Quality of life and its associated factors for mild chronic obstructive pulmonary disease patients of urban community settings

Introduction

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is a serious public problem worldwide. In 2010, the prevalence of COPD was 11.7% with total number of living patients as 384 million and average death number as about 3 million each year globally (1,2). With increasing rate of smoking in developing countries and aging in developed ones, the number of death due to COPD and its related diseases was estimated to be 4.5 million in 2030 (3,4). In 2008, the prevalence of COPD was 8.2% among adults aged over 40 years from a national epidemiological survey in China, and it was estimated that there was nearly 70% increase in the number of Chinese COPD patients from 30.90 million in 1990 to 51.52 million in 2010 (5,6). Airway obstruction is the most important clinical symptom of COPD and frequently impairs the quality of life (QoL) through limiting exercise capacity, sapping social function and inducing mental problems such as anxiety and depression (7-12). In a Korean cohort study, 59.2% of the mild-to-moderate COPD patients and 80.4% of the severe-to-very severe patients suffered from worse QoL (13). Some previous findings suggested that several factors including age, gender, socioeconomic status, body mass index (BMI), exacerbation, severity, exercise capacity and comorbidities were statistically related to the QoL in COPD patients (14-18). In one previous study, there was worse QoL among middle-aged than older-adult participants, which could be attributed to greater dyspnea severity (19). In another previous study including moderate to severe COPD patients, women had worse scores due to dyspnea and oxygenation in QoL (20). Some studies found that as lower socioeconomic status, lower household income was associated with worse QoL (21-23). It was observed that obese cases with COPD had worse QoL than those with the normal-weight (24). Some surveys indicated that COPD exacerbation adversely influenced QoL through increased levels of fatigue, decreased sleep time and sleep efficiency (25-31). A recent research reported that decreasing physical activity was significantly associated with the impairment of QoL among COPD patients at moderate and more severe stage, which could be partly because of their more dyspnea, more comorbidities and declining in lung function (32). In addition, comorbidities, such as chronic bronchitis, musculoskeletal symptoms and depression, were associated with worse QoL among severe and very severe COPD patients (33). However, few focused on the QoL and its influencing factors among mild COPD patients in Chinese community settings (32,34-40). This study was aimed to evaluate the QoL of mild COPD patients and their influencing factors in Shanghai.

Methods

Study site and population

During June to August in 2016, a cross-sectional study was carried out in Pudong New Area of Shanghai, China, and 300 cases with mild COPD were recruited into this study from six, randomly selected from 46 communities. At the enrollment, all subjects received spirometry function test to verify their COPD severity. The inclusion and exclusion criteria of subjects were detailed previously (41,42). Finally, 275 (91.7%) of 300 patients met all the criteria and were included in this analysis.

Data collection and quality control

All information was collected by using a structured questionnaire and a physical examination. Demographic information included age, gender, alcohol drinking history (Yes/No), smoking history (Yes/No), years of education (<9 years/≥9 years), monthly household income (<3,000 RMB/≥3,000 RMB), and BMI (kg/m2) (BMI≤18.5: underweight; 18.5< BMI ≤23.9: normal; BMI ≥24.0: overweight/obesity). Clinical information collected included six-minute walking test, regular use of COPD medications in the past 12 months (Yes/No), and chronic comorbid conditions (hypertension, diabetes, kidney disease, stroke, cardiovascular diseases and/or others). Specific training and double check for all data were used to improve the research quality. Details have been presented elsewhere (42).

Measurements of QoL

EuroQoL five-dimension questionnaire (EQ-5D) was developed by the EuroQoL Group to evaluate QoL from multiple dimensions (43-45), and this scale comprises descriptive system of health status and a visual analog scale (EQ-VAS). The descriptive system of health status contains five dimensions (mobility, self-care, usual activities, pain/discomfort, and anxiety/depression) and each dimension has three levels (no problem, moderate problem, and severe problem). Utility index score was calculated with Chinese time trade-off values for EQ-5D health states, and the score ranges from –0.149 to 0.887 (46). EQ-VAS was used to assess health status by participants themselves, and the score of scale indicates health states from the worst [0] to the best [100]. EQ-5D-China, as a self-administered scale, has been widely applied into assessing the QoL among Chinese population (47-50).

Spirometry function test and physical examination

Spirometry function test was performed according to a standard procedure (42). The 6-minute walking test was performed with a long straight corridor with 30 m in length on a flat and hard ground, and every three meters of corridor was marked with a horizontal line. Patients were required to walk as far as possible in six minutes after standardized instructions, and received appropriate encouragement during the test (38-40).

