Perspectives of people accompanying a person during voluntary stopping eating and drinking: a convergent mixed methods study

Introduction

Voluntary stopping eating and drinking (VSED) is an emerging global topic (1-8). Data from the Netherlands (9,10) and Switzerland (11,12) show that between 0.4% and 2.1% of annual deaths are attributable to VSED; unreported cases are likely (3,11,12). VSED is an option when a person consciously and voluntary decides to bring about death by stopping eating and drinking (1,13). It differs significantly from other forms of food refusal (14), where the person has no intention of dying (13,15,16). In Switzerland, VSED was first included in the Swiss Academy of Medical Sciences’ (SAMS) guidelines for “Management of dying and death” in 2018 (17). The guidelines clearly distinguished three situations.

The first situation describes people whose life expectancy is limited to a few days or weeks due to an illness (17). In this phase, feelings of hunger and thirst often decrease and the desire to shorten the dying process can arise (18), which is a generally accepted action in Switzerland (17), Germany (19), Austria (2), and the Netherlands (20).

The second situation concerns the person’s judgement. The guidelines (2,17,19,20) equally emphasize that the “voluntariness” in VSED presupposes a person’s ability to make decisions (1,13); if that ability is limited (e.g., in the early stages of dementia), it must be clarified exactly how the situation should be assessed (2,17,19,20). There are currently international scientific discussions (21-27) on whether a decision once made by a person with decision-making competence should still apply if this person loses the capacity in the further course of his or her life. The SAMS (17,28) explicitly rejects such behavior; food and liquid must be offered in any case, but not forced.

The third situation focuses on people without a terminal illness (17). Between 24% and 29% (1,9,29) of all people who follow the VSED path do not have a terminal disease. The unbearable suffering of those people is described as life fatigue, fullness of life, the senselessness of continuing to live, and low quality of life (1,29). In Germany and Austria, these situations are not covered by guidelines (2,19). In the Netherlands, no distinction is made between terminally ill and healthy people; the desire to die and the ability to judge are central (20). In Switzerland, the person’s motives and health status are considered, but the health professionals’ opinions are decisive (17).

Internationally, controversial discussions (7,21,30,31) on VSED classification (suicide or something else) and the legitimacy of accompaniment are ongoing, but a liberal stance has been adopted in Switzerland, similar to that in the Netherlands (20). Depending on the person’s health condition and the health professionals’ discretion, accompaniment is possible, since Swiss law allows that choice if the wish to die persists. However, a person has no binding right to accompaniment (Article 115 Swiss Penal Code). This leads to questions about what health professionals themselves think about VSED.

Quantitative studies with health professionals have confirmed that VSED is an internationally known phenomenon. Many participants had accompanied people during VSED; overall, patients are granted the right to medical and nursing care, and VSED is often considered an autonomous and “good” way to die (1,8,11,12,32). Although there are few qualitative studies (13), previous research indicated that accompanying a person during VSED is an individual decision (33), and that there is an implicit or unspoken form of VSED where the person does not talk about their intention or even hides it from others (14). The existing evidence is not sufficient to derive practical recommendations for health professionals.

Therefore, we aim to apply a mixed-methods design to explore the VSED knowledge and experience of Swiss family physicians and heads of outpatient and long-term care facilities, and to explain the current professional culture and handling of VSED as an emerging phenomenon. To the best of our knowledge, no previous mixed-methods studies on VSED have been conducted. We present the following article in accordance with the MDAR reporting checklist (available at http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/apm-20-1339).

Methods

Study design and research paradigm

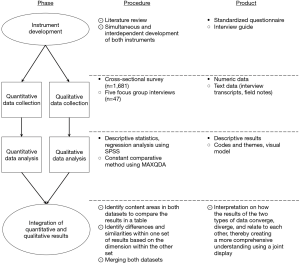

A convergent mixed methods study was chosen to answer the research question. As described in our study protocol (34) we conducted a national, cross-sectional survey and focus group interviews (Figure 1).

By integrating the exploratory and explanatory research strands (35), the contradictory aspects and open questions could be answered using abduction (36,37). The limitations of each research approach are balanced by the strengths of the other, and the combined strengths of both approaches lead to an extension of knowledge (38). The study design was directed by Dewey’s pragmatism, in which knowledge is continually re-generated by an oscillating movement between action and experience (39). Quantitative and qualitative data were collected simultaneously, with equal priority (40,41).

