Medical assistance in dying (MAiD) in Canada: practical aspects for healthcare teams

Background

The purpose of this paper is to document some of the practical aspects of the implementation of assisted dying in Canada during the four years December 2015 to December 2019. The three authors are all physicians who have provided assisted dying during this time. We discuss the various models of care across the country, early and ongoing challenges as well as some of the solutions.

In this paper, we will use the term assisted dying to refer to the administration of a lethal substance at the explicit request of a competent adult, regardless of the global jurisdiction in which it occurs or the terminology otherwise used in that jurisdiction. In Canada, the term medical assistance in dying (MAiD) includes both options of self- administration of an oral medication (not allowed in Quebec) or clinician-administration of an intravenous regime. MAiD is only allowed to be facilitated by either a medical doctor or a nurse practitioner (1).

In order to understand MAiD in Canada, it is important to briefly review how Canada came to legalize assisted dying and three factors specific to the Canadian context. Firstly, we have the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms, a constitutional document, that outlines the fundamental freedoms and democratic rights of all citizens (2). It includes the right to life, liberty and the security of person, and it is this framework that was used to successfully challenge the previously existing, universal ban on assisted dying. The decriminalization of MAiD in Canada came through a high court decision involving the constitutional rights of patients, not through government led legislation, which only followed afterwards to regulate the practice (1). Secondly, Canada has a policy of universal health care, and MAiD is a fully covered medical service throughout the ten provinces and three territories. Thirdly, it is important to note that while our criminal code is federally effective, health care is administered provincially in Canada. This means that while our law on assisted dying applies nationally, how health care is implemented and regulated may be different from one province to another. This leads to a number of important, ongoing, regional distinctions in MAiD nationally. The most noteworthy distinction involves the history of assisted dying in the province of Quebec where assisted dying was legalized in December 2015. As health care is administered provincially and assisted dying was considered health care, Quebec undertook their own study of the issue and regulated its practice earlier than the rest of Canada. The Quebec law on eligibility criteria is currently more restrictive than the rest of Canada but the recent Truchon decision will lead to a change in 2020 (3).

The process to access an assisted death in Canada involves a written, witnessed request by a patient followed by two assessments of eligibility by two independent clinicians. If both agree the patient meets all eligibility criteria, the patient may access an assisted death after a 10-day reflection period. In order to be eligible, a patient must meet the following criteria:

- The person must be an adult, defined as 18 years of age or older;

- The person must be eligible for Canadian health care;

- The request must be voluntary and free of any coercion;

- The person must have a grievous and irremediable condition. This is further defined in the current legislation as requiring all of the following to be true:

- Have a serious and incurable illness, disease or disability;

- Be in an advanced state of decline in capability;

- The decline must be irreversible;

- The patient must be suffering in a way that they deem intolerable;

- The natural death of the person is considered reasonably foreseeable (defined by the assessing clinician).

- The person must have the capacity, including a full understanding of options and possible outcomes, to make this request.

Current state

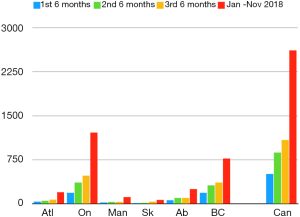

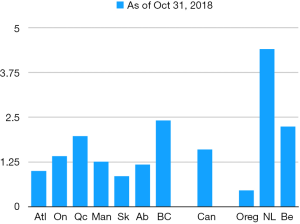

The most recent national data available from Health Canada is from October 31, 2018, only 28 months after the law was amended (4). Figure 1 shows the uptake of MAiD in various regions in Canada throughout the first 28 months. Figure 2 measures regional MAiD as a percentage of annual deaths, allowing comparison to other jurisdictions where assisted dying is available, and has been for decades in some form. This data shows that by October 2018, 1.6% of all deaths in Canada were by assisted dying. British Columbia led the country in requests and provisions with 2.4% of annual death by assisted dying (and one BC health region had over 5%) (5). Using provincial reports, we now estimate that during the four years, December 2015 to December 2019, approximately 13,000 Canadians have had assisted deaths. According to Health Canada’s fourth interim report, men and women are accessing assisted dying in virtually equal numbers (4). The average age of someone receiving MAiD is 73, and assisted dying occurs at home, in hospital, in hospice, on palliative care wards, in nursing homes and in assisted living residences. The majority of people receiving MAiD have cancer (64%), end-stage organ failure (17%), or neurological disease (11%). In Canada, we cannot use death certificate data to understand the uptake of assisted dying because some provinces require “MAiD” to be listed as the cause of death and others forbid this for privacy reasons (6).

