Regarding the spiritual care as an integral part of palliative care Gofton et al. have identified three key challenges that shape and complicate palliative care for patients’ with MNDs:

- Uncertainty with respect to prognosis, support availability and disease trajectory;

- Inconsistency in information, attitudes and skills among care providers, care teams, caregivers and families;

- Existential distress specific to neurological disease, including emotional, psychological and spiritual distress resulting from loss of function, autonomy and death (21).

These complex challenges arise from the nature of the disease trajectory that radically affects the patient’s sense of self, challenges personal beliefs and relationships, and diminishes the feeling of belonging.

Spiritual dimension, spirituality and spiritual care—working definitions to begin with

In May 1984, the WHA resolution 37.13 made the spiritual dimension part and parcel of WHO Member States’ strategies for health (22). According to the WHO “The spiritual dimension is understood to imply a phenomenon that is not material in nature, but belongs to the realm of ideas, beliefs, values and ethics that have arisen in the minds and conscience of human beings, particularly ennobling ideas. […] The spiritual dimension plays a great role in motivating people’s achievement in all aspects of life.” (23). Hence, the spiritual dimension is an integral meaning-giving aspect of human existence, and thus, spiritual needs are universally experienced by healthcare professionals, patients and caregivers, particularly during critical and transformative life events (24). Accordingly, the spiritual field is multidimensional, containing:

- Existential challenges (e.g., questions concerning identity, meaning, suffering and death, guilt and shame, reconciliation and forgiveness, freedom and responsibility, hope and despair, love and joy);

- Value based considerations and attitudes (what is most important for each person, such as relations to oneself, family, friends, work, things, nature, art and culture, ethics and morals, and life itself);

- Religious considerations and foundations (faith, beliefs and practices, the relationship with God or the ultimate) (25).

While religious spirituality, in which religion provides identity, morals and faith in a higher power may be distinguished from secular spirituality, which emphasises on unity, integrity, holism and individuality, this European Association for Palliative Care (EAPC) definition comprises both (26,27).

Spiritual care is not a synonym for healthcare chaplaincy, it is not a burdensome addition on to normal care, spiritual care is openness towards spiritual dimension and acknowledges patients’ and caregivers’ needs, options, resources, civil rights and possible spiritual or religious limits. Spiritual care is tolerance towards patients’ and caregivers’ wish not to discuss spiritual needs and concerns with healthcare providers (24,28,29). Spiritual care in palliative care pays attention to spirituality via presence, empowerment and bringing peace (30).

Aim

In this literature based review article, we explore the state and status of spiritual care as an integrated palliative care approach for patients with neurological diseases and their caregivers. This is to prevent that the (self-)perceived lack of knowledge, time, and potential belief mismatch would not constitute barriers to the timely access and adequate spiritual care of patients and their caregivers (28,31) provided by neurologists, nurses, and allied healthcare staff, or/and in complex cases by a multiprofessional team of palliative care specialist. Essentially, addressing spirituality and providing spiritual care is a shared responsibility of physicians, nurses, psychotherapists, chaplains, and other health professionals (29). This article seeks answers to the following: what is known already and how to tap into spiritual dimension without causing false hopes or increasing vulnerability in patients with neurological diseases and their caregivers.

Methods

Evidence for this literature based review was obtained from a search of the PubMed, Web of Science and Google Scholar. Two independent scholars carried out the search from 12/2019 to 01/2020. The search was limited to past ten years (01/2010–01/2020) including articles containing words ‘spirituality; spiritual care; meaning; religion’ and ‘neurodegenerative diseases; brain localization; brain; motor neuron disease; Parkinson’s; glioblastoma; ALS; Alzheimer’s; and stroke’. We excluded articles that considered spirituality of multidisciplinary healthcare teams and children and their parents suffering from mental ill health. Both topics, however, are highly relevant. The findings are presented thematically. Despite the growing body of evidence about associations between spirituality and health outcomes it is to be noted that such associations have to be interpreted in suitable causal networks, taking into account the historical developments and socio-cultural specificities (29). This means that care models or assessment tools that function in one country, do not necessarily serve the same purpose elsewhere.

Results

Various themes concerning spiritual care for patients with neurological diseases and their caregivers have been identified throughout the literature. Eight main topics were identified dealing with challenges regarding spirituality and spiritual care of patients with neurodegenerative diseases, proposing solutions to face these challenges in patients and their caregivers. The themes are as follows: localization of spirituality and religious beliefs in brain, self-perception, personal beliefs, unmet needs and loss of faith, spiritual wellbeing, group support, spiritual legacy work, and dignity therapy.