Statistical analysis

Data analysis was performed by using SAS 9.2 for Windows (SAS Institute, Inc, Cary, NC). Categorical variables were compared with Pearson Chi square test or Fisher exact test. Continuous variables with and without normal distribution were tested by using Student t-test and Wilcoxon test for two group comparisons. Utility of QoL, as dependent variable, was grouped into the top quarter (top 25%) with a score of ≥0.847 and the low three quarter (low 75%) with a score of <0.847. Logistic regression analysis was used to estimate crude odds ratio (cOR), adjusted OR (aOR) and their 95% CI for factors associated with utility of QoL. The P value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Written informed consent was obtained from all participants. They were permitted to withdraw from the study at any time without negative consequences. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (as revised in 2013). Ethical approval for this study was issued by the Institutional Review Board of the Fudan University School of Public Health (No.2016-07-0597).

Results

Basic characteristics of subjects

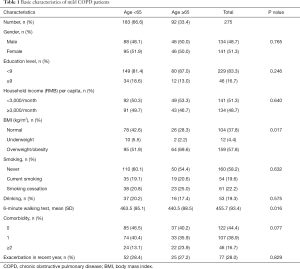

Among 275 subjects, the average age was 61.5±6.0 years old and nearly half (48.7%) were male. Most (83.3%) of them received education less than 9 years, and about half (48.7%) earned monthly household income per capita of 3,000 RMB or more. Nearly two fifth and one fifth of them had a history of smoking and alcohol drinking, respectively. The participants had average BMI of 25.1±4.0 (kg/m2), and younger patients (<65 years) had a higher proportion of normal weight than the older (42.6% vs. 28.3%/37.8, P=0.017), and the former finished longer length of distance during 6-minute walking test than older patients. More than half had comorbidity and approximately 30% experienced exacerbation in the past year, respectively (Table 1).

Full table

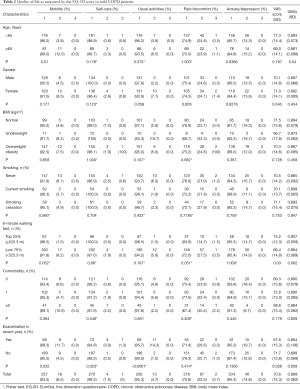

Evaluation of QoL

The overall VAS scores and utility of QoL were 70.6±14.3 and 0.889±0.082, respectively. “No problem” was the most frequent response for all five dimensions, including mobility (93.5%), self-care (98.5%), pain/discomfort (95.3%), usual activities (78.5%), and anxiety/depression (85.4%). Table 2 shows that subjects who were elder (≥65 years) or female were more likely to have a moderate problem in mobility. Subjects with poor exercise capacity (shorter distance of 6MWT <525.3 m) had a lower VAS score than those with relatively better exercise performance. In addition, subjects with any exacerbation in the last year had significantly higher proportions of moderate problem in mobility, self-care, and usual activities, lower VAS score and poorer utility of QoL.

Full table

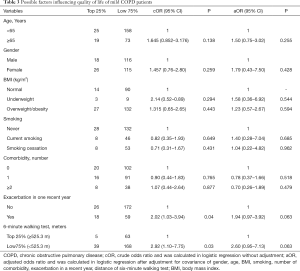

Factors associated with QoL

Single-factor logistic regression model showed that both exacerbation in the past year and poorer exercise capacity (distance of 6MWT <525.3 m) were negatively associated with utility of QoL (aORexacerbation =2.02, 95% CI: 1.03-3.94; aORdistance =2.92, 95% CI: 1.10–7.75). In multi-factor logistic regression, the associations were slightly weakened (Table 3).

Full table

Discussion

In this cross-sectional study, the overall VAS score and utility of QoL were 70.6 and 0.889 among mild COPD patients on average, which was similar to that of mild COPD patients in another Chinese study (VAS =70.0, utility =0.848) (50). The VAS score in this study was lower than that among general populations of China (80.1), South Korea (79.4), Poland (79.3), and the USA (79.2) (51-54). The utility of QoL was also lower than that from China (0.951), but similar to that from Poland (0.897) and the USA (0.866) among general populations (51,53,54). The utility of QoL among Chinese population with or without hypertension (0.9212–0.9787) was higher than that of this study (46). There are two major reasons for the observed differences: (I) different time trade-off values for EQ-5D health states caused by innate variance among the studies (55-57); and (II) different age distribution for the study populations. The population in our study was aged over 40 years, while the US study 41% of people aged less than 40 years.