Regionalization

In the same way that uptake of MAiD has varied widely across the country, so have the models of care. Since health care is administered provincially-and most of the 10 provinces have further divided care into regional health authorities or health networks, there are a number of different models of care. Oversight has been delegated to each of the provinces and they have chosen different methods. We give three specific examples here:

Quebec developed province-wide standardized care with a pre-printed, mandatory prescription for the medications to be used for assisted dying. There are standard forms to complete, and additional provincial regulations including that only IV drugs may be used for assisted dying. All hospitals in Quebec are required to allow MAiD on their premises. Nurse practitioners are not allowed to provide this care in Quebec. Quebec set up an 11-member Commission des Soins de Fin de Vie (End of Life Care Commission) to posthumously review every case of assisted dying and to send a summary of that information to Health Canada. All cases are also reviewed by the Conseil des Médecins, Dentistes et Pharmaciens (in hospital) or the College des Médecins du Québec (in community). Each health authority within Quebec has a Groupe Interdisciplinaire de Support (support group) for MAiD providers.

Ontario has 14 separate health networks and there are many models of care. Funding for MAiD care varies widely within the province. There are no standard prescriptions or forms. There is a province-wide, central phone number that patients and non-providing clinicians can use to access providers of MAiD. Some health networks have care coordinators and inter-disciplinary teams seeing each patient. These coordinators help gather medical records, make appointments for assessments, organize the required forms, and arrange IV access, amongst other tasks. Others health networks require the clinician to coordinate each of these tasks themselves. All cases of MAiD in Ontario are reviewed for oversight by the Office of the Chief Coroner before required data is sent to Health Canada.

British Columbia has six health authorities and each has a coordinating office that connects patients with providers, provides general information for patients and clinicians, helps organize patient request forms, and recruits nursing support. Forms and prescriptions are standardized across the province. All cases are reviewed by the provincial Ministry of Health before required data is reported to Health Canada.

This decentralization of MAiD care has left some areas of Canada with no care coordination and effectively no oversight. In order to provide the best care to patients requesting MAiD, there should be care coordination centres in each province or health region. They should provide accurate information to patients and non-participating clinicians. They should help with logistics to reduce excessive burden on patients and clinicians. Best models of care would also incorporate quality improvement programs.

Challenges and solutions

Access

When we consider access to MAiD, we must at the same time consider the access to other end-of-life care options, such as palliative care and residential hospices. The Canadian government announced additional funding for palliative care at the time the assisted dying law came into force (7). As with other medical care, it is easier to access the full spectrum of end of life care in urban environments and if one is able to advocate for oneself. Large urban centres have specialized palliative care available in hospitals, residential hospices and in the community without cost to the patient. Unfortunately, this care may not always be available in a timely or adequate manner in rural areas. People who are socially or economically disadvantaged often also have less access to all forms of end of life care (8).

When the law changed in 2016, the professional licensing bodies were slow to publish their standards and regulations. Lawyers advising clinicians were not surprisingly very conservative and there were no available training programs for clinicians (9). This led some physicians to be wary of providing assisted deaths (10). Nurse practitioners were delayed even longer (11). There was active opposition by some organizations, such as some physician residency training programs forbidding trainees from participating in assisted deaths and some hospices forbidding their physicians from doing assessments or provisions (9). Over the years, there has been more training and mentoring available, both to trainees and practicing clinicians. Training is now provided by on-line and in-person workshops; by universities; by medical associations and by health authorities (12). There is no accreditation required to provide assisted deaths in the community, but special privileges to provide MAiD are required for provision in some hospitals and other health care facilities. The number of providers has increased along with the number of people requesting MAiD since 2016.