Localization of spirituality and religious beliefs in the brain

Over the past decade scientists have tried to locate the spirituality and religious beliefs in brain areas. Quite a number of publications exist in which religious beliefs are shown to be connected to certain brain regions. Especially grey matter volume has been found to correlate with spirituality (32). Furthermore, the complex network of subcortical and fronto-parietal areas as well as temporal areas seems to play an important role in spirituality. But also other brain regions are involved in the context of religious feelings like the limbic system, the thalamus, the insular cortex, the anterior and posterior cingulate cortices (33,34). According to these data, it is unsurprising that neurodegenerative disorders and other causes of brain damage can modulate religious and spiritual experiences. Recently, it has been demonstrated that lesions of specific brain areas can modulate spiritual experiences (35). That fronto-temporal dementia or temporal lobe epilepsy changes religious behavior is well known (36,37). Knowing that changes in brain have implication on our beliefs and values, it is important to consider spirituality and (religious) beliefs whilst caring for people with neurological diseases.

Self-perception

The diagnosis of neurodegenerative disease is devastating for patients and their families. It challenges the patients emotionally (38), compromises identity, challenges independence, forces patients and their caregivers into social isolation (39) and threatens the ability to find meaning and purpose in life (40). In addition, the family members feel sad due to the diagnosis, experience fear because of the uncertainty of the future, lack of knowledge and difficulty of accepting the disease. The physical presence but psychological or emotional absence leads to the feeling that the person is absent and the relationship is lost. This may lead to anticipatory grieving, beginning with the diagnosis, through disease related deterioration, and continue after patient’s death (41). Patients’ narratives report on three stages of bodily failure that affect the self-precision. These three stages are: “body failing prematurely and searching for answers”, “body deterioration and responses to care”, and “body nearing its end and needing to talk.” (42). Accordingly, the most difficult challenge for people with neurodegenerative diseases is maintaining a sense of self in the context of a neurological condition (43-47). Patients cannot be left alone with the feeling of losing self (48). Penner et al. suggest “care must attend to the deep needs of these individuals by communicating in a style that addresses both emotional and cognitive needs of patients, by thorough and holistic assessment and by appropriate referrals.” (46).

Personal beliefs

Personal beliefs, unmet needs, and distress affect patients’ and caregivers’ illness experiences alike. Compared to those with chronic liver disease, patients with epilepsy had limited understanding of the illness, and poor belief in personal control and treatment control. They had a negative emotional response to their illness, and were afraid of the effects on the patient or patient's family (49). In Saudi society belief in supernatural factors as a cause for neurological and psychiatric illness, including the evil eye, divine testing and punishment, and sorcery is still very much prevailing (50). In many parts of the world, the patient with epilepsy was (and unfortunately still is) considered to be unclean, touched by evil forces, and contagious, at others, he or she was considered divine magic, and able to utter prophetic oaths (51). Existential dangers and uncertainties worsen patients’ illness experiences, even if good clinical care is available. A Scottish study argues that illness beliefs together with financial situation are stronger predictors of poor outcome than the number of symptoms, disability and distress (52). Lulé et al. measured determinants in ALS patients, the outcomes indicate that whereas the quality of life and depression were not determinants for decisions for life-prolonging treatments nor for the desire to shorten life, the feeling of being a burden was a predictor for decisions against life supporting treatments (53). Patients with emotional coping strategies, avoidant personality types and more dominant beliefs about Parkinson’s disease as part of a person’s identity demonstrated heightened anxiety and depression (54).

Unmet needs and loss of faith

Unmet needs are generally seen as “issues of concern for which the individual perceives they require assistance.” (55). Determining someone’s needs means considering his or her values and preferences, previous and current wishes, and at advanced stages of disease consultation with families and other carers. Studies on patients and caregivers with neurodegenerative disease report on various unmet needs that may lead to the loss of faith and spiritual distress. For example, in people with Parkinson’s disease the highest unmet needs were those of therapeutic, followed by social/spiritual/emotional needs, a need for certainty and physical needs (56). In South Australia caregivers of patients with neurological conditions reported significantly more unmet needs in emotional, spiritual, and bereavement support than caregivers of people with other disorders such as cancer (57). In this context, the common caregiver challenges in this context are fatigue, planning for patient's institutional placement, and anger (58). If the needs are unmet, people lose faith not only in higher transcendent powers but also in the local healthcare system and especially in the neurologists’ responsible diagnosis and care. This may force them to seek treatments in other countries, which again often relates to false promises and broken hopes (59). As an example, the Spiritism philosophy is being spread worldwide as a complementary treatment to neurological disorders, particularly epilepsy and mental health issues (60), and is often executed by faith healers and traditional healers as well as shamans and representatives of different faith groups.

