Early integration of palliative care for outpatients with advanced cancer in general practice: how is the situation?—a cohort study

Introduction

People with advanced cancer receive specialist oncologic care in highly specialised, certified centres and practices, but almost all cancer patients visit their general practitioners (GP) too. Approximately one third (34.5%) of these discuss decisions concerning diagnostics and therapy with their GP. Patients want their GP to take an active part in their cancer therapy (1). The GP in Germany has, for example, the possibility of referring patients to a specialist palliative care team for full palliative care, but also for an initial consultation, at any time in the course of the disease. What remains unclear however, is at what point physicians actually take advantage of this, early on, e.g., at the time of diagnosis, or later, only once the patient shows signs of serious illness.

In April 2007, specialist outpatient palliative care (SOPC) was introduced by law into the German health care system for every patient covered by public health insurance, entitling every health insured person in Germany to said treatment, should they need it. The aim of the new article in Section 37b, Volume V of the German Social Legal Code (SGB V) was to establish extended palliative care and to improve outpatient palliative care at the end of life. SOPC is provided by multi-professional teams for patients suffering from complex symptoms and complaints associated with severe and advanced disease.

For many people, palliative care is associated with treatment in the terminal stage of cancer. It is often delayed until the last weeks or days of life (2). In the German guideline for palliative care from 2014, it is recommended that every patient with cancer receive information about palliative care, independently of the stage of disease or concurrent oncologic therapy (3). Compared with standard cancer care alone, early palliative care significantly improves health-related quality of life (4). Since the innovative 2010 study by Temel, we know that, with respect to quality of life—especially anxiety and psychological wellbeing—as well as survival time, these patients benefit from the early integration of palliative care providers into their multidisciplinary cancer treatment team. In this study patients were seen by the palliative specialist within 8 weeks (5). Patients with cancer may suffer from physical and emotional symptoms, existential and social distress and have a short survival time. There are strong clinical data supporting the feasibility and usefulness of early integration of palliative care in cancer treatment to provide better quality of life, symptom control and survival. The question is not if, but when, from whom and how palliative care should best be integrated into modern cancer therapy. Hui found several indicators related to structures, education, research and administration (6). In Brazil, de Oliveira Valentino found that most patients first received palliative care consultation shortly before death and that the numbers of patients receiving consultation at a late stage of their disease increased throughout the study (7). Bruera already postulated in 2012 that early access to palliative care would improve symptom control and quality of life and reduce the cost of care (8). Hui showed six recurrent themes pertaining to outpatient cancer palliative care referrals (physical symptoms, cancer diagnosis, prognosis, performance status, psychosocial distress, end of life care planning) (9). Further studies showed the improvement of almost all symptoms evaluated (10,11). The updated clinical practice guideline of the American Society of Clinical Oncology from 2017 recommends that inpatients and outpatients with advanced cancer receive dedicated palliative care services early in the course of their disease, concurrent with active treatment (12).There is certainly room for improvement in the care of cancer patients and studies of the early integration of palliative care reveal deficits in oncological practice (13). Palliative care is warranted from the time of diagnosis of incurable cancer. At this early stage, palliative care consists of generalist palliative care provided by oncologists and general practitioners with additional support from a specialist palliative care team (14).

With these recommendations in mind, we wanted to know to what extent GPs refer patients to palliative care specialists. Furthermore, we wanted to know how often this referral is made early on, within the first week post diagnosis, for outpatients with advanced, incurable cancer. We therefore studied the referrals from GPs to SOPCs during the years 2015–2016 for patients with advanced cancer.

We present the following article in accordance with the STROBE reporting checklist (available at http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/apm-20-2377).

Methods

We studied claims data from a German statutory health insurance company (“AOK”, Allgemeine Ortskrankenkasse) in the federal state of Baden-Wuerttemberg. The AOK is the biggest German health insurance company with more than 19 million insured throughout Germany as of 2015. The members of the AOK are representative of the German population as a whole, especially with respect to range of disease. A full census of 3.87 million insured in Baden-Wuerttemberg was available for this study. The observation time was the 2-year period from 01-Jan-2015 until 31-Dec-2016.