Rationale

The rationale for using a convergent mixed-method study was that the instruments’ development could be carried out simultaneously to ensure comparable methodological data sets. The approach allowed us to explore and explain the breadth and depth of the VSED phenomenon, especially the data integration it provides when the unexpected occurs, which can relativize the separate analyses. This approach promoted examining the national appearance and importance of VSED in Switzerland to better understand the phenomenon (42).

Design, participants and statistical analysis of the survey

A cross-sectional survey was conducted, including heads of outpatient and long-term care facilities, and family physicians in Switzerland. All three professions are very well organized through professional organizations. We took advantage of this and asked the management of the individual professional organizations whether they would support us in sending the questionnaires to the target groups and received their approval from all of them. We have invited a total of 4,589 health professionals (1,562 heads of long-term care; 1,616 heads of outpatient care, and 1,411 family physicians) in a staggered invitation between January 2017 and July 2018. Due to the recruitment strategy it is likely that participants who have already participated in the focus groups in 2016 will also be invited to participate in the survey. Due to the anonymous survey, however, we are not able to determine this. This is the case for at least 29 of the 47 participants in the focus groups who have the same profession as those surveyed.

The questionnaire for the survey and the interview guides for the qualitative interviews were developed simultaneously. In February 2016, a literature search was conducted in the following databases: PubMed, EBSCOhost CINAHL, Ovid PsychINFO, followed by an open search on the internet. Literature-based categories were formed to capture the phenomenon. Subsequently, questions were formulated and assigned to the research strand. Care was taken to ensure that similar questions were recorded both quantitatively for the questionnaire and qualitatively for the interview guide. The questionnaire was tested for intelligibility and manageability using a standard pre-test (43). After revision, the questionnaire was validated in two rounds using the content validity index (CVI) (44,45). All items had an item-CVI value greater than 0.90 and a scale-CVI of 0.97, which corresponds to excellent values. The literature review, and the development, psychometric testing (43-45) and the forward/backward translation (46) (from German into French, Italian, and English) of the questionnaire and the questionnaire itself has been published (47). A questionnaire with 41 items was developed to record the occurrence of the VSED and the experiences, attitudes and stances about it. The answers are given in free text fields and on five-point Likert scales.

The questionnaire was created online based on the survey software Questback (EFS 10.9). On the front page, the project and its objectives were described. Participation was voluntary and anonymous, and the participants had to actively give their consent to the study. Due to the low response rate among family physicians, which is described in more detail elsewhere (11), we created a paper-and-pencil questionnaire. The answered questionnaires were scanned and then read in, edited and exported as SPSS files using the EVASYS software.

Descriptive analysis was conducted using SPSS (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA; Version 25 and 26). To describe participants, and the attitudes and professional stance of the participants, appropriate statistical methods were used, such as means, standard deviations, percentages, and frequencies. Missing values were coded as such and automatically excluded from the analysis. The number of missing values in the analyses is indicated by the number of values included.

Design, participants and data analysis of the focus group interviews

We conducted a qualitative focus group study. We used a constructivist grounded theory methodology (48), that supports the inductive, emergent and constant comparative approach (49). The grounded theory is particularly suitable for phenomena whose conceptual framework has not been clearly identified and for which there is a lack of understanding to development a theory about VSED. The grounded theory was underpinned by a pragmatic philosophical perspective, which assumes that our knowledge is developed through our actions and interactions, which are shaped and developed by our social environment (39). For pragmatic research reasons the theoretical sampling as an instrument to reach theoretical saturation could not be performed.