Our study indicated that exacerbation in the past year was negatively associated with QoL, which was similar to the results from other studies (58-60). Aaron et al. found that after 24 months, exacerbation was still significantly correlated with aggravation in symptoms (61), and caused progressive deterioration of QoL for COPD patients (27). In addition, frequent exacerbation was correlated with worse declining of health status (62). However, majority of patients attained apparent improvements in QoL and breathless after short-term treatment for exacerbation (27). Our study also suggested that poorer exercise capacity (distance of 6MWT <525.3 m) acted in similar way, which was also observed in another study (63). 6MWT can reflect the level of daily activities, and measure functional status of patients (40,64). Improvement on distance of 6-minute walking after medical treatment was associated with the alleviation of dyspnea symptom (65). Besides, the distance of 6MWT decreased with increasing number of comorbidities of COPD patients, which in return undermined the QoL (66).

There are strengths and limitations in this study. This study was conducted in urban communities and all invited subjects participated in the study. All subjects included in the study were confirmed to be at the mild stage of COPD based on a free pulmonary function test after the inhaled specific bronchodilators (salbutamol, 200 mL). However, a cross-sectional study design provided no evidence for causal associations between risk factors and impaired QoL, which needs to be confirmed in future studies. Moderate and severe COPD cases were not involved, and the study also excluded inpatients who likely had worse QoL. Moreover, there were also other factors, such as depression and medicine, were associated with impaired QoL in COPD patients, which called to be determined in further research (33,67).

Conclusions

In conclusion, the QoL was impaired in mild COPD patients living in urban communities and health care services should be provided to these patients. Exacerbation in the past year and exercise capacity were significantly correlated to QoL. More community-based interventions to prevent exacerbation and engage physical activities should be developed to improve QoL at the early stage of COPD.

Acknowledgments

Funding: This work was supported by the Delong Foundation of Fudan School of Public Health (DL2015024) and the National Key Research and Development Program of China (No. 2018YFC1313600). The sponsors have no role in the study design, survey process, data analysis, and manuscript preparation.

Footnote

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/apm-19-655). The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (as revised in 2013). Ethical approval for this study was issued by the Institutional Review Board of the Fudan University School of Public Health (No.2016-07-0597). Written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- Adeloye D, Chua S, Lee C, et al. Global and regional estimates of COPD prevalence: Systematic review and meta-analysis. J Glob Health 2015;5:020415. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- GBD 2013 Mortality and Causes of Death Collaborators. Global, regional, and national age-sex specific all-cause and cause-specific mortality for 240 causes of death, 1990-2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. Lancet 2015;385:117-71. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lopez AD, Shibuya K, Rao C, et al. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: current burden and future projections. Eur Respir J 2006;27:397-412. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- WHO. Projection of mortality and causes of death, 2015 and 2030.

- Chan KY, Li X, Chen W, et al. Prevalence of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) in China in 1990 and 2010. J Glob Health 2017;7:020704. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Zhong N, Wang C, Yao W, et al. Prevalence of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in China: a large, population-based survey. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2007;176:753-60. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Redelmeier DA, Goldstein RS, Min ST, et al. Spirometry and dyspnea in patients with COPD. When small differences mean little. Chest 1996;109:1163-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Belfer MH, Reardon JZ. Improving exercise tolerance and quality of life in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. J Am Osteopath Assoc 2009;109:268-78. [PubMed]

