Clinical outcome of standardized oxygen therapy nursing strategy in COVID-19

Introduction

The novel coronavirus pneumonia (COVID-19), which appeared in late December 2019, has soon become a global pandemic owing to its strong contagiousness. As of April 1, 2020, 823,626 cases were confirmed globally, including 40,598 deaths, in more than 200 countries and regions (1).

The disease progresses rapidly, sometimes leading to severe or critical conditions at an early stage. There are 26.1% to 32.0% of the patients may require ICU admission (2,3). Variable conditions, including acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), septic shock, and even death, are commonly met in these cases (4). Recently, a retrospective study has shown that the 28-day mortality rate of critical COVID-19 patients in ICU is as high as 61.5% (5). ARDS, a severe acute hypoxic respiratory failure and exudative alveolar edema caused by increased pulmonary capillary permeability and alveolar epithelial cell injury, occur after 10.5 days on average (2). According to the Berlin ARDS definition, ARDS is categorized into mild, moderate, and severe degrees (6). A compositive rate of 14% was reported, including dyspnea, tachypnea with a respiratory rate greater than 30 breaths/min, oxygen saturation (SpO2) ≤93%, and reduced oxygenation index (partial pressure of arterial oxygen (PaO2)/fraction of inspired oxygen (FiO2) ratio <300 mmHg) or pulmonary infiltration >50% within 48 hours (7).

The main symptoms of COVID-19 were fever with or without respiratory and other systemic symptoms (2). The most common and severe complication of COVID-19 is acute hypoxemic respiratory failure or ARDS, which requires oxygen and ventilation therapy (5), including a nasal catheter, oxygen inhalation, masked oxygen inhalation, high flow oxygen therapy (HFNO), noninvasive mechanical ventilation (NIV) or invasive mechanical ventilation (8). Experts have proposed that oxygen therapy and mechanical ventilation are the most basic and essential methods of respiratory support for patients with COVID-19 (4,9). However, a technical standard for oxygen therapy nursing, as well as how this would improve clinical outcomes and symptoms in patients COVID-19, is yet to be explored. There is still room for improvement, especially in nursing. Under these circumstances, this study was selected. The purpose of this study was to explore the clinical outcomes of COVID-19 patients treated with standardized oxygen therapy in a single center.

We present the following article in accordance with the STROBE reporting checklist (available at http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/apm-20-1272).

Methods

Study population

All the patients of confirmed COVID-19 were admitted to the 20th ward of the Eastern Branch, Renmin Hospital of Wuhan University from February 9, 2020, to March 31, 2020, were enrolled. The inclusion criteria for patients were: (I) respiratory rate ≥30 per min, (II) pulse oxygen saturation at rest or without oxygen ≤93%, (III) PaO2/FiO2 ≤300 mmHg, (IV) pulmonary imaging shows that within 24–48 hours, the lesion has obviously progressed >50%, (V) age >60 years and complicated with severe chronic disease including hypertension, diabetes, coronary heart disease, malignancy cancer, structural lung disease, pulmonary heart disease, and immunosuppressed people. The patient who meet any of the above was enrolled. The patients with mild symptoms and transferred from other hospitals were excluded. There were fifteen patients who with mild symptoms did not receive oxygen therapy and 13 patients who were transferred from other hospitals. The rest 30 patients receiving standardized oxygen therapy in our unit were included in the study.

All the patients with severe symptoms also received same standardized treatment. The physicians used arbidol tablets and Chinese prescription LianhuaQingwen capsule for antiviral, moxifloxacin for anti-infective, glucocorticoid for anti-inflammatory, thymosin and gamma globulin for immunotherapy.

All procedures performed in this study involving human participants were in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (as revised in 2013), and this project was approved by the ethical committee of the Eastern Branch, Renmin Hospital of Wuhan University (Decision No. WDRY2020-K048). All the participants gave informed consent before taking part.