In autumn 2016, 50 people involved in accompanying a person during VSED were invited for focus group interviews. The invitation to the focus groups followed an expert meeting organised by “Palliativ Zug” (www.palliativ-zug.ch). At each meeting one topic is discussed intensively with the participants of the meeting. The participants are either practitioners with a focus on palliative care, work in politics, are relatives of palliative patients or are affected themselves. On this day VSED was the main topic of discussion. All participants (n=50) of the meeting were invited to the focus groups, 47 of whom took part. One participant found it unpleasant to talk about the topic in a focus group, two participants did not have time. The interview guides were developed simultaneously with the questionnaire, after reviewing the literature described above. We performed five focus groups (50), starting with an open question, in which participants were asked to talk freely about their attitudes, experiences and stances regarding voluntary stopping of eating and drinking. As soon as the flow of speech stagnated, impulses were given to discuss the perspective of the person willing to die, relatives or health professionals; to talk about communication about voluntary stopping of eating and drinking or about the unspoken or unrecognized form of refusal to eat. Five focus group interviews were conducted and after the consent of the participants were obtained, the focus groups were digitally recorded and transcribed verbatim. Focus groups are suitable for exploring experiences and attitudes within the group on a given topic, taking into account the participants’ interaction and group dynamics and incorporating them into the analysis (51). Each interview lasted 60 minutes. Field notes were taken during and immediately after the focus groups. The data were evaluated inductively using a modified ground theory approach that uses guidelines for systematic, theory-driven data analysis by Charmaz (48). MAXQDA (Analytics Pro 2018) software was used to simplify data coding and memo writing. Each interview was read and re-read in its entirety, one after the other and then the data were selected, separated and sorted by coding them inductively line-by-line (initial coding) using comparative methods. Then, we focused for frequently initial codes or codes with a high significance and searched for relationships between the initial codes, connected them and built up categories (selective coding).

Analysis of the integration of quantitative and qualitative data

The results of the quantitative and qualitative studies were integrated in an interactive synthesis by comparing them and focusing on the similarities. The synthesis was performed by oscillating the inductive and deductive data and generating the results in an abductive manner (36,37). The results were then visualized in a joint display (52-54) based on the four stages of the pillar integration process: listing, matching, checking, and pillar building, which promotes the abduction process (55). First, raw coded or grouped data are listed (listing). Next, the data are matched with the opposite side and the system searches for parallels, similarities, or other relationships (matching). Subsequently, the data quality must be checked for completeness and correctness (checking). At the final stage, the findings are compared and contrasted; then, they are conceptualized to analyze the themes in a cross-analysis manner with abduction to generate a central phenomenon that answers the research questions. Conclusions are drawn about patterns, insights, or issues that emerged and possible explanations (pillar building).

Ethical approval

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (as revised in 2013). The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Greater Region of Eastern Switzerland (EKOS 17/083).

The ethical approach for the present survey is based on the principles of the “Declaration of Helsinki” and “informed consent”. Anonymity and respect for human dignity is guaranteed at all times during the research process. Drawing any conclusions about the respondents will not be possible at any time. After a brief introduction about the necessity and the aim of this study, the participants got informed about their safety and anonymity and reasons where named why they should answer this questionnaire. Participation was voluntary and could be discontinued at any time. All participants included in this research have given written informed consent to participate in the study.

Results

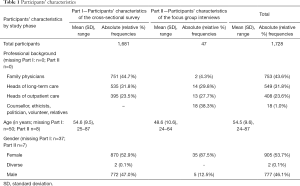

A total of 1,728 participants were included in the survey (n=1,681) and focus group interviews (n=47). Participants’ demographics are shown in Table 1.

Full table

The results of both lines of research are presented in the outer columns (Table 2) and are described and discussed elsewhere (11,12,56). The results form the basis of the data integration, which is presented in the following.

Full table

Data integration involved the social-institution level, the professional-individual level, and the family level. Overall, it was striking that the survey statements and the interview statements were consistent or complemented each other. The quantitative data and the qualitative codes underlying the pillar building themes are shown in the joint display (Table 2).

VSED at social and institutional levels

VSED penetrates the consciousness of Swiss society and influences the health care system (theme 1). Of all deaths in Switzerland, between 0.5% and 0.7% are attributable to VSED. It is therefore a rare phenomenon whose presence has already assumed a very wide range. This was confirmed in the interviews, and compels a closer look at the issue. “VSED does not occur so extremely often now. That maybe before having a case, one should deal with the topic” (FG 2_105). Society is showing an increasing willingness to discuss taboo subjects, such as dying and death, and seeking advice on them. It is therefore not surprising that the interested Swiss population, where assisted suicide is already possible, openly discusses VSED as well. This is reflected in the finding that about one in two health professionals currently considers VSED to be of great relevance in their daily work; this proportion is expected to increase in the future. In sum, the VSED option is already firmly anchored in the population, even before the health care institutions have actively addressed the issue.

There is a chance to anchor VSED in the institution, as it does not contradict its culture (theme 2). Nearly every health care professional stated that VSED does not contradict the culture of their institutions. However, on closer inspection, it is obvious that the institutions have not yet taken a position on the issue. As long as this does not change, VSED will remain in the grey zone and it remains uncertain whether accompaniment will be systematized and professionally implemented.