The included data were derived from a comprehensive evaluation programme in German primary care, the Hausarztzentrierte Versorgung (HZV), loosely translated as “family doctor coordinated care”. The HZV is a programme which encourages patients to voluntarily enroll themselves with a family doctor pursuant to Section 73b, Volume V of the German Social Legal Code. The programme requires that they commit to consulting their general practitioner before being seen by a specialist, thereby reducing some the strain posed by specialist consultations on the healthcare system while supporting a wholistic approach to primary care. Data were made available to the Department of General Practice and Health Services Research, University Hospital Heidelberg, Germany, in order to assess the effectiveness of the HZV programme. The AOK granted additional permission for the data analysis carried out within this study.

With these data, we could identify patients with advanced metastatic cancer using corresponding ICD-10 (International Classification of Diseases, Injuries, and Causes of Death, 10th revision) codes.

We used the WHO definition of palliative care from 2002. Palliative care is an approach that improves the quality of life of patients and their families facing the problems associated with life-threatening illness. For many chronic diseases, there are no sharp thresholds between chronic disease and palliative care. Patients with metastatic cancer fulfill the WHO-definition unequivocally.

Patients receiving palliative care were identified by specific codes of the German medical fee schedule (“EBM”, Einheitlicher Bewertungsmassstab). Moreover, we could obtain precise information on when general practitioners made a referral to a SOPC team with EBM codes 01425 (referral to palliative care specialist) or 01426 (repeated referral to palliative care specialist) and the corresponding timestamp.

Above all, we wanted to show the distribution of the time interval between the labelling of a patient as “palliative” and the eventual referral to a SOPC team. Therefore, the analysis methods were descriptive only.

For the purposes of this study, referrals to specialist palliative care are understood to fulfil the criteria for “early integration” when they are made within the first four weeks post diagnosis.

Data storage, management and extraction was performed with MySQL Community Server x64 (Oracle Corporation, Redwood Shores, CA, USA). In order to calculate frequencies, rates and percentages we used SAS PROC SQL (SAS 9.4 x64, SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

Ethical approval for the study was given by the University Hospital Heidelberg Ethics Committee (No. S-359/2013).

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (as revised in 2013). Informed consent was not applicable.

Results

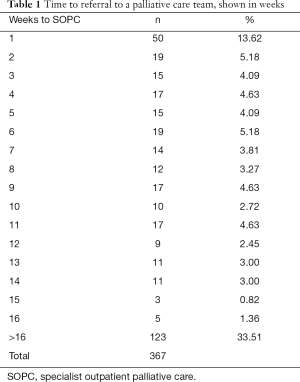

In 2015, we found 3,872,245 people insured by the health insurance company (AOK Baden-Wuerttemberg). This corresponded roughly to 5% of the German population: 82.2 Mio people in 2015 (15). By their GP 48,091 (1.24%) patients had been labeled had been labelled “palliative care necessary” or “palliative patient” and 3,535 of these palliative patients had advanced metastatic cancer. Treated by their GP were 2,866 (81.1%) palliative cancer patients. 669 (18.9%) were additionally referred to a SOPC team. Of these 669 patients, 302 (45.1%) were referred to a palliative care team on the same day that they were designated as palliative and 367 (54.9%) received their referral later. Only 101 (15.1%) patients had a referral 4 weeks after the diagnosis was made, 161 (24.1%) after 8 weeks, 214 (31.9%) after 12 weeks, 244 (66.5%) after 16 weeks and 123 (33.5%) did not receive a referral within 16 weeks (Figures 1,2, Table 1). With respect to all outpatients with advanced cancer and metastases, 463 (16.2%) patients cared for by their GP fulfilled the criteria for early integration of palliative care for patients with advanced cancer.