There is still a shortage of providers of assisted dying in Canada and this is more acute in rural areas (10). One of the ways this inequity has been reduced is by doing some of the initial assessments through telemedicine (i.e., video-conferencing) (13). In some provinces, this is only allowed using specific health authority equipment, and only permitted for one of the two required assessments. Other provinces require an additional health professional to be present with the patient in order to witness the assessment. People who live in rural areas are used to the need to travel for specialized services not available in their area, but people requesting MAiD are at the end of life and usually have great difficulty travelling. This means busy clinicians may have to travel long distances to meet patients in their rural communities and this travel is not always reimbursed.

All provinces provide the MAiD medications at no expense to the patient, but the medications are not always available due to some pharmacists not being willing to dispense or stock them. Canada had no adequate barbiturates available for oral administration until recently.

The other important issue in access is the availability of accurate information for patients. There are now MAiD coordination centres in most health authorities helping patients get the necessary information and connecting them to assessors and providers. People at the end of life are very vulnerable and may have no one advocating for their rights. This means that there are still problems with some patients asking for an assisted death, but not being able to negotiate the process, not being able to get the request form or the independent witnesses, and not knowing how to find clinicians to do the assessments and provision (14,15).

Relationships

The Canadian Association of Palliative Care issued a statement that “MAiD is not part of hospice palliative care” (16). Many palliative care clinicians follow their association’s position and do not assess or provide MAiD. However, there are a number of MAiD providers who are also palliative care specialists and are able to offer seamless end of life care (17). The relationships between MAiD providers and palliative care providers vary from collegial with good communication about their shared patients to hostile and fractious. When both palliative care providers and MAiD providers focus on providing patient-centered care, these relationships improve (17,18).

Most MAiD providers in Canada are not the patient’s primary treating clinician and there have been problems with relationships between MAiD providers and the other clinicians caring for the patient (5,19,20). The law was described by the then Minister of Justice as “flexible” and therefore different clinicians may disagree about who is truly eligible. Psychiatrists trained to prevent suicide and often have difficulty accepting that some people prefer an assisted death to accepting their physical deterioration from a terminal illness (19,20). As long as two clinicians approve a patient’s decision, they can receive MAiD, even if other clinicians have assessed and not approved. These disagreements occasionally lead to formal complaints and a great deal of stress. Nurses, social workers and other staff may be very involved with the patient’s care and communication with all members of the team is important (21-24).

Most patients arrive at their assessment having discussed their choice with their loved ones and have their full, if sometimes reluctant, support. Some are estranged from family or have not informed close family members and want to keep it a private matter. Although each Canadian has the right to make the decision for MAiD for themselves, we know that these complicated situations can lead to increased risk for the providers, because an angry surviving family member is more likely to make formal complaints against the provider. More importantly, these situations of lack of transparency may lead to more complicated grieving for the survivors (25). Whenever possible, providers try to negotiate fulsome communication before the death. Anecdotally, this often leads to important, meaningful conversations and often reconciliation. Sometimes, the act of setting a date for death can trigger communication that might otherwise have been avoided.

Anti-choice issues

Many health care facilities in Canada, including hospitals, hospices and care homes, are operated by faith-based organizations, while being partially or fully funded by public taxes. Only in Quebec are all hospitals required to provide MAiD. Elsewhere in Canada, patients in many faith-based and other abstaining facilities must be transferred out for MAiD. This has caused inconvenience for some and immense suffering for others (26). Generally, patients in hospices or hospitals at the end of life are frail and find the transfers very difficult both physically and emotionally. Patients living in care homes often feel that they deserve to be able to die in the familiar environment of their legal home. Providers and care coordinators have found a variety of not wholly satisfactory solutions to this ongoing problem (19-21).

In the federal assisted dying law it is clear that no clinician can be forced to provide MAiD (1). It is logical and ethical that no clinician should be forced to write a lethal prescription or administer a lethal substance, but some conscientious objectors have suggested that in their opinion, objection to the participation in MAiD also extends to the referral of patients or provision of the necessary information that facilitates access to MAiD (27). This stance led to a court challenge in Ontario in which the judge ruled that under professional guidelines of conduct, doctors must make “effective referrals” (28). Most of the provincial regulatory Colleges (who license clinicians) have standards that say that physicians who object to MAiD are “required to provide an effective transfer of care for their patients” (29). This has not prevented clinicians from deliberately obstructing patients. There remain doctors, nurse practitioners and other healthcare professionals who bloc access to assisted dying and pharmacists who refuse to dispense the prescribed drugs. There are nurses who refuse to care for patients who have requested MAiD, and even cleaning staff who have refused to clean patient rooms (19,20,30-32).