VSED on professional-individual levels

Ambivalent classifications are an expression of uncertainty in dealing with the topic (theme 3). Most participants characterized VSED as natural because of the slow and familiar dying process. Much less often it was viewed objectively and classified as suicide because of the deliberately induced death. Some vehemently objected to classifying VSED as suicide, because VSED is more a process and not an impulsive act. Above all, it was emphasized that the possibility of breaking off VSED and eating again makes VSED an undescribed form of dying.

More knowledge is required to develop a common understanding of VSED (theme 4). The great difference in classification was also reflected in the unequal level of knowledge about VSED among the participants. Just under half felt familiar with the topic. The rest had no knowledge or felt their knowledge was insufficient. There was criticism that nothing is currently being done to increase the existing knowledge.

Both the pronounced VSED of a person capable of judgement and the unspoken food refusal of a person who is not capable of judgement are anchored in the Swiss health care system and are equally tolerated (theme 5). In the opinion of most participants, VSED decisions are bound to the judgement of the person who is willing to die. It is an act that cannot be carried out without this ability to rationally make decisions. It is therefore astonishing that almost a quarter of the respondents did not consider that determining a person’s ability to judge was important. It was described as relying on one’s gut feeling and the person’s gestures. This discrepancy illustrates the current arbitrary treatment of people who stop eating or refuse to eat, regardless of the underlying reasons.

VSED is only compatible with the moral and ethical attitudes of health professionals at first glance (theme 6). Behind the superficial compatibility between VSED and moral and ethical attitudes lies a lack of alternatives to deal with the situation. VSED is considered more justifiable than, for example, jumping in front of a train. The good about VSED is therefore a better compared to a suicidal act and not actually good in the true meaning of the word. A general ethical and moral stance cannot be taken at all, because the “situation of a young person who is not sick is quite different from when someone has cancer and certain diagnoses” (FG 3_23).

Recommendations on VSED are made with restraint; information is gladly passed on (theme 7). Approximately one in two health professionals could imagine recommending VSED, provided the person willing to die requests it or a terminally ill person expresses the wish to die several times.

More important than individual willingness to accompany a person during VSED is the joint decision within the healthcare team (theme 8). The wish to die through VSED was generally accepted and respected by the participants, provided that the person willing to die is capable of judgment and has an incurable disease. In this case, most participants were willing to accompany the person on this path. However, more important than individual acceptance was the team willingness to collaborate. Every team member’s decision must be respected in the same way the person’s decision to die is respected: “The freedom of the individual stops where it restricts others” (FG 3_24). Creative possibilities can be considered; for example, a health professional is assigned to another department for the period of VSED accompaniment.

Complex professional support without financial coverage (theme 9). Deciding whether to accompany a person on the VSED path and the accompaniment itself represent a challenge. Above all, good interdisciplinary cooperation is of crucial importance and must be coordinated. Especially important are discussions within the team, with the person wishing to die, and with their relatives. These require a lot of time, which poses a problem, because no financing is provided for the accompaniment—VSED is not listed in the Swiss diagnosis-related groups (DRG) used to fund care. In addition to these organizational challenges, health professionals also face burdensome situations regarding direct contact with the person willing to die. First, they must support the person on their path while not pushing them to give up food; second, they must offer the option of stopping VSED, without making it a demand. The occurrence of delirium is described as particularly challenging when the person in a state of disorientation craves to eat and drink. The expressed desire directly contradicts the previously made agreements, which are to be taken over by the professionals in case of disorientation. This places professionals in a dilemma that raises moral concerns.

VSED at the family level

Professionals help relatives to understand the decision of the person willing to die through VSED (theme 10). It is generally difficult to accept the death of a loved one. Therefore, special sensitivity is needed to inform relatives when a person, although still able to live, prefers to die. If relatives cannot accept a loved one’s VSED decision, health professionals often serve as bridge builders to the relatives. They communicate the needs of the person willing to die and provide comprehensive information on the VSED course. The earlier and more intensively relatives are involved in the decision, the more likely they are to support it.