Spiritual wellbeing

The impact of spiritual wellbeing on decision-making is evident. Studies have shown that spirituality is a key component of overall wellbeing and it assumes multidimensional and unique functions. Spiritual wellbeing is a source of happiness (or unhappiness) and subsequent well-being for people (61). Individualised care that promotes engagement in decision-making and considers patients’ spiritual needs is essential for promoting patient empowerment, autonomy and dignity (62). Wade et al. from U.S. demonstrate that patients with a strong existential spiritual belief system enjoyed greater happiness while confronting the lifestyle threat of neurological illness. The relationship between spiritual beliefs and happiness was related to secular, or existential spiritual beliefs, and not the religious conviction. They suggest that focussing on spiritual care for older persons is significant as they are confronted by the loss of a loved one, decline in mental and physical function, and ultimately their own mortality (63). Creating spiritual wellbeing must not be complicated. For example, mealtimes that make patients feel comfortable and homely are part of existential care that leads to positive experience (39).

Group support

Interventions to foster positive living with neurodegenerative disease in clinical practice should integrate strategies to tackle and prevent loneliness and interagency elements to increase community resources and systems of support (64). Support group intervention programmes enhance meaning making of participant’s subjective experiences and help to define purpose in their lives. Furthermore, caregivers cope with the unpredictability of caregiving demands through reflection on personal faith beliefs that value a focus on the present rather than an unknown future (65). Religious involvement, which typically contains a strong element of group support, is evidently associated with better caregiver adaptation in female caregivers (66). The search for religious support is however associated with social determinants, such as education and economical status. In a study conducted in Brazil, epilepsy patients with less formal education presented a significantly higher score for the positive spiritual and religious coping index (SRC), and the unemployed showed higher scores for the negative SRC index (67). Another Brazilian study with Alzheimer disease caregivers reports that spirituality and faith are “facilitators in the development process of the disease, associated with hope and the belief of a higher/divine existence that gives strength and feeds the desire of improvement and cure every day.” (41) A small exploratory study, about the unmet needs of families and PD patient’s being cared for in nursing homes from Austria, indicates that caregivers feel relieved and comforted, when their care dependant relative is placed in nursing home (68). The feeling of not being solely responsible for the patient’s health status, hope that the patient receives good care, and sometimes, is able to participate in activities, such as being able to play cards again, contribute to the feeling of being supported and belonging. Globally, the low number of care facilities combined with high out of pocket payments, long waiting lists, and limited supplies, make it difficult for caregivers to use of such supportive offers.

Spiritual legacy work

Rev Temple-Jones calls for all healthcare providers to consider “creatively rethinking their actions and values” when interacting with patients (48). “Hear My Voice” is a care program designed to provide an opportunity for persons with progressive neurologic illnesses, including brain tumors and other neurodegenerative diseases, to review and discuss their spirituality with a board-certified healthcare chaplain. The aim of this care model is to prepare a spiritual legacy document. The primary results demonstrate the feasibility of this spiritual intervention “helping patients with brain tumors and other progressive neurologic conditions preserve their unique spiritual voices.” (69,70).

Dignity therapy

First established on an empirical model by Chochinov (71), Dignity Therapy is widely accepted in Palliative Care. Aoun et al. [2015] demonstrate that dignity therapy for people with motor neuron disease and their family caregivers “established the importance of narrative and generativity for patients” whereas the “family caregivers overwhelmingly agreed that the dignity therapy document is and will continue to be a source of comfort to them and they would recommend dignity therapy to others in the same situation.” (72) In another cohort, the majority of participants found dignity therapy to be satisfactory, helpful to them and their families, and would recommend dignity therapy to others with similar diseases. Patients with MND reported the strongest positive improvements in the dignity-related areas of looking after unfinished business, continuity of self-acceptance, and role preservation. There were lesser improvements in feeling like a burden, increased will to live, lessened sadness or depression, and sense of control (73). In another study people with ALS, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), end stage renal disease (ESRD) and the frail elderly filled out the Patient Dignity Inventory (PDI). The findings demonstrate that those whose dignity was intact reported fewer PDI items as problematic relative to those whose dignity was fractured. PDI items that most significantly distinguished these groups included worrying about the future, feeling like I am no longer who I used to be, feelings of unfinished business, feeling of being a burden to others, not having control over my life, feeling that my health and care needs have reduced my privacy, and not being able to accept the way things are. Fractured dignity correlated strongly to intensity of suffering, hopelessness, desire for death, and overall decreased life satisfaction and fulfilment (74).