Standardized oxygen therapy nursing strategy

The standardized oxygen therapy nursing strategy focuses on the patient’s oxygenation. We assess oxygenation in real-time and start oxygen therapy at an earlier stage. This strategy comprehensively focuses on the initiation, upgrading, phased evaluation, and downgrading of oxygen therapy. Respiratory support therapy is downgraded as soon as the patient’s condition is improved, to avoid side effects and to waste resources, and to promote early rehabilitation of the patient (See Figure 1).

Data collection and definition

Baseline characteristics, symptoms, and finger pulse oxygen saturation were collected during hospitalization. The primary clinical symptoms of patients with COVID-19 included fever, nonproductive cough, dyspnea, myalgia, fatigue, and diarrhea (2). Oxygen saturation is the percentage of the oxygen amount (oxygen content) bound by hemoglobin in the maximum amount of oxygen amount (oxygen content) that can be bound by hemoglobin. Oxygen saturation measured through the distal skin of the digits or elsewhere is called noninvasive saturation, also known as pulse oxygen saturation. Patients’ data were collected from February 9, 2020, to March 31, 2020. The information on patients’ symptoms such as dyspnea, chest pain, fatigue, diarrhea and myalgia was obtained through oral inquiry of medical history. Pulse oxygen saturation data using Yuwell clip-type pulse oxygen meter YX301 for monitoring. All the data were collected by specific person when patients admitted and transferred out to ICU.

Statistic analysis

SPSS 23.0 software was used to analyze the data. General data were analyzed by gender, age, and past medical history. The symptoms of dyspnea, chest pain, fatigue, diarrhea, and myalgia were examined by the χ2 test, and the oxygen saturation in both groups was examined by paired sample t-tests.

Results

Analysis of patients’ general data

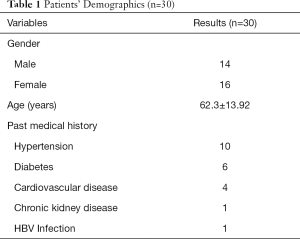

As shown in Table 1, the general data of the cohort is shown as follows: 14 males and 16 females; mean age 62.3±13.92 (years); hypertension (33.33%), diabetes (20.00%), cardiovascular disease (13.33%), chronic kidney disease (3.33%), and HBV infection (3.33%).

Full table

Clinical patient outcomes

In this study, the clinical outcomes of 30 patients receiving the standardized oxygen therapy nursing strategy were as follows: 27 patients (90.00%) were cured and discharged; 3 patients (10.00%) who continued to stay in hospital were stabilized with symptoms relieved. The oxygen saturation without oxygen therapy is over 96%. However, nucleic acid results are still positive.

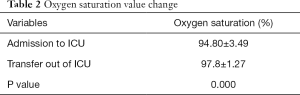

As shown in Table 2, the standardized oxygen therapy nursing strategy is associated with improved oxygenation of the patients. The fingertip oxygen saturation was 94.80%±3.49% at ICU admission and 97.8%±1.27% when transferred out of ICU after standardized oxygen therapy. A significant statistical difference was observed (P<0.005).

Full table

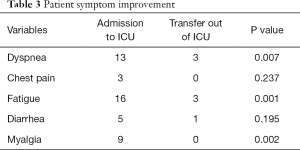

As shown in Table 3, receiving the standardized oxygen therapy nursing strategy may relieve patient symptoms. The symptoms of dyspnea, fatigue, and muscle aches of the patients were improved when transferred out of the ICU, compared with their condition when admitted to the ICU, with a significant statistical difference (P<0.05). There is no statistical difference in the symptoms of chest pain and diarrhea.