Logistics

Canadian law allows the choice of a self-administered oral medication or clinician administered intravenous (IV) drugs. Some provinces require discussion of both options (BC) and others restrict MAiD to IV only (Quebec). Of the approximately 13,000 MAiD deaths that took place in Canada between December 2015 and December 2019, only 16 were reported to be self-administered oral medication (33). End-of life patients often have difficult IV access. Providers come from many disciplines in medicine and most require the assistance of another professional to establish IV access. Anecdotally, this adds another barrier to care in finding and scheduling an appropriately trained person who is willing to do this. Approximately half of MAiD cases occur in hospitals with such professionals onsite. Some patients have needed to be transported from home to hospital to get IV access (19-21).

In 2016, Canada had no supply of the barbiturates commonly used in Europe for MAiD. Only since 2018 was secobarbital for oral administration made available. The standard IV protocols for MAiD vary, but most commonly include a combination of midazolam, propofol and rocuronium with some routinely adding lidocaine and/or bupivacaine. These drugs are used for general anesthetics and are readily available in hospitals, but can be very difficult to obtain through community pharmacies (19,20). Regulations require clinicians to personally obtain the drugs from a pharmacist and for both professionals to sign the transfer form confirming transfer of medication. In most provinces, regulations also require that providers take a second, back-up kit of medication to each provision and must return all unused medications in person. This requirement can add additional hours of time to the MAiD procedure (19,20).

Witnesses to the written request for MAiD in Canada must be independent, that is, not medical care givers, personal care givers or anyone able to benefit financially from the death of the patient (1).

By the end of life, many people no longer have anyone in their lives except their care givers and family. For those accessing MAiD they may not want anyone else to know about their choice so there are often no obviously suitable witnesses.

Dying with Dignity Canada has developed a volunteer witness program across the country to help with this problem (15,34).

The majority of physicians in Canada are paid by fee-for-service through provincial insurance plans and the majority of nurse practitioners are paid by salary. At the beginning, there were no applicable fee codes for physicians and no mechanisms to pay nurse practitioners. This meant some clinicians provided this care without compensation and others decided to stop providing (10). This situation has improved but continues to be a significant issue amongst nurse practitioners (11).

MAiD in the time of the COVID19 pandemic

The first drafts of this paper were written in 2019 before Canada experienced any effects of the global COVID-19 pandemic. At the time of this revision, in May 2020, Canada has seen more than 80,000 cases and more than 6,000 deaths due to COVID-19 (35). Just prior to the pandemic, the government tabled significant amendments to the current federal MAiD law (36). Suggested changes included removing the eligibility requirement for a patient’s death to be reasonably foreseeable, reduction of required witnesses to one individual who could be a paid care provider and the removal of the 10-day mandatory reflective period after a formal written request. In cases of patients where their death was not foreseeable, there is the suggestion of a 90-day mandatory waiting period and additional safeguards to be applied.

Currently, parliament is understandably focused on mitigating the effects of the global pandemic, and it is unclear what will happen to the proposed legislation (37). At the same time, several provincial regulators have moved quickly to make allowances for both MAiD clinician and patient safety during the pandemic, allowing more telemedicine where it was previously not allowed and the acceptance, in many regions, of the virtual (via videoconferencing) witnessing of signatures for the written request for MAiD (38). Anecdotally, the authors have noticed that some of our patients have requested to die earlier because they fear getting COVID and/or because they can no longer spend time with loved ones due to pandemic restrictions.

Despite living in a time of some uncertainty, the authors believe the practice of MAiD in Canada will continue to evolve.

Acknowledgments

Funding: None.

Footnote

Provenance and Peer Review: This article was commissioned by the Guest Editors (Nancy Preston, Sheri Mila Gerson) for the series “Hastened Death” published in Annals of Palliative Medicine. The article has undergone external peer review.

Peer Review File: Available at http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/apm-19-631

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/apm-19-631). The series “Hastened Death” was commissioned by the editorial office without any funding or sponsorship. The authors have no other conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- Government of Canada. An Act to amend the Criminal Code and to make related amendments to other Acts (medical assistance in dying). 2016.

- Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms. [cited 2020 Mar 1]. Available online: https://laws-lois.justice.gc.ca/eng/Const/page-15.html

- Truchon c. Procureur général du Canada. QCCS 3792 (“Truchon”) 2019.

- Health Canada. Fourth Interim Report on Medical Assistance in Dying in Canada [Internet]. Health Canada; 2019. Available online: https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/publications/health-system-services/medical-assistance-dying-interim-report-april-2019.html

- Robertson WD, Beuthin R. A Review of Medical Assistance in Dying on Vancouver Island July 2016-July 2018. Available online: https://www.islandhealth.ca/sites/default/files/2018-11/maid-report-2016-2018.pdf

- Brown J, Thorpe L, Goodridge D. Completion of Medical Certificates of Death after an Assisted Death: An Environmental Scan of Practices. Healthc Policy 2018;14:59-67. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Canadian Cancer Society. Federal budget investment in home and palliative care a win for cancer patients. 2017 Mar 22. Available online: https://www.cancer.ca/en/about-us/for-media/media-releases/national/2017/federal-budget-announcement/?region=on

- Shaw J, Harper L, Preston E, et al. Perceptions and Experiences of Medical Assistance in Dying Among Illicit Substance Users and People Living in Poverty. Omega (Westport) 2019. [Epub ahead of print].

- MacDonald S, LeBlanc S, Dalgarno N, et al. Exploring family medicine preceptor and resident perceptions of medical assistance in dying and desires for education. Can Fam Physician 2018;64:e400-406. [PubMed]

- Walsh D, Bulger K, McGean R, et al. Engaging Physicians to Participate in Medical Assistance in Dying in Southern Alberta. Abstr Present. Available online: http://hemlockaid.ca/?page_id=198

- Beuthin R, Bruce A, Scaia M. Medical Assistance in Dying (MAiD): Canadian Nurses’ Experiences. Nurs Forum 2018;53:511-20. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wiebe E, Green S, Schiff B. Teaching residents about medical assistance in dying. Can Fam Physician 2018;64:315-6. [PubMed]

- Dion S, Wiebe E, Kelly M. Quality of care with telemedicine for medical assistance in dying eligibility assessments: a qualitative study. CMAJ Open 2019;7:E721-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Beuthin R. Cultivating Compassion: The Practice Experience of a Medical Assistance in Dying Coordinator in Canada. Qual Health Res 2018;28:1679-91. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Praslickova Z, Kelly M, Wiebe E. The Experience of Volunteer Witnesses for Medical Assistance in Dying (MAiD) Requests. Death Stud 2020. [Epub ahead of print].

- Canadian Hospice Palliative Care Association. CHPCA and CSPCP - Joint Call to Action. 2019. Available online: https://www.chpca.ca/news/chpca-and-cspcp-joint-call-to-action/

- Wales J, Isenberg IS, Wegier P, et al. Providing Medical Assistance in Dying within a Home Palliative Care Program in Toronto, Canada: An Observational Study of the First Year of Experience. J Palliat Med 2018;21:1573-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Downar J, Fowler RA, Halko R, et al. Early experience with medical assistance in dying in Ontario, Canada: A cohort study. CMAJ 2020;192:E173-81. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Shaw J, Wiebe ER, Nuhn A, et al. Providing Medical Assistance in Dying: Practice Perspectives. Can Fam Physician 2018;64:e394-9. [PubMed]

- Khoshnood N, Hopwood MC, Lokuge B, et al. Exploring Canadian Physicians’ Experiences Providing Medical Assistance in Dying: A Qualitative Study. J Pain Symptom Manage 2018;56:222-229.e1. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Pesut B, Thorne S, Greig M, et al. Ethical, policy, and practice implications of nurses’ experiences with assisted death: A synthesis. ANS Adv Nurs Sci 2019;42:216-30. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Schiller CJ, Pesut B, Roussel J, et al. But it’s legal isn’t it? Law and ethics in nursing practice related to medical assistance in dying. Nurs Philos 2019;20:e12277 [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bruce A, Beuthin R. Medically Assisted Dying in Canada: “Beautiful Death” Is Transforming Nurses’ Experiences of Suffering. Can J Nurs Res 2019; [Epub ahead of print]. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Antifaeff K. Social Work Practice with Medical Assistance in Dying: A Case Study. Health Soc Work 2019;44:185-92. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Trouton K, Beuthin R, Thompson M, et al. Attitudes and expectations regarding bereavement support for patients, family members, and friends: Findings from a survey of MAiD provider. BC Med J 2020;62:18-23.

- Blackwell T. B.C. man faced excruciating transfer after Catholic hospital refused assisted-death request. National Post 2016 Sep 27. Available online: https://nationalpost.com/news/canada/b-c-man-faced-excruciating-transfer-after-catholic-hospital-refused-assisted-death-request

- Pesut B, Thorne S, Greig M. Shades of grey: Conscientious objection in medical assistance in dying. Nurs Inq 2020;27:e12308 [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Grant K. Ontario’s top court rules religious doctors must offer patients an ‘effective referral’ for assisted dying, abortion. The Globe and Mail 2019 May 15. Available online: https://www.theglobeandmail.com/canada/article-religious-doctors-must-make-referrals-for-assisted-dying-abortion/

- College of Physicians and Surgeons of British Columbia. Practice Standard: Medical Assistance in Dying 2020. Available online: https://www.cpsbc.ca/files/pdf/PSG-Medical-Assistance-in-Dying.pdf

- Holmes S, Wiebe ER, Shaw J, et al. A Qualitative Study Exploring the Journey of Supporting a Loved One through a Medically-Assisted Death in Canada. Can Fam Physician 2018;64:e387-93. [PubMed]

- Nuhn A, Holmes S, Kelly M, et al. Experiences and perspectives of people who pursued Medical Assistance in Dying (MAiD) in Vancouver, Canada. Can Fam Physician 2018;64:e380-386. [PubMed]

- Verweel L, Rosenberg-Yunger ZRS, Movahedi T, et al. Medical assistance in dying: Examining Canadian pharmacy perspectives using a mixed-methods approach. Can Pharm J (Ott) 2018;151:121-32. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Harty C, Chaput AJ, Trouton K, et al. Oral medical assistance in dying (MAiD): informing practiceto enhance utilization in Canada. Can J Anaesth 2019;66:1106-12. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Find An Independent Witness For Medical Assistance In Dying [Internet]. Dying with Dignity Canada. [cited 2020 Apr 17]. Available online: https://www.dyingwithdignity.ca/witness_program

- Government of Canada. Coronavirus disease (COVID-19): Outbreak update [Internet]. Government of Canada. [cited 2020 Apr 17]. Available online: https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/diseases/2019-novel-coronavirus-infection.html?&utm_campaign=gc-hc-sc-coronaviruspublicedu2021-2021-0001-9762248618&utm_medium=search&utm_source=google-ads-99837326356&utm_content=text-en-428935858540&utm_term=covid

- Ibbitson J. Emergency wage subsidy approved, but parties dispute how Parliament should meet next. The Globe and mail. 2020 Apr 11 [cited 2020 Apr 17]; Available online: https://www.theglobeandmail.com/politics/article-house-approves-emergency-wage-subsidy-dispute-how-to-meet-in-future/

- Bryden J. Feds introduce bill dropping some restrictions on assisted dying. National Newswatch [Internet]. 2020 Feb 24 [cited 2020 Apr 17]; Available online: https://www.nationalnewswatch.com/2020/02/24/feds-to-introduce-bill-dropping-some-restrictions-on-assisted-dying/#.XpTP13DsaUm

- College of Physicians and, Surgeons of British Columbia. Covid-19 Updates. College of Physicians and Surgeons of British Columbia. 2020 [cited 2020 Apr 1]. Available online: https://www.cpsbc.ca/news/COVID-19-updates