Discussion

The core concepts related to spirituality, such as spiritual pain, spiritual suffering, spiritual wellbeing and spiritual distress have been explored and analysed across the literature. If left without definition, all these concepts can be regarded as effectively meaningless. Spirituality in itself is very subjective and it changes depending on individual’s perception of self, personal aspirations and unmet needs, and other possible life stressors, such as self-perceived loneliness or financial concerns. The subjectivity of all these notions and endless field of possible determinants that may affect patients’ and their caregivers’ are the main reason, why the recent EAPC White Paper on spiritual care education in palliative care differs from earlier papers in this field (28). This encourages the initial conversation about spirituality, which allows the patient to express his or her beliefs and values. Such conversations establish connection between patient, caregiver and the healthcare provider. A conversation about spirituality is to be seen as a crucial first step in establishing a therapeutic relationship, which prepares the ground for screenings and clinical assessments that take place in parallel, but cannot replace the conversation. As spirituality is not necessarily a matter of everyday conversations in clinical setting, such initial conversations prepare patients to share aspects that otherwise might be considered as very private. The patient’s choice to disregard this aspect of care is to be respected (28,75).

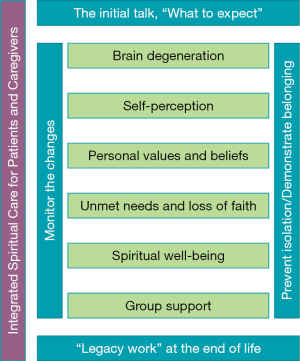

Based on the reviewed literature the integrated spiritual care model for patients with neurodegenerative diseases and their caregivers can be depicted as follows (Figure 1). This figure also serves as an implication for best practice.

Giving the diagnosis and discussing what to expect

Receiving a diagnosis of neurodegenerative disease is devastating for patients and their families in many ways, and therefore, giving such a diagnosis requires preparation, forethought, sensitive and individualised care on the part of the neurologist. Important is to consider where and how the diagnosis is given and what kind of supports from multidisciplinary healthcare team and allied professionals might be required. It is essential to consider the timing, the amount of given information and the quality and purpose of distributed supporting materials. Consideration that understanding the diagnosis might be changed already in the early course of the disease and that the acceptance of the diagnosis might be limited must be also taken into account. As mentioned earlier values and beliefs might have also changed, and thus, it would be good to address these aspects since it might be helpful in coping with the diagnosis. Furthermore, it has been shown that the emotional reactions of the neurologist may cause a lasting impression on those receiving the diagnosis (38). The new science of prognostication—the estimating and communication “what to expect”—is in its infancy and the evidence base to support “best practices” is lacking. Across the world, cultural practices, superstitious beliefs, ignorance, and social stigma may impede the delivery of neurologic care (8). “Honest communication about uncertainties over prognosis and the impact of interventions and ascertainment of individuals’ values and beliefs make for better care.” (76). Hence, formulating a prediction and communicating “what to expect” with patients, families, and surrogates in the context of common neurodegenerative disease is of major importance (77).

When it comes to patients’ and caregivers’ beliefs Adams et al. suggest to:

- Explore illness beliefs openly;

- Enquire longitudinally about predisposing vulnerabilities, acute precipitants and perpetuating factors that may be further elucidated over time;

- Facilitate psychotherapy engagement by actively listening for potentially unhelpful or maladaptive patterns of thoughts, behaviours, fears or psychosocial stressors that can be reflected back to the patient;

- Enquire about the fidelity of individual treatments and educate other providers who may be less familiar with functional neurological disorder (78).

Similar belief and value based care model for people with life-limiting conditions has been proposed by Arthur Kleinman already decades ago (79,80). Kleinman argued that finding a proper explanation for falling ill may be seen as the first step towards coping with the disease (79). What Kleinman calls “explanatory models”, are patients’ and caregivers’ responses to particular situations and are therefore idiosyncratic, changeable and heavily influenced by both personality and cultural factors (27). Therefore, the idea of being incurably ill and dying must be continuously negotiated (80). This continuous negotiation must take place between healthcare providers, patients and caregivers. It has been estimated that the spiritual needs change during the progression of the disease (81). In this regard, not only clinical work, but research in spiritual care for patients with neurological diseases has to be capable of capturing the stages of bodily failure, changes in self, feeling of not belonging or being a burden—this all to prevent distress, suffering and pain as well as loss of faith, particularly in healthcare providers. Snyder et al. point out a global challenge which all health professionals and policy makers should consider, namely, the causes of loss of faith in their domestic care systems and balance the benefits of empowerment and renewed hope against concerns that unproven interventions may create new health risks (59) and increase patients’ out-of-pocket payments.