Full table

Discussion

The effects of standardized oxygen therapy nursing strategy (upgrading and downgrading of oxygen therapy) on relieving patient symptoms

Common symptoms of COVID-19 include fever, dry cough, myalgia, fatigue, dyspnea, and anorexia. Many patients initially showed atypical symptoms, including diarrhea or nausea (10). Previous studies have found that older patients with a past medical history are more likely to progress into critical patients (10), which also corresponds to the symptoms of the critical patients we have reported. For the critical patients who are elderly or have a past medical history, standardized oxygen therapy technology will be one of the main therapeutic measures, for the reason that appropriate oxygen therapy can reduce inspiratory resistance as well as patients’ work and oxygen consumption of breathing (11). The main mechanism of hypoxemia in COVID-19 patients is that inflammation damages alveolar epithelial cells and the lung capillary endothelial cells, causing pulmonary interstitial and alveolar edema, affecting the diffusion of oxygen. Another is the decrease of pulmonary surfactant, the increase of alveolar surface tension, leading to alveolar collapse, the number of alveoli that effectively participate in gas exchange is reduced, and the ratio of ventilation/blood flow is imbalanced (12). The standardized oxygen therapy nursing strategy reported in this study helps relieve the common symptoms. Our strategy emphasizes starting oxygen therapy at an earlier stage to implement various oxygen therapy technologies as early as possible, focusing on nursing and evaluation of treatment effects. Throughout treatment, the nurse’s concern about the patient’s primary symptoms was highlighted, and the nurse was emphasized on asking the patient about complaint symptoms while monitoring vital signs. The improvement of patient symptoms is also used as an indicator for the evaluation of patients’ lung rehabilitation exercise. Follow-up of integrated nursing measures according to different oxygen therapy cannot only ensure the effectiveness of treatment but also emphasize nursing observation throughout the whole process.

The effects of standardized oxygen therapy nursing strategy (upgrading and downgrading of oxygen therapy) on the improvement of patient oxygen saturation

The results of this study show that COVID-19 patients should take oxygen saturation as an essential nursing observation index. It is particularly significant for the clinicians to select a proper initial oxygen therapy measure, especially when dealing with immunocompromised patients (13,14). Related studies also found that the choice of upgraded oxygen therapy is also correlated with mortality (13). A standardized oxygen therapy strategy program has a positive effect on improving oxygen saturation in patients with COVID-19. The current guidelines on the application of oxygen therapy techniques are mostly focused on the sign for initiation and termination of oxygen therapy. While bedside care has played a more critical role for patients with COVID-19, therefore, nurses must acquire the criteria of use oxygen therapy strategy (upgrading and downgrading of oxygen therapy), carefully observing the patient’s oxygen saturation. Simultaneously, the nurse should also pay attention to the implementation of standardized operations of various nursing techniques, which will play an essential decisive role in improving patient outcomes. The strategy of nursing in this study emphasizes the delicacy management of nursing measures, and our whole program focuses on nurse-led airway management and adequate drainage of airway secretions, which confirms the nursing strategy has a positive effect on improving the oxygen saturation of patients.

Quality management of standardized oxygen therapy nursing strategy

The standardized oxygen therapy nursing strategy is a nurse-led management strategy. According to Mai et al. (15), nurse-led nursing can supply more effective treatment and patient care. To ensure the effectiveness and correctness of the implementation of the entire nursing strategy during the process, the nurse practitioner must pay attention to continuous quality improvement. In this strategy, nurse practitioners must participate in quality management throughout the whole process, including the upgrading, downgrading, and termination indications, as well as the implementation of various detailed steps of nursing strategies. If defects are found during the quality supervision, the quality management team should be organized to analyze the causes of defects, improve the implementation, and conduct continuous quality supervision. The closed-loop management enables the strategy to implement and operate and ensure the effectiveness of clinical work. Not only does our quality management focus on the clinical outcomes, but it also concerns the prevention and control of the spread of COVID-19, especially the detailed management of aerosol infection. We implement this strategy to ensure zero infection for all our medical staff.

However, this study is a single-center retrospective observational study with a small sample size. Therefore, the results of the study need to be further confirmed by large-scale multi-center studies.