Full table

Discussion

The WHO defines palliative care as an “approach that improves the quality-of-life of patients and their families facing the problems associated with life-threatening illness, through the prevention and relief of suffering by means of an early identification and impeccable assessment and treatment of pain and other problems, physical, psychosocial and spiritual.” As further affirmed by the WHO, palliative care is applicable early in the course of any illness in conjunction with life-prolonging therapies (16). The American Society of Clinical Oncology similarly recommends integrating palliative care early in the course of illness for patients with cancer (17). In the striking study of Temel et al. (5), early integration means a referral to palliative care specialists within 8 weeks after the diagnosis was made. As shown here, these recommendations have not been widely implemented in German general practices for outpatients, much to their disadvantage.

According to our study, only 16.2% of all outpatients with advanced metastatic cancer were referred early, e.g., within 8 weeks, in the course of their disease to a specialist palliative care team by their GP, either for support or for advice. An additional 1.8% of the patients received a delayed referral to a palliative specialist, with delays reaching until 16 weeks, and 4.3% more than 16 weeks after. Exactly 76.6% of all patients with advanced metastatic cancer had no referral from the GP to a palliative care provider, even though it is known that the early integration of palliative care into the treatment of metastatic cancer leads to significant improvements in both quality of life and mental health. As compared to patients receiving standard care, patients receiving early palliative care have longer survival but less aggressively interventional care at the end of life. Therefore, it is very important to emphasize that GPs should reconsider their palliative care consultation strategy, especially regarding patients with metastatic cancer. By our analysis, only about a quarter of these patients received such a referral.

Full integration of oncologic and palliative care relies on the specific knowledge and skills of two modes of care: the tumour-directed approach, for which the focus is on combatting the disease, and the host-directed approach, which focuses on the patient with the disease. The early delivery of host-directed care by specialist palliative care teams alongside tumour-directed treatments promotes patient-centred care. Systematic assessment and use of patient reported outcomes, especially when patients are encouraged to take an active role in the planning and execution of their treatment, improves physical and mental health and the efficient use of health-care resources (18).

Hui and Bruera discussed various strategies to integrate palliative care and oncology by optimizing clinical infrastructure (8,9). They emphasize that outpatient access to palliative care is important and that the multidimensional needs of oncologic patients have to be addressed. Unfortunately, there remains uncertainty as to who should be referred for early palliative care.

Oncologists occupy an important role in delivering primary palliative care. But the role of general practitioners seems to remain undefined (19), despite the fact that many patients stay in contact with their GP during their oncologic treatment. Quill emphasised that basic symptom management should constitute a routine aspect of care delivered by any practitioner, whereas the more complex skills required by specialist palliative care providers could be acquired through a 12-month specialty training programme. And while this specialist care may seem, or even be, optimal for patients, it remains clear that there are nowhere near enough palliative care specialists to provide all palliative care services for everyone with terminal illness (20). A more efficient approach would be to give all patients with advanced cancer the possibility of receiving early consultations by specialists in palliative care with recommendations being given to the primary care provider, thereby conserving scarce resources. The role of general practitioners could therefore be strengthened while the challenges they face due to the intensity and medical complexity of palliative care could be ameliorated through a system of early referral and intensive cooperation between colleagues (21). The result could be a significant improvement in treatment and outcomes for patients with advanced cancer.

The strength of this study lies in its access to a large study sample from a large region in Germany. This study was limited by the fact that only a small part of patients received a referral to palliative care teams by their GP and only a portion of these were referred very early. Furthermore, we have no data on whether patients received a referral to a palliative care specialist from their oncologists. Also unclear was whether the patients had seen a palliative care specialist already in the hospital. But even considering these possibilities, we think that an early contact with the SOPC in their home environment presents an important chance to provide better care for patients and their relatives. And we believe that, for patients in Germany, the general practitioner should consider an early referral to a palliative specialist, even if only to establish contact with the team. A further limitation was that we could not find information from the database about the quality of care and the follow up of the patients.

Conclusions

Most outpatients with advanced cancer in general practice get no specialist palliative care. A small portion of them get it very late. It seems to be important that all colleagues realize that palliative care means much more than end-of-life care during the last few days, or at most weeks, of the patients’ lives. General practitioners are encouraged to identify palliative patients with metastatic cancer early and should refer those patients with advanced disease to a palliative care team to provide palliative care advice in addition to standard care for better quality of life and longer survivability for the patients.