Doing nothing makes it difficult for relatives to accompany a loved one during VSED (Theme 11). Once the relatives have agreed to accompany the loved one, they are considered vulnerable and require intensive support from health professionals. The duration of the dying process, which lasts an average of 14 days, is perceived as lengthy and burdensome, but also as positive, because it allows loved ones to say goodbye. It is also burdensome because relatives are left without a task. “So, drinking and eating has something to do with love. You can’t do that anymore and then you need an alternative” (FG 2_28). The relatives feel helpless by “only being allowed to observe. Just being present, holding hands, having conversations. This is actually what overwhelms many” (FG 2_29). Relatives need assistance during this time, to show them the importance of their presence and to offer alternatives such as a foot massage or reading a story aloud.

The key message of data integration is that Swiss society has managed to anchor its interest in the VSED option in the healthcare system. While no actual positioning is yet taking place within the institutions, health professionals are directly confronted with it. In principle, they are open to VSED, but with some ambivalence, and they would like to have more knowledge so that they can provide professional support to those affected.

Discussion

In this large, mixed-methods study, we investigated existing VSED knowledge and how the topic is currently being dealt with based on participant experiences. The analyses showed that VSED must be viewed from three levels: the social-institutional, the professional-individual, and the family levels.

The results from the social-institutional level clearly show that VSED is an important issue for the Swiss population, which is consistent with the results of Schmid et al. (57), who found that the Swiss show a remarkably high interest in end-of-life decisions. The consequences become apparent when health professionals are confronted by patients’ desire to die through VSED, which is not common but already happens (11,12). Currently, health care professionals do not receive any guidance from their institutions on whether and how to respond to these death wishes. Nor is there any practical recommendation by which to orientate oneself, as is the case in the Netherlands (20). As a result, health professionals are on their own when asked by a patient to accompany him or her during VSED.

Most health professionals classify VSED as a natural dying process, but some equate it with suicide. These attitudes are strongly linked to the individual’s reasons for wanting to die. While there is a high willingness by Swiss physicians to assist patients with unbearable pain, physicians feel very uncomfortable when there is no physical suffering (58), which is very often the case with VSED (1,9,29,59). This highlights the challenging decisions health professionals are confronted with. Insufficient knowledge about VSED makes it more difficult for health professionals to decide how to respond.

If health professionals decide to accompany the patient, it becomes clear once again how little support is provided by the institution. The very complex care required for both the patients and their relatives, and the intensive interdisciplinary cooperation cannot be reflected in the current billing systems; therefore, work is not fully remunerated. As a result, accompanying a person during VSED is arbitrary, and the reasons that one may or may not receive support from health professionals are completely incomprehensible to patients and their families.

At the family level, it is the desire to die rather than VSED itself that leads to irritation and rejection. Wiegand (60) showed that even if relatives understand and accept the wish to die, they are afraid of the dying process and do not feel prepared for it. Heller and Wegleitner (61) asserted that, in today’s society, dying is being forgotten, since it no longer takes place at home, but in institutions. Gamondi et al. (62) pointed out that relatives are often left out of the decision-making process at an early stage; in Switzerland they are mainly responsible for accompanying their loved ones. This was confirmed by our results.

While each level has its own major barriers, it is not yet possible to model exactly how challenges, which involve a combination of all levels and the interaction of all actors, can be dealt with. Future research needs to explore the different relationships of all actors at all levels.

This study’s strength is the integration of quantitative and qualitative data, which made it possible to gain deeper insight into the attitudes of people involved in VSED. However, the study also has limitations. While the quantitative results represent participants from all over Switzerland, the qualitative results are limited to the German-speaking regions. Although these regions proportionally make up the largest share of Switzerland, the group analyses (63) showed that different attitudes were registered in the Lake Geneva region in particular, which could not be fully reflected in the present mixed-methods study. A qualitative survey in the French and Italian-speaking regions is recommended for future research.

Conclusions

The study results show that it is necessary to discuss the VSED issue at several levels. Given the increasing social interest, institutions should position themselves regarding accompaniment and incorporate guidelines for all employees. In addition, employees require training to provide adequate support to all the persons involved. Furthermore, the extensive services required of health professionals accompanying VSED must be remunerated. A clear VSED policy and well-trained staff will help relatives and patients with their decision and assist them through the patient’s dying process.

Acknowledgments

The greatest thanks go to the participants of both studies who were willing to share their valuable impressions with us. We would like to take this opportunity to express our sincere thanks to the professional organizations Associations Spitex privée Suisse, CURACASA, CURAVIVA, and Médecins de famille et de l’efance Suisse, who facilitated our access to the quantitative survey and to the organization Palliative Zug, who supported us in the organization of the focus groups. Special thanks go to Prof. Dr. Wilfried Schnepp (†), who helped this study to become what it is today with his constructive suggestions.