Monitoring the changes

Up to this day, patient and caregiver driven agendas are understudied in palliative care (82). The subjectivity of spirituality, like other concepts in spiritual care practice and research, force to look for less exploited methods and approaches to address this important health determinant. According to reviewed literature, understanding the complexity of being diagnosed with incurable condition, and how this affects patients’ sense of self is particularly important. As people differ, they adopt varying strategies in critical situations, which may be as follows: (I) avoidance and denial, (II) cognitive reframing, (III) articulation of the self through imagined positive identity, (IV) strategies that reconnect to identity in the past, (V) adjusting and altering goals, (VI) spiritual activities, (VII) humour, (VIII) comparison with others: identity as shaped through social constructs, and (IX) creating communities: a reciprocal reflection of self (43). Regarding supporting the changes in self, narrative and qualitative approaches seem more forthcoming than using the clinical assessment instruments (24,28,83). Even if a large number of such instruments have been developed, these are not meant for multidisciplinary use and are rarely tested in patients with neurological disease. Furthermore, there is little evidence in their effectiveness and critical reviews are seldom.

Legacy work at the end of life

In his significant essay “Life in Quest of Narrative”, Paul Ricoeur has stated that composing a lifestory “is a mediation between man and world (referentiality), between man and man (communicability) and between man and himself (self-understanding).” (84). Biography work, where patients’ biography is told, written down, edited, and exquisitely bound as a keepsake, is gaining ground in palliative care. The literature review revealed several articles featuring the work of board certified healthcare chaplains. The following two approaches were presented: spiritual legacy work and dignity therapy. Best [2019] has thoroughly analysed the literature regarding the concept of dying with dignity. She concludes that the meaning of dignity is solely dependent on the personal beliefs of an individual patient. Therefore, she promotes the idea of biography work when confronted with life-limiting illness: “healthcare workers are in the position to promote dignity in dying by encouraging patients to articulate their preferences and learning to listen to what they say.” (85). Spiritual legacy work and dignity therapy—as biography oriented clinical interventions—matter, because of the mutual endeavour of healthcare providers, patient and caregiver(s). Furthermore, such patient-oriented approach creates a unique situation, where healthcare providers really listen and patients talk, at the same time feeling supported, guided and cared for.

Preventing isolation and demonstrating belonging

Although support groups seem to improve the state of mind of heavily burdened caregivers, it is also known that caregivers are unable to participate in such groups. Online support groups may be a feasible alternative for those who use social media or telepalliative support (86). Another alternative is providing support groups in which caregivers have the chance to meet and talk to each other; at the same time patients with neurodegenerative diseases are being cared for and involved in some activities, such as going for walks, being read aloud to, singing, etc., simultaneously, but in a separate room. An integrated care management led by a specially trained nurse at patient’s home, might help reduce suffering for all involved (87). Further support could be made available via volunteers’ visits to offer opportunities for self-reflection, feeling of being taken care of and belonging.

Conclusions

The aim of this literature based review article was to explore the state and status of spiritual care as an integrated approach to palliative care for patients with neurological diseases and their caregivers. Healthcare professionals can integrate several activities to support patients with neurological diseases and to value their spiritual needs. The spiritual aspect of palliative care should be considered when it comes to self-perception of the patients. There has to be spiritual support and the attempt to meet patients’ needs when it comes to the feeling of losing the self during neurodegenerative condition. Due to the fact that personal beliefs and the understanding of the illness are connected with emotions and experiences, it is necessary to pay attention to it during the course of illness. Meeting someone’s needs means to pay attention to his or her values, preferences, wishes and to integrate relatives in the care process. Individualised care that supports engagement in decision-making and therefore spiritual well-being is essential for promoting patient empowerment, autonomy and dignity. Healthcare professionals should know about interventions like support group programmes that can enhance meaning making of participant’s subjective experiences and help to define purpose in live. Spiritual legacy work is an opportunity for people with progressive neurologic diseases to talk about their spirituality with healthcare chaplains. Dignity therapy is a way to help patients to deal with unfinished business and to enhance self-acceptance and role preservation. Developing belief and value based care models for people with life-limiting neurodegenerative conditions and their caregivers to prevent health related suffering has to be ongoing.

Acknowledgments

Funding: None.

Footnote

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/apm.2020.03.37). The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- World Health Organization. Strengthening of Palliative Care as a Component of Integrated Treatment throughout the Life Course. J Pain Palliat Care Pharmacother 2014;28:130-4. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- IAHPC. Global Consensus based palliative care definition. The International Association for Hospice and Palliative Care, Houston, TX. 2018. Avaialbe online: https://hospicecare.com/what-we-do/projects/consensus-based-definition-of-palliative-care/definition/

- Hawley P. Barriers to Access to Palliative Care. Palliative care 2017;10:1178224216688887. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Boersma I, Miyasaki J, Kutner J, et al. Palliative care and neurology: time for a paradigm shift. Neurology 2014;83:561-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Borasio GD. The role of palliative care in patients with neurological diseases. Nat Rev Neurol 2013;9:292. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Knaul FM, Bhadelia A, Rodriguez NM, et al. The Lancet Commission on Palliative Care and Pain Relief: findings, recommendations, and future directions. Lancet Glob Health 2018;6:S5-6. [Crossref]

- Organization WH. Neurological disorders: public health challenges. 2006.

