Impact of Tai Chi on CRP, TNF-alpha and IL-6 in inflammation: a systematic review and meta-analysis

Introduction

Coronavirus disease-2019 (COVID-19), known as a novel infectious disease, has caused worldwide spread currently (1-3). When preparing this manuscript, the World Health Organization (WHO) reported over 2.7 million new COVID-19 cases last week (https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/situation-reports). The severity and mortality rates of COVID-19 are higher in elderly patients than young and middle-aged people (4-6). Previous studies have reported that CRP, TNF-alpha, and IL-6 in COVID-19 patients are significantly increased, and their progressive increases are clinical warning indicators of severe and critical severity (7-12). The COVID-19 challenges the national healthcare system for every country, which may overwhelm the available medical resources (13-15).

Tai Chi, known as a form of traditional Chinese health-promoting martial art, is beneficial for preventing and complemental treating of diseases (16-20), and the training intensity is suitable for the elderly (16-22). Besides, Tai Chi has a significant effect on alleviating mental stress and anti-depression (23-25), which is common during the COVID-19 outbreak (26,27). At present, Tai Chi was adopted in the Beijing New Coronavirus Pneumonia Traditional Chinese Medicine Prevention and Treatment Program (http://www.satcm.gov.cn/xinxifabu/gedidongtai/2020-03-08/13717.html) and New Coronary Pneumonia Discharge Rehabilitation Program (http://www.nhc.gov.cn/xcs/zhengcwj/202003/d4558d2cc35e44d5b9adba7c911e0b4c.shtml). Elevated inflammatory markers are one of the main concerns in COVID-19. Tai Chi may have potential benefits in COVID-19 by reducing inflammatory markers level.

Many corresponding randomized controlled trials (RCTs) have found that Tai Chi has a positive regulating effect on inflammatory markers (28-31), while the results are limited and inconclusive due to the small sample size of individual experiments. The purpose of this systematic review is to evaluate the effect of Tai Chi on C reactive protein (CRP), tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-alpha) and interleukin-6 (IL-6).

We present the following article in accordance with the PRISMA reporting checklist (available at https://dx.doi.org/10.21037/apm-21-640).

Methods

Trial registration

The study was prospectively registered in PROSPERO with the number CRD42020177655.

Literature search

Five English (PubMed, Web of Science, Physiotherapy Evidence Database, Cochrane Library and Embase) and Four Chinese electronic databases (CNKI, Wanfang, China Science and Technology Journal Database and SinoMed) were searched from inception to April 1st, 2020. A search strategy in English electronic databases was composed using the Medical Subject Headings terms (MeSH) of ‘tai ji’, ‘C-reactive Protein’, ‘Tumour Necrosis Factor-alpha’, ‘Interleukin-6’, ‘inflam*’ and their free text terms. Moreover, the terms of ‘baixibaojiesu6’, ‘baixibaojiesu-6’, ‘IL-6’, ‘IL6’, ‘zhongliuhuaisiyinziα’, ‘zhongliuhuaisiyinzi-α’, ‘TNF-α’, ‘TNFα’, ‘CRP’, ‘Cfanyingdanbai’, ‘yanzheng’, ‘taiji’ were used to make up search strategy in Chinese electronic databases. No language restrictions were applied to all the databases searching.

Study selection

The following eligibility criteria were applied: (I) participants: human participants; (II) intervention: Tai Chi with or without usual care, health education, drug therapy, psychosocial therapy; (III) comparison: usual care or health education or drug therapy or psychosocial therapy; (IV) outcomes: C-reactive protein, tumour necrosis factor-alpha, interleukin-6; (V) study design: RCTs (length no less than 4 weeks).

Two reviewers (Cheng S. and Cui Q.) searched databases and selected articles independently. If any disagreement emerged between the two reviewers, the third person (Feng S.) participated in discussions and proposed solutions to reach an agreement.

Data extraction and quality assessment

Two reviewers extracted data from selected studies and assessed the methodological quality independently. If any disagreement emerged between the two investigators, the third person participated in discussions and proposed solutions to reach an agreement. Extracted information included study ID, participant characteristics, exercise frequency and time length, intervention measures of the experimental group and the control group, outcomes measured and adverse events. To calculate the effect size, quantitative data (mean, the standard deviation of the outcomes and the number of participants) in each group were extracted by the same investigator.