Acknowledgments

The data usage grant from the AOK Baden-Württemberg for this study is greatly acknowledged.

Funding: None.

Footnote

Reporting Checklist: The authors have completed the STROBE reporting checklist. Available at http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/apm-20-2377

Data Sharing Statement: Available at http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/apm-20-2377

Peer Review File: Available at http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/apm-20-2377

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/apm-20-2377). The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (as revised in 2013). Ethical approval for the study was given by the University Hospital Heidelberg Ethics Committee (No. S-359/2013). Informed consent was not applicable.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- Lang V, Walter S, Fessler J, et al. The role of the general practitioner in cancer care: a survey of the patient’s perspective. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol 2017;143:895-904. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Murray SA, Kendall M, Mitchel G, et al. Palliative care from diagnosis to death. BMJ 2017;356:j878. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Palliativmedizin für Patienten mit einer nicht heilbaren Krebserkrankung, German Guideline for palliative care, Version 1.0, AWMF-Register: 128/001 OL. 2015:175-7.

- Haun MW, Estel S, Rücker G, et al. Early palliative care for adults with advanced cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2017;6:CD011129 [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Temel JS, Greer JA, Muzikansky A, et al. Early Palliative Care for Patients with metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med 2010;363:733-42. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hui D, Kim YJ, Park JC, et al. Integration of oncology and palliative care: A systematic review. Oncologist 2015;20:77-83. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- de Oliveira Valentino TC, Ribeiro Palva BS, de Oliveira MA, et al. Factors associated with palliative care referral among patients with advanced cancers: a retrospective analysis of a large Brazilian cohort. Support Care Cancer 2018;26:1933-41. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bruera E, Yennurajaligam S. Palliative care in advanced cancer patients: How and when? Oncologist 2012;17:267-73. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hui D, Meng Y, Bruera S, et al. Referral criteria for outpatient palliative cancer care: A systematic review. Oncologist 2016;21:895-901. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bischoff K, Weinberg V, Rabow MW. Palliative and oncologic co-management: symptom management for outpatients with cancer. Support Care Cancer 2013;21:3031-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Greer JA, Jackson VA, Meier DE, et al. Early integration of palliative care services with standard oncology care for patients with advanced cancer. CA Cancer J Clin 2013;63:349-363. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ferrell BR, Temel JS, Temin S, et al. Integration of palliative care into standard oncology care: American Society of Clinical Oncology Clinical Practice Guideline Update. J Clin Oncol 2017;35:96-112. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Schuler US. Early integration of palliative and oncological care Con Oncol Res Treat 2019;42:19-24. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gaertner J, Weingaertner V, Wolf J, et al. Early palliative care for patients with advanced cancer: how to make it work? Curr Opin Oncol 2013;25:342-52. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Statistisches Bundesamt: Statistisches Jahrbuch Deutschland und Internationales 2017;23

- World Health Organisation. Definition of Palliative Care. World health Organisation Website (www.who.int/cancer/palliative//definition/en/.) Accessed March 03, 2019

- Smith TJ, Temin S, Alesi ER, et al. American Society of Clinical Oncology provisional clinical opinion: the integration of palliative care into standard oncology care. J Clin Oncol 2012;30:880-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kaasa S, Loge JH, Aapro M, et al. Integration of oncology and palliative care: a Lancet Oncology Commission. Lancet Oncol 2018;19:e588-e653. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hui D, Bruera E. Integrating palliative care into the trajectory of cancer car. Nat Rev Clin Oncol 2016;13:159-71. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Quill TE, Abernethy AP. Generalist plus Specialist Palliative Care – Creating a more Sustainable Model. New Engl J Med 2013;368:1173-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Dahlhaus A, Vanneman N, Siebenhofer A, et al. Involvement of general practitioners in palliative care. Support Care Cancer 2013;21:3293-300. [Crossref] [PubMed]