- Singhal BS, Khadilkar SV. Neurology in the developing world. Handb Clin Neurol 2014;121:1773-82. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Baatiema L, de-Graft Aikins A, Sav A, et al. Barriers to evidence-based acute stroke care in Ghana: a qualitative study on the perspectives of stroke care professionals. BMJ Open 2017;7:e015385. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lorenzl S, Nubling G, Perrar KM, et al. Palliative treatment of chronic neurologic disorders. Handb Clin Neurol 2013;118:133-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Oliver D, Silber E. End of life care in neurological disease. End of life care in neurological disease. Springer; 2013:19-32.

- Oliver DJ, Borasio G, Caraceni A, et al. A consensus review on the development of palliative care for patients with chronic and progressive neurological disease. Eur J Neurol 2016;23:30-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Robinson MT, Holloway RG. Palliative Care in Neurology. Mayo Clin Proc 2017;92:1592-601. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Titova N, Chaudhuri KR. Palliative Care and Nonmotor Symptoms in Parkinson's Disease and Parkinsonism. Int Rev Neurobiol 2017;134:1239-55. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Veronese S, Gallo G, Valle A, et al. Specialist palliative care improves the quality of life in advanced neurodegenerative disorders: NE-PAL, a pilot randomised controlled study. BMJ Support Palliat Care 2017;7:164-72. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Connolly S, Galvin M, Hardiman O. End-of-life management in patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Lancet Neurol 2015;14:435-42. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Miyasaki JM, Long J, Mancini D, et al. Palliative care for advanced Parkinson disease: an interdisciplinary clinic and new scale, the ESAS-PD. Parkinsonism Relat Disord 2012;18 Suppl 3:S6-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Yeager S, Doust C, Epting S, et al. Embrace hope: an end-of-life intervention to support neurological critical care patients and their families. Crit Care Nurse 2010;30:47-58. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Centeno C, Arias-Casais N. Global palliative care: from need to action. Lancet Glob Health 2019;7:e815-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- The Lancet Neurology. Integrating palliative care into neurological practice. Lancet Neurol 2017;16:489. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gofton TE, Chum M, Schulz V, et al. Challenges facing palliative neurology practice: A qualitative analysis. J Neurol Sci 2018;385:225-31. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- WHO. Handbook of Resolutions and Decisions, Vol. II, p.5-6 2. The determinants of health. In: WHA, editor. Geneva: World Health Organization; 1985.

- Organization WH. The Spiritual Dimension. 1991.

- Paal P, Lorenzl S. Patients with Parkinson’s disease need spiritual care. Ann Palliat Med 2019. [Epub ahead of print]. [PubMed]

- Nolan S SP, Leget CJW. Spiritual care in palliative care: working towards an EAPC Task Force. Eur J Pall Care 2011;18:86-89.

- Koper I, Pasman HRW, Schweitzer BPM, et al. Spiritual care at the end of life in the primary care setting: experiences from spiritual caregivers - a mixed methods study. BMC Palliat Care 2019;18:98. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Taylor C. Secular Age. Cambridge, Massachussets: Harvard University Press; 2007.

- Best M, Leget C, Goodhead A, et al. An EAPC white paper on multi-disciplinary education for spiritual care in palliative care. BMC Palliat Care 2020;19:9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Frick E. Spiritual Care – How does it work? Spiritual Care 2017;6:223-4. [Crossref]