The revised Physiotherapy Evidence Database (PEDro) scale was used to assess the methodological quality, which is applicable to the assessment of physiotherapy. The original scale includes 11 items (32). Due to the blinded participants and instructors could not be achieved in selected studies, the revised PEDro scale contains the following 9 items: eligibility criteria, allocation randomly, allocation concealment, similar baseline, blinding assessor(s), retention rate of ≥85%, intention-to-treat analysis, between group statistical comparisons, point measures and measures of variability for at least one outcome. One point was awarded when a criterion was clearly satisfied. The higher score indicated better quality.

The authors of the studies which did not present the necessary data in their published papers were contacted by emails.

Statistical analysis

Revman version 5.3 was used to analyze the extracted data. Continuous outcomes were described by standardized mean difference (SMD). I2 test was used to judge the heterogeneity of meta-analysis. I2>50% was considered to have a significant heterogeneity. The random-effect model was adopted for high heterogeneity (I2>50%), and the fixed-effect model for low heterogeneity (I2<50%). Sub-group analysis was used to identify potential factors of high heterogeneity.

To investigate whether there was a dose-response relationship between Tai Chi and outcomes, a subgroup analysis was performed based on the total amount of exercise. Since the included studies did not report the intensity of Tai Chi exercise, considering all selected studies had the same exercise intensity. The exercise amount can be expressed as total exercise time (TET).

Where, TET means total exercise time, ETPD means exercise time per day, DEPW means days of exercise per week and TWE means total weeks of exercise.

P values <0.05 were considered statistically significant. Publication bias was not assessed due to the number of selected studies is less than 10 in each analysis.

Results

Search results

A total of 488 records (including duplicates) were found by searching the nine databases, of which 132 records were retrieved from Chinese electronic databases and 356 records from English. Figure 1 shows the process of study selection. After removing 232 duplicated records, 256 records were assessed according to the titles and abstracts of articles, further excluding 212 irrelevant records. The remaining 44 full-text articles were assessed, 35 of which were excluded, and the reasons are presented in Figure 1. Eventually, 9 studies were selected for this meta-analysis (23,33-40).

Characteristics of included studies

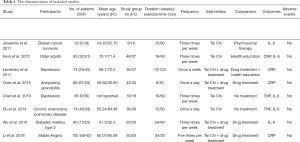

Table 1 shows the characteristics of the included studies. They were published between 2010 and 2019, and among them, 7 diseases were involved in the selected studies. The sample size ranged from 19 to 100 per study. Female percentages ranged from 29.1% to 100%. The mean age of participants ranged from 30 to 71 years, except one article did not mention the mean age (40). The duration of intervention ranged from 8 to 24 weeks. Weekly exercise frequency ranged from one to seven times, and each exercise time ranged from 30 to 120 minutes. Four trials adopted Tai Chi as the intervention group (33,34,38,40) and 5 trials adopted a combined intervention of Tai Chi and drug treatment (23,35-37,39). The comparison group included psychosocial therapy, health education, drug treatment, and no treatment. Of the 9 studies, the outcome of TNF-alpha, IL-6 and CRP were reported in three (36,38,40), six (33-36,38,40), and four (23,33,37,39) articles, respectively. No adverse events occurred during studies.

Full table

Study quality assessment

Table 2 shows the study quality of each included article. Among them, sum scores ranged from 6 to 9, with a median of 7. Only two studies used allocation concealment (23,34), and one study adopted outcome assessment blinding (23). Two studies did not use intention-to-treat analysis (33,34).

Full table

Primary outcomes

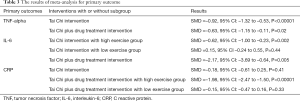

Table 3 presents the results of meta-analysis for primary outcomes. We found that high heterogeneity drops to 0 when using 2,500 min (exercise amount) as the cut-off value. Therefore, we further conducted subgroup analyses according to the exercise amount: low exercise group (exercise amount less than 2,500 min) and high exercise group (exercise amount more than 2,500 min).

Full table

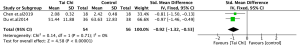

TNF-alpha

A total of 3 studies involving TNF-alpha (36,38,39). Considering the relatively low heterogeneity of the included studies (I2=0%) in the Tai Chi intervention, we adopted a fixed-effect model.

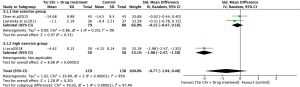

Tai Chi showed a significant benefit on reducing TNF-alpha both in the Tai Chi intervention and the Tai Chi plus drug treatment intervention (SMD =–0.92, 95% CI: –1.32 to –0.53, P<0.00001) (see Figure 2) (SMD =–0.63, 95% CI: –1.15 to –0.11, P=0.02) (see Figure 3).