- Sprangers MA, de Regt EB, Andries F, et al. Which chronic conditions are associated with better or poorer quality of life? J Clin Epidemiol 2000;53:895-907. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- van Manen JG, Bindels PJ, Dekker FW, et al. The influence of COPD on health-related quality of life independent of the influence of comorbidity. J Clin Epidemiol 2003;56:1177-84. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Pauwels RA, Rabe KF. Burden and clinical features of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). Lancet 2004;364:613-20. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Andenaes R, Kalfoss MH, Wahl A. Psychological distress and quality of life in hospitalized patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. J Adv Nurs 2004;46:523-30. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lee H, Jhun BW, Cho J, et al. Different impacts of respiratory symptoms and comorbidities on COPD-specific health-related quality of life by COPD severity. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis 2017;12:3301-10. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Fan VS, Curtis JR, Tu SP, et al. Using quality of life to predict hospitalization and mortality in patients with obstructive lung diseases. Chest 2002;122:429-36. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Pereira ED, Pinto R, Alcantara M, et al. Influence of respiratory function parameters on the quality of life of COPD patients. J Bras Pneumol 2009;35:730-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Carrasco Garrido P, de Miguel Diez J, Rejas Gutierrez J, et al. Negative impact of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease on the health-related quality of life of patients. Results of the EPIDEPOC study. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2006;4:31. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Burgel PR, Escamilla R, Perez T, et al. Impact of comorbidities on COPD-specific health-related quality of life. Respir Med 2013;107:233-41. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Weldam SW, Lammers JW, Decates RL, et al. Daily activities and health-related quality of life in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: psychological determinants: a cross-sectional study. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2013;11:190. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Martinez CH, Diaz AA, Parulekar AD, et al. Age-Related Differences in Health-Related Quality of Life in COPD: An Analysis of the COPDGene and SPIROMICS Cohorts. Chest 2016;149:927-35. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- de Torres JP, Casanova C, Hernandez C, et al. Gender associated differences in determinants of quality of life in patients with COPD: a case series study. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2006;4:72. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hong JY, Kim SY, Chung KS, et al. Factors associated with the quality of life of Korean COPD patients as measured by the EQ-5D. Qual Life Res 2015;24:2549-58. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Miravitlles M, Naberan K, Cantoni J, et al. Socioeconomic status and health-related quality of life of patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Respiration 2011;82:402-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Johannessen A, Eagan TM, Omenaas ER, et al. Socioeconomic risk factors for lung function decline in a general population. Eur Respir J 2010;36:480-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Cecere LM, Littman AJ, Slatore CG, et al. Obesity and COPD: associated symptoms, health-related quality of life, and medication use. Copd 2011;8:275-84. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hurst JR, Skolnik N, Hansen GJ, et al. Understanding the impact of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease exacerbations on patient health and quality of life. Eur J Intern Med 2020;73:1-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Martin AL, Marvel J, Fahrbach K, et al. The association of lung function and St. George's respiratory questionnaire with exacerbations in COPD: a systematic literature review and regression analysis. Respir Res 2016;17:40. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Seemungal TA, Donaldson GC, Paul EA, et al. Effect of exacerbation on quality of life in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1998;157:1418-22. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Solem CT, Sun SX, Sudharshan L, et al. Exacerbation-related impairment of quality of life and work productivity in severe and very severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis 2013;8:641-52. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Sato M, Chubachi S, Sasaki M, et al. Impact of mild exacerbation on COPD symptoms in a Japanese cohort. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis 2016;11:1269-78. [PubMed]

- Vanaparthy R, Mota P, Khan R, et al. A longitudinal assessment of sleep variables during exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Chron Respir Dis 2015;12:299-304. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Baghai-Ravary R, Quint JK, Goldring JJ, et al. Determinants and impact of fatigue in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Respir Med 2009;103:216-23. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Esteban C, Quintana JM, Aburto M, et al. Impact of changes in physical activity on health-related quality of life among patients with COPD. Eur Respir J 2010;36:292-300. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Sundh J, Johansson G, Larsson K, et al. Comorbidity and health-related quality of life in patients with severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease attending Swedish secondary care units. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis 2015;10:173-83. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bentsen SB, Miaskowski C, Rustoen T. Demographic and clinical characteristics associated with quality of life in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Qual Life Res 2014;23:991-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Xiang YT, Wong TS, Tsoh J, et al. Quality of life in older patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) in Hong Kong: a case-control study. Perspect Psychiatr Care 2015;51:121-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Black-Shinn JL, Kinney GL, Wise AL, et al. Cardiovascular disease is associated with COPD severity and reduced functional status and quality of life. Copd 2014;11:546-51. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Menn P, Weber N, Holle R. Health-related quality of life in patients with severe COPD hospitalized for exacerbations - comparing EQ-5D, SF-12 and SGRQ. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2010;8:39. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Balke B. A Simple Field Test for the Assessment of Physical Fitness. Rep 63-6. Rep Civ Aeromed Res Inst US 1963:1-8.

- Holland AE, Spruit MA, Troosters T, et al. An official European Respiratory Society/American Thoracic Society technical standard: field walking tests in chronic respiratory disease. Eur Respir J 2014;44:1428-46. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Laboratories ATSCoPSfCPF. ATS statement: guidelines for the six-minute walk test. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2002;166:111-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Vogelmeier CF, Criner GJ, Martinez FJ, et al. Global Strategy for the Diagnosis, Management, and Prevention of Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease 2017 Report: GOLD Executive Summary Informe 2017 de la Iniciativa Global para el Diagnostico, Tratamiento y Prevencion de la Enfermedad Pulmonar Obstructiva Cronica: Resumen Ejecutivo de GOLD. Arch Bronconeumol 2017;53:128-49. [PubMed]