- Gijsberts MHE, Liefbroer AI, Otten R, et al. Spiritual Care in Palliative Care: A Systematic Review of the Recent European Literature. Med Sci (Basel) 2019. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Best M, Butow P, Olver I. Doctors discussing religion and spirituality: A systematic literature review. Palliat Med 2016;30:327-37. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Tang YY, Hölzel BK, Posner MI. The neuroscience of mindfulness meditation. Nat Rev Neurosci 2015;16:213-25. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Fingelkurts AA, Fingelkurts AA. Is our brain hardwired to produce God, or is our brain hardwired to perceive God? A systematic review on the role of the brain in mediating religious experience. Cogn Process 2009;10:293-326. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- van Elk M, Aleman A. Brain mechanisms in religion and spirituality: An integrative predictive processing framework. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 2017;73:359-78. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Urgesi C, Aglioti SM, Skrap M, et al. The Spiritual Brain: Selective Cortical Lesions Modulate Human Self-Transcendence. Neuron 2010;65:309-19. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Arzy S, Schurr R. “God has sent me to you”: Right temporal epilepsy, left prefrontal psychosis. Epilepsy Behav 2016;60:7-10. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Devinsky O, Lai G. Spirituality and Religion in Epilepsy. Epilepsy Behav 2008;12:636-43. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Aoun SM, O'Brien MR, Breen LJ, et al. 'The shock of diagnosis': Qualitative accounts from people with Motor Neurone Disease reflecting the need for more person-centred care. J Neurol Sci 2018;387:80-4. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Beck M, Poulsen I, Martinsen B, et al. Longing for homeliness: exploring mealtime experiences of patients suffering from a neurological disease. Scand J Caring Sci 2018;32:317-25. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Cheston R, Christopher G, Ismail S. Dementia as an existential threat: the importance of self-esteem, social connectedness and meaning in life. Sci Prog 2015;98:416-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Vizzachi BA, Daspett C. Family dynamics in face of Alzheimer's in one of its members. Revista da Escola de Enfermagem da USP 2015;49:931-6. [Crossref]

- Harris DA, Jack K, Wibberley C. The meaning of living with uncertainty for people with motor neurone disease. J Clin Nurs 2018;27:2062-71. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Roger K, Wetzel M, Hutchinson S, et al. "How can I still be me?": Strategies to maintain a sense of self in the context of a neurological condition. Int J Qual Stud Health Well-being 2014;9:23534. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hermanns M. The invisible and visible stigmatization of Parkinson's disease. J Am Assoc Nurse Pract 2013;25:563-6. [PubMed]

- Murdock C, Cousins W, Kernohan WG. "Running Water Won't Freeze": How people with advanced Parkinson's disease experience occupation. Palliat Support Care 2015;13:1363-72. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Penner LA, Roger K. The person in the room: how relating holistically contributes to an effective patient-care provider alliance. Commun Med 2012;9:49-58. [PubMed]

- Reynolds D. Spirituality As a Coping Mechanism for Individuals with Parkinson's Disease. J Christ Nurs 2017;34:190-4. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Rev Temple-Jones J. "I want to find my life again": dementia and grief. J Pastoral Care Counsel 2012;66:1-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ji H, Zhang L, Li L, et al. Illness perception in Chinese adults with epilepsy. Epilepsy Res 2016;128:94-101. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Tayeb H, Khayat A, Milyani H, et al. Supernatural Explanations of Neurological and Psychiatric Disorders Among Health Care Professionals at an Academic Tertiary Care Hospital in Saudi Arabia. J Nerv Ment Dis 2018;206:589-92. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Trimble M. The Contribution of Neurological Disorders to an Understanding of Religious Experiences. Handbook of Neuroethics 2015:1535-52.

- Sharpe M, Stone J, Hibberd C, et al. Neurology out-patients with symptoms unexplained by disease: illness beliefs and financial benefits predict 1-year outcome. Psychological Medicine 2010;40:689-98. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lulé D, Nonnenmacher S, Sorg S, et al. Live and let die: existential decision processes in a fatal disease. J Neurol 2014;261:518-25. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Garlovsky JK, Overton PG, Simpson J. Psychological Predictors of Anxiety and Depression in Parkinson's Disease: A Systematic Review. J Clin Psychol 2016;72:979-98. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lipscomb J, Gotay C, Snyder C. editors. Outcomes Assessment in Cancer: Measures, Methods and Applications. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2004.

- Lee J, Kim Y, Kim S, et al. Unmet needs of people with Parkinson’s disease: A cross-sectional study. J Adv Nurs 2019;75:3504-14. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Aoun S, McConigley R, Abernethy A, et al. Caregivers of people with neurodegenerative diseases: profile and unmet needs from a population-based survey in South Australia. J Palliat Med 2010;13:653-61. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Stewart TV, Loskutova N, Galliher JM, et al. Practice patterns, beliefs, and perceived barriers to care regarding dementia: a report from the American Academy of Family Physicians (AAFP) national research network. J Am Board Fam Med 2014;27:275-83. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Snyder J, Adams K, Crooks VA, et al. "I knew what was going to happen if I did nothing and so I was going to do something": faith, hope, and trust in the decisions of Canadians with multiple sclerosis to seek unproven interventions abroad. BMC Health Serv Res 2014;14:445. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Vancini RL, Lira CA, Vancini-Campanharo CR, et al. The Spiritism as therapy in the health care in the epilepsy. Revista Brasileira de Enfermagem 2016;69:804-10. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Chirico F. Spiritual well-being in the 21st century: It is time to review the current WHO’s health definition. J Health Soc Sci 2016;1:11-6.