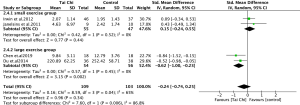

IL-6

A total of 6 studies involving IL-6 (33-36,38,40). The heterogeneity of the included studies was significantly high (I2=65%) in the Tai Chi intervention.

The results show that Tai Chi significantly reduced IL-6 in high exercise group (SMD =–0.62, 95% CI: –1.00 to –0.23, P=0.002) (Figure 4). However, it didn’t have shown the efficacy in low exercise group (SMD =0.15, 95% CI: –0.24 to 0.55, P=0.44) (see Figure 4).

In Tai Chi plus Drug treatment intervention, Tai Chi was associated with decreased IL-6 (SMD =–2.17, 95% CI: –3.69 to –0.64, P=0.005; I2=87%) (see Figure 5).

CRP

A total of 4 studies involving CRP (23,33,37,39). The heterogeneity of the included studies was significantly high (I2=94%) in Tai Chi plus Drug treatment intervention.

The results show that Tai Chi was not associated with an effect on reducing CRP in Tai Chi intervention (SMD =–0.18, 95% CI: –0.61 to 0.25, P=0.41) (see Figure 6).

The results show that Tai Chi significantly reduced CRP in high exercise group (SMD =–1.98, 95% CI: –2.47 to –1.50, P<0.00001), but not in the low exercise group (SMD =–0.15, 95% CI: –0.47 to 0.16, P=0.33) (see Figure 7).

Due to the imbalance of the CRP at baseline (37), we adopted differences in changes from baseline to analyze (41).

Discussion

Based on the analysis of existing data, the effects of Tai Chi on CRP, TNF-alpha and IL-6 are related to the exercise amount. Our quantitative analysis demonstrated that Tai Chi significantly reduce TNF-alpha in all selected studies (36,38,40) and all of them were the high amount of exercise. Except for the subgroup analysis showed that Tai Chi with high exercise amount could reduce IL-6 and CRP but not with low exercise amount, Tai Chi was associated with decreased IL-6 (35,36) in Tai Chi plus Drug treatment intervention, and both interventions reached the standard of high exercise amount. Besides, the results showed that Tai Chi was not relevant in reducing CRP in Tai Chi intervention (33), and the exercise amount in this study was categorized as a low exercise amount.

In the clinical characteristics of COVID-19 patients, the average level of CRP is 23 mg/L (42), the average level of TNF-alpha and IL-6 is 8.3 ng/L and 34 ng/L respectively in moderate patients (43). Besides, the magnitude of the reduction of these inflammatory markers in Tai Chi are: TNF-alpha [40 (15.4%) to 36 (41%)]; IL-6 [33 (8%) to 36 (48.5%)]; CRP [33 (4.8%) to 37 (78.2%)]. According to these data, performing Tai Chi alone can hardly reduce the elevated inflammatory markers to the normal range. A previous study showed that Tai Chi had a better effect on reducing IL-6 in older adults with elevated IL-6 levels at baseline than the control group (33). Besides, another study also found that Tai Chi improved health function, especially in those who had the greatest impairments of health status at baseline (44). They are consistent with the actual situation of COVID-19 patients and provide evidence for Tai Chi as a complementary treatment for COVID-19 patients from another aspect.

Regarding the molecular mechanisms of Tai Chi’s effect on inflammatory markers, a previous systematic review (45) indicated that mind-body interventions (including Tai Chi) are related to downregulate the nuclear factor kappa B pathway, and it suggested that mind-body interventions may reduce the risk of inflammation-related diseases.

Besides, a previous meta-analysis (46) evaluated the effects of mind-body therapies on inflammatory markers, which revealed the effects of Tai Chi/Qi Gong on CRP and IL-6 could be ignored. However, this meta-analysis only included articles in the English language and was published 6 years ago with much literature updating during this period. Moreover, Tai Chi is different from Qigong (47), that study merged Tai Chi and Qi Gong to analyze the effects which may cause high heterogeneity. Our research focused on the effects of Tai Chi more accurately and comprehensively. Besides, a previous systematic review (48) indicated non-conventional interventions such as Tai Chi, have shown significant associations with IL-6 and TNF-α decreasing, which supports our conclusions.

On the feasibility of COVID-19 patients to perform Tai Chi, a study from China CDC (49) showed that the majority of COVID-19 patients (80.9%) were considered asymptomatic or mild infections. Among these patients, most of them can move freely. Besides, in Wuhan ’s first traditional Chinese medicine cabin hospital where Tai Chi was adopted as a complementary treatment, none