- Xiao T, Qiu H, Chen Y, et al. Prevalence of anxiety and depression symptoms and their associated factors in mild COPD patients from community settings, Shanghai, China: a cross-sectional study. BMC Psychiatry 2018;18:89. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Rabin R, de Charro F. EQ-5D: a measure of health status from the EuroQol Group. Ann Med 2001;33:337-43. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Brooks R. EuroQol: the current state of play. Health Policy 1996;37:53-72. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- EuroQol Group. EuroQol--a new facility for the measurement of health-related quality of life. Health Policy 1990;16:199-208. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Liu GG, Wu H, Li M, et al. Chinese time trade-off values for EQ-5D health states. Value Health 2014;17:597-604. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wang H, Kindig DA, Mullahy J. Variation in Chinese population health related quality of life: results from a EuroQol study in Beijing, China. Qual Life Res 2005;14:119-32. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Luo N, Chew LH, Fong KY, et al. Validity and reliability of the EQ-5D self-report questionnaire in Chinese-speaking patients with rheumatic diseases in Singapore. Ann Acad Med Singapore 2003;32:685-90. [PubMed]

- Chang TJ, Tarn YH, Hsieh CL, et al. Taiwanese version of the EQ-5D: validation in a representative sample of the Taiwanese population. J Formos Med Assoc 2007;106:1023-31. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wu M, Zhao Q, Chen Y, et al. Quality of life and its association with direct medical costs for COPD in urban China. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2015;13:57. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Sun S, Chen J, Johannesson M, et al. Population health status in China: EQ-5D results, by age, sex and socio-economic status, from the National Health Services Survey 2008. Qual Life Res 2011;20:309-20. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kim SH, Jo MW, Ock M, et al. Exploratory Study of Dimensions of Health-related Quality of Life in the General Population of South Korea. J Prev Med Public Health 2017;50:361-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Golicki D, Dudzinska M, Zwolak A, et al. Quality of life in patients with type 2 diabetes in Poland - comparison with the general population using the EQ-5D questionnaire. Adv Clin Exp Med 2015;24:139-46. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lubetkin EI, Jia H, Franks P, et al. Relationship among sociodemographic factors, clinical conditions, and health-related quality of life: examining the EQ-5D in the U.S. general population. Qual Life Res 2005;14:2187-96. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Golicki D, Jakubczyk M, Niewada M, et al. Valuation of EQ-5D health states in Poland: first TTO-based social value set in Central and Eastern Europe. Value Health 2010;13:289-97. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Shaw JW, Johnson JA, Coons SJ. US valuation of the EQ-5D health states: development and testing of the D1 valuation model. Med Care 2005;43:203-20. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Yoo JY, Kim YS, Kim SS, et al. Factors affecting the trajectory of health-related quality of life in COPD patients. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 2016;20:738-46. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Xu W, Collet JP, Shapiro S, et al. Negative impacts of unreported COPD exacerbations on health-related quality of life at 1 year. Eur Respir J 2010;35:1022-30. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Andenaes R, Moum T, Kalfoss MH, et al. Changes in health status, psychological distress, and quality of life in COPD patients after hospitalization. Qual Life Res 2006;15:249-57. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wang Q, Bourbeau J. Outcomes and health-related quality of life following hospitalization for an acute exacerbation of COPD. Respirology 2005;10:334-40. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Aaron SD, Vandemheen KL, Clinch JJ, et al. Measurement of short-term changes in dyspnea and disease-specific quality of life following an acute COPD exacerbation. Chest 2002;121:688-96. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Nonato NL, Diaz O, Nascimento OA, et al. Behavior of Quality of Life (SGRQ) in COPD Patients According to BODE Scores. Arch Bronconeumol 2015;51:315-21. [PubMed]

- Solway S, Brooks D, Lacasse Y, et al. A qualitative systematic overview of the measurement properties of functional walk tests used in the cardiorespiratory domain. Chest 2001;119:256-70. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Niederman MS, Clemente PH, Fein AM, et al. Benefits of a multidisciplinary pulmonary rehabilitation program. Improvements are independent of lung function. Chest 1991;99:798-804. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Da Silva GP, Morano MT, Cavalcante AG, et al. Exercise capacity impairment in COPD patients with comorbidities. Rev Port Pneumol (2006) 2015;21:233-8. [PubMed]

- Huber MB, Wacker ME, Vogelmeier CF, et al. Comorbid Influences on Generic Health-Related Quality of Life in COPD: A Systematic Review. PLoS One 2015;10:e0132670. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Banfi P, Cappuccio A, Latella ME, et al. Narrative medicine to improve the management and quality of life of patients with COPD: the first experience applying parallel chart in Italy. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis 2018;13:287-97. [Crossref] [PubMed]