Funding: The quantitative study and the mixed methods study were sponsored by “Research in Palliative Care” of the Swiss Academy of Medical Sciences, supported by Stanley Thomas Johnson Foundation and the Gottfried and Julia Bangerter-Rhyner-Foundation. The qualitative study was supported by the Ebnet-Foundation and the Foundation Palliacura.

Footnote

Reporting Checklist: The authors have completed the MDAR reporting checklist. Available at http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/apm-20-1339

Data Sharing Statement: Available at http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/apm-20-1339

Conflicts of Interest: Both authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/apm-20-1339). SS reports grants from Swiss Academy of Medical Sciences, grants from Ebnet-Foundation, grants from Forundation Palliacura, during the conduct of the study. AF reports grants from Swiss Academy of Medical Sciences, grants from Ebnet-Foundation, grants from Forundation Palliacura, during the conduct of the study.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (as revised in 2013). The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Greater Region of Eastern Switzerland (EKOS 17/083) and informed consent was taken from all participants.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- Bolt EE, Hagens M, Willems D, et al. Primary care patients hastening death by voluntarily stopping eating and drinking. Ann Fam Med 2015;13:421-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Feichtner A, Weixler D, Birklbauer A. Voluntary stopping eating and drinking (VSED): a position paper of the Austrian Palliative Society. Wien Med Wochenschr 2018;168:168-76. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hoekstra NL, Strack M, Simon A. Physicians attitudes on voluntary refusal of food and fluids to hasten death - results of an empirical study among 255 physicians. Z Palliativmed 2015;16:68-73.

- Lowers J, Hughes S, Preston NJ. Overview of voluntarily stopping eating and drinking to hasten death. Ann Palliat Med 2020;9:40. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Mattiasson AC, Andersson L. Staff attitude and experience in dealing with rational nursing home patients who refuse to eat and drink. J Adv Nurs 1994;20:822-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Pope TM. Voluntarily stopping eating and drinking. Narrat Inq Bioeth 2016;6:75-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Requena P. Andrade Dos Santos AdP. Hastening death by voluntary stopping of eating and drinking. A new mode of assisted suicide? Cuad Bioet 2018;29:257-68. [PubMed]

- Shinjo T, Morita T, Kiuchi D, et al. Japanese physicians’ experiences of terminally ill patients voluntarily stopping eating and drinking: a national survey. BMJ Support Palliat Care 2019;9:143-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Chabot BE, Goedhart A. A survey of self-directed dying attended by proxies in the Dutch population. Soc Sci Med 2009;68:1745-51. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Onwuteaka-Philipsen BD, Brinkman-Stoppelenburg A, Penning C, et al. Trends in end-of-life practices before and after the enactment of the euthanasia law in the Netherlands from 1990 to 2010: A repeated cross-sectional survey. Lancet 2012;380:908-15. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Stängle S, Schnepp W, Büche D, et al. Family physicians’ perspective on voluntary stopping of eating and drinking: a cross-sectional study. J Int Med Res 2020;48:300060520936069. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Stängle S, Schnepp W, Büche D, et al. Long-term care nurses’ attitudes and the incidence of voluntary stopping of eating and drinking: a cross-sectional study. J Adv Nurs 2020;76:526-34. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ivanović N, Büche D, Fringer A. Voluntary stopping of eating and drinking at the end of life - a ‘systematic search and review’ giving insight into an option of hastening death in capacitated adults at the end of life. BMC Palliat Care 2014;13:1-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Stängle S, Schnepp W, Fringer A. The need to distinguish between different forms of oral nutrition refusal and different forms of voluntary stopping of eating and drinking. Palliat Care Soc Pract 2019;13:1178224219875738. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bernat JL, Gert B, Mogielnicki RP. Patient refusal of hydration and nutrition. An alternative to physician-assisted suicide or voluntary active euthanasia. Arch Intern Med 1993;153:2723-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Quill TE, Byock IR. Responding to intractable terminal suffering: the role of terminal sedation and voluntary refusal of food and fluids. Ann Intern Med 2000;132:408-14. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Swiss Academy of Medical Sciences. Management of dying and death2018 6 August 2019:[32 p.]. Available online: https://www.samw.ch/en/Ethics/Ethics-in-end-of-life-care/Guidelines-management-dying-death.html