Conclusions

The standardized oxygen therapy nursing strategy for patients with COVID-19 emphasizes the nursing measurement, which focuses on the patient’s oxygenation. It is led by nurses and starts oxygen therapy at an earlier stage. This strategy not only improves the clinical outcomes of critical patients but also effectively reduces the infection risk of medical staff while emphasizing nursing quality management.

Acknowledgments

Funding: Fudan University for the “Double First-Class Key Discipline Construction” (2018-40-22).

Footnote

Reporting Checklist: The authors have completed the STROBE reporting checklist. Available at http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/apm-20-1272

Data Sharing Statement: Available at http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/apm-20-1272

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/apm-20-1272). The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. All procedures performed in this study involving human participants were in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (as revised in 2013), and this project was approved by the ethical committee of the Eastern Branch, Renmin Hospital of Wuhan University (Decision No.WDRY2020-K048). All the participants gave informed consent before taking part.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- World Health Organisation Novel Coronavirus (COVID-19) Situation (EB/OL). Available online: https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/coronaviruse/situation-reports/20200401-sitrep-72-covid-19.pdf?sfvrsn=3dd8971b_2

- Huang C, Wang Y, Li X, et al. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet 2020;395:497-506. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Chen N, Zhou M, Dong X, et al. Epidemiological and clinical characteristics of 99 cases of 2019 novel coronavirus pneumonia in Wuhan, China: a descriptive study. Lancet 2020;395:507-13. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Chinese Research Hospital Association of Critical Care Medicine, Youth Committee of Chinese Research Hospital Association of Critical Care Medicine. Chinese experts consensus on diagnosis and treatment of severe and critical coronavirus disease 2019 (revised edition). Chin Crit Care Med 2020;32:269-74.

- Yang X, Yu Y, Xu J, et al. Clinical course and outcomes of critically ill patients with SARS-CoV-2 pneumonia in Wuhan, China: a single-centered, retrospective, observational study. Lancet Respir Med 2020;8:475-81. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- ARDS Definition Task Force, Ranieri VM, Rubenfeld GD, et al. Acute respiratory distress syndrome: the Berlin Definition. JAMA 2012;307:2526-33. [PubMed]

- Meng L, Qiu H, Wan L, et al. Intubation and Ventilation amid the COVID-19 Outbreak: Wuhan's Experience. Anesthesiology 2020;132:1317-32. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Jin YH, Cai L, Cheng ZS, et al. A rapid advice guideline for the diagnosis and treatment of 2019 novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) infected pneumonia (standard version). Mil Med Res 2020;7:4. [PubMed]

- Sorbello M, El-Boghdadly K, Di Giacinto I, et al. The Italian coronavirus disease 2019 outbreak: recommendations from clinical practice. Anaesthesia 2020;75:724-32. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wang D, Hu B, Hu C, et al. Clinical Characteristics of 138 Hospitalized Patients With 2019 Novel Coronavirus-Infected Pneumonia in Wuhan, China. JAMA 2020;323:1061-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Shepard JW Jr, Burger CD. Nasal and oral flow-volume loops in normal subjects and patients with obstructive sleep apnea. Am Rev Respir Dis 1990;142:1288-93. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gao Y. Therapeutic strategies for COVID-19 based on its pathophysiological mechanisms. Chinese Journal of Pathophysiology 2020;36:568-572,576.

- Kang BJ, Koh Y, Lim CM, et al. Failure of high-flow nasal cannula therapy may delay intubation and increase mortality. Intensive Care Med 2015;41:623-32. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ozyilmaz E, Ugurlu AO, Nava S. Timing of noninvasive ventilation failure: causes, risk factors, and potential remedies. BMC Pulm Med 2014;14:19. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Mai A, Braun J, Reese JP, et al. Nurse-led care versus physician-led care in the management of rheumatoid arthritis and psoriatic arthritis (StaerkeR): study protocol for a multi-center randomized controlled trial. Trials 2019;20:793. [Crossref] [PubMed]

(English language editor: J. Chapnick)