- Rego F, Gonçalves F, Moutinho S, et al. The influence of spirituality on decision-making in palliative care outpatients: a cross-sectional study. BMC Palliat Care 2020;19:22. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wade J, Hayes R, Bekenstein J, et al. Associations between Religiosity, Spirituality, and Happiness among Adults Living with Neurological Illness. Geriatrics 2018;3:35. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ambrosio L, Portillo MC, Rodriguez-Blazquez C, et al. Influencing factors when living with Parkinson's disease: A cross-sectional study. J Clin Nurs 2019;28:3168-76. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Damianakis T, Wilson K, Marziali E. Family caregiver support groups: spiritual reflections' impact on stress management. Aging Ment Health 2018;22:70-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Koenig HG, Nelson B, Shaw SF, et al. Religious Involvement and Adaptation in Female Family Caregivers. J Am Geriatr Soc 2016;64:578-83. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Tedrus GMAS, Fonseca LC, Magri FDP, et al. Spiritual/religious coping in patients with epilepsy: relationship with sociodemographic and clinical aspects and quality of life. Epilepsy Behav 2013;28:386-90. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lex KM, Larkin P, Osterbrink J, et al. A Pilgrim's Journey-When Parkinson's Disease Comes to an End in Nursing Homes. Front Neurol 2018;9:1068. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Piderman KM, Breitkopf CR, Jenkins SM, et al. The feasibility and educational value of Hear My Voice, a chaplain-led spiritual life review process for patients with brain cancers and progressive neurologic conditions. J Cancer Educ 2015;30:209-12. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Piderman KM, Radecki Breitkopf C, Jenkins SM, et al. The impact of a spiritual legacy intervention in patients with brain cancers and other neurologic illnesses and their support persons. Psychooncology 2017;26:346-53. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Chochinov HM, Hack T, Hassard T, et al. Dignity therapy: a novel psychotherapeutic intervention for patients near the end of life. J Clin Oncol 2005;23:5520-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Aoun SM, Chochinov HM, Kristjanson LJ. Dignity therapy for people with motor neuron disease and their family caregivers: a feasibility study. J Palliat Med 2015;18:31-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bentley B, O'Connor M, Kane R, et al. Feasibility, acceptability, and potential effectiveness of dignity therapy for people with motor neurone disease. PLoS One 2014;9:e96888. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Chochinov HM, Johnston W, McClement SE, et al. Dignity and Distress towards the End of Life across Four Non-Cancer Populations. PLoS One 2016;11:e0147607. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Paal P, Frick E, Roser T, et al. Expert Discussion on Taking a Spiritual History. J Palliat Care 2017;32:19-25. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Harwood RH. Feeding decisions in advanced dementia. J R Coll Physicians Edinb 2014;44:232-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Holloway RG, Gramling R, Kelly AG. Estimating and communicating prognosis in advanced neurologic disease. Neurology 2013;80:764-72. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Adams C, Anderson J, Madva EN, et al. You've made the diagnosis of functional neurological disorder: now what? Pract Neurol 2018;18:323-30. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kleinman A. Patients and Healers in the Context of Culture. An Exploration of the Borderland between Anthropology, Medicine, and Psychiatry. Berkeley, Los Angeles & London: University of California Press; 1980.

- Kleinman A. The Illness Narrative. Suffering, Healing & the Human Condition. New York: Basic Books; 1988.

- Lunder U, Furlan M, Simonic A. Spiritual needs assessments and measurements. Curr Opin Support Palliat Care 2011;5:273-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hasson F, Nicholson E, Muldrew D, et al. International palliative care research priorities: A systematic review. BMC Palliat Care 2020;19:16. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Monod S, Brennan M, Rochat E, et al. Instruments Measuring Spirituality in Clinical Research: A Systematic Review. J Gen Intern Med 2011;26:1345. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ricoeur P. Life in Quest of Narrative. On Paul Ricoeur: Narrative and interpretation. London & New York: Routledge; 1991.

- Best M. Dignity in Palliative Care. In: MacLeod RD, Van den Block L. editors. Textbook of Palliative Care. Springer Nature Switzerland AG, 2019:1-11.

- Shah SP, Glenn GL, Hummel EM, et al. Caregiver tele-support group for Parkinson's disease: A pilot study. Geriatr Nurs 2015;36:207-11. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Eggers C, Dano R, Schill J, et al. Access to End-of Life Parkinson's Disease Patients Through Patient-Centered Integrated Healthcare. Front Neurol 2018;9:627. [Crossref] [PubMed]