- Berry EM, Marcus EL. Disorders of eating in the elderly. J Adult Dev 2000;7:87-99. [Crossref]

- Radbruch L, Münch U, Maier BO, et al. Positionspapier der Deutschen Gesellschaft für Palliativmedizin zum freiwilligen Verzicht auf Essen und Trinken2019 June 18, 2020; 1:[1-15 pp.]. Available online: https://www.dgpalliativmedizin.de/phocadownload/stellungnahmen/DGP_Positionspapier_Freiwilliger_Verzicht_auf_Essen_und_Trinken%20.pdf

- Royal Dutch Medical Association, Dutch Nurses’ Association Caring for people who consciously choose not to eat and drink so as to hasten the end of life2014 June 11, 2020:[51 p.]. Available online: https://www.knmg.nl/advies-richtlijnen/knmg-publicaties/publications-in-english.htm

- Christenson J. An ethical discussion on voluntarily stopping eating and drinking by proxy decision maker or by advance directive. J Hosp Palliat Nurs 2019;21:188-92. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Chuang E, Flicker LS. When voluntary stopping of eating and drinking in advanced dementia is no longer voluntary. Hastings Center Report 2018;48:24-5. [Crossref]

- Marks AD, Ahronheim JC. Advance directive as Ulysses contract: the application of stopping of eating and drinking by advance directive. Am J Hosp Palliat Care 2020;37:974-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Menzel PT. Voluntarily stopping eating and drinking: a normative comparison with refusing lifesaving treatment and advance directives. The Journal of Law, Medicine & Ethics 2017;45:634-46. [Crossref]

- Pope TM. Whether, when, and how to honor advance VSED requests for end-stage dementia patients. Am J Bioeth 2019;19:90-2. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Trowse P. Voluntary stopping of eating and drinking in advance directives for adults with late-stage dementia. Australas J Ageing 2020;39:142-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wright JL, Jaggard PM, Holahan T, et al. Stopping eating and drinking by advance directives (SED by AD) in assisted living and nursing homes. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2019;20:1362-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Swiss Academy of Medical Sciences. Care and treatment of people with dementia2018 23 March 2020:[32 p.]. Available online: https://www.samw.ch/en/Publications/Medical-ethical-Guidelines.html

- Stängle S, Schnepp W, Büche D, et al. Pflegewissenschaftliche Erkenntnisse über die Betroffenen, den Verlauf und der Begleitung beim freiwilligen Verzicht auf Nahrung und Flüssigkeit aus einer standardisierten schweizerischen Gesundheitsbefragung. ZfmE 2019;65:237-48.

- Pope TM, West A. Legal briefing: voluntary stopping of eating and drinking. J Clin Ethics 2014;25:68-80. [PubMed]

- Quill TE, Ganzini L, Truog RD, et al. Voluntarily stopping eating and drinking among patients with serious advanced illness - clinical, ethical, and legal aspects. JAMA Intern Med 2018;178:123-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ganzini L, Goy ER, Miller LL, et al. Nurses’ experiences with hospice patients who refuse food and fluids to hasten death. N Engl J Med 2003;349:359-65. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Saladin N, Schnepp W, Fringer A. Voluntary stopping of eating and drinking (VSED) as an unknown challenge in a long-term care institution: An embedded single case study. BMC Nurs 2018;17:39. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Stängle S, Schnepp W, Mezger M, et al. Voluntary stopping of eating and drinking in Switzerland from different points of view: protocol for a mixed-methods study. JMIR Res Protoc 2018;7:e10358. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Johnson RB, Onwuegbuzie AJ. Mixed methods research: a research paradigm whose time has come. Educational Researcher 2004;33:14-26. [Crossref]

- Hintikka J. What is abduction? The fundamental problem of contemporary epistemology. In: Hintikka J. editor. Inquiry as Inquiry: A Logic of Scientific Discovery. 5. Dordrecht: Springer, 1999:91-113.

- Hobbs JR, Stickel ME, Appelt DE, et al. Interpretation as abduction. Artif Intell 1993;63:69-142. [Crossref]

- Creswell JW. Basic and Advanced Mixed Methods Designs. In: Creswell JW, editor. A Concise Introduction to Mixed Methods Research. London: Sage Pubn, 2014:34-50.

- Morgan DL. Pragmatism as a paradigm for social research. Qual Inq 2014;20:1045-53. [Crossref]

- Creswell JW, Plano Clark VL. Designing and conducting mixed methods research. London: Sage Publications Ltd., 2018:492.

- Polit DF, Beck CT, editors. Essentials of nursing research - appraising evidence for nursing practice. Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer Health, 2018.

- Newman I, Ridenour CS, Newman C, et al. A typology of research purposes and its relationship to mixed methods. In: Tashakkori A, Teddlie C. editors. Handbook of mixed methods in social and behavioral research. Thousand Oaks, Ca: Sage, 2003:167-88.

- Colton D, Covert RW. Designing and constructing instruments for social research and evaluation. 1 ed. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass, 2007:394.

- Polit DF, Beck CT, Owen SV. Is the CVI an acceptable indicator of content validity? Appraisal and recommendations. Res Nurs Health 2007;30:459-67. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Polit DF, Beck CT. The content validity index: Are you sure you know what’s being reported? critique and recommendations. Res Nurs Health 2006;29:489-97. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Acquadro C, Conway K, Giroudet C, et al. Linguistic validation manual for health outcome assessments. Lyon: Mapi Institute, 2012:152.

- Stängle S, Schnepp W, Mezger M, et al. Development of a questionnaire to determine incidence and attitudes to “voluntary stopping of eating and drinking”. SAGE Open Nurs 2019;5:237796081881235. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Charmaz K. Constructing grounded theory: a practical guide through qualitative analysis. London: SAGE Publications Ltd, 2006.

- Glaser BG. The Constant Comparative Method of Qualitative Analysis. Social Problems 1965;12:436-45. [Crossref]

- Carlsen B, Glenton C. What about N? A methodological study of sample-size reporting in focus group studies. BMC Med Res Methodol 2011;11:26. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Krueger RA, Casey MA. Focus groups: a practical guide for applied research. Thousand Oaks, California: SAGE Publications, 2009.

- Bazeley P. Editorial: integrating data analyses in mixed methods research. Journal of Mixed Methods Research 2009;3:203-7. [Crossref]

- Fetters MD, Freshwater D. The 1 + 1 = 3 integration challenge. Journal of Mixed Methods Research 2015;9:115-7. [Crossref]

- Guetterman TC, Fetters MD, Creswell JW. Integrating quantitative and qualitative results in health science mixed methods research through joint displays. Ann Fam Med 2015;13:554-61. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Johnson RE, Grove AL, Clarke A. Pillar integration process: a joint display technique to integrate data in mixed methods research. Journal of Mixed Methods Research 2017;13:301-20. [Crossref]

- Stängle S, Schnepp W, Büche D, et al. Survey about voluntary stopping of eating and drinking in Swiss outpatient care. GeroPsych 2021. In Press. [Crossref]

- Schmid M, Zellweger U, Bosshard G, et al. Medical end-of-life decisions in Switzerland 2001 and 2013: Who is involved and how does the decision-making capacity of the patient impact? Swiss Med Wkly 2016;146:w14307. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Fischer S, Huber CA, Furter M, et al. Reasons why people in Switzerland seek assisted suicide: the view of patients and physicians. Swiss Med Wkly 2009;139:333-8. [PubMed]

- van der Heide A, Brinkman-Stoppelenburg A, van Delden H, et al. Sterfgevallenonderzoek 2010: euthanasie en andere medische beslissingen rond het levenseinde 2012 June 18, 2020: [70 p.]. Available online: https://publicaties.zonmw.nl/sterfgevallenonderzoek-2010-euthanasie-en-andere-medische-beslissingen-rond-het-levenseinde/

- Wiegand DL. Family experiences during the dying process after withdrawal of life-sustaining therapy. Dimens Crit Care Nurs 2016;35:160-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Heller A, Wegleitner K. Dying and death in societal transformation. Bundesgesundheitsblatt Gesundheitsforschung Gesundheitsschutz 2017;60:11-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gamondi C, Pott M, Preston N, et al. Family caregivers’ reflections on experiences of assisted suicide in Switzerland: a qualitative interview study. J Pain Symptom Manage 2018;55:1085-94. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Stängle S, Büche D, Häuptle C, et al. Experiences, personal attitudes and professional stances of Swiss health care professionals about voluntary stopping of eating and drinking to hasten death: a cross-sectional study. J Pain Symptom Manage 2020;S0885-3924(20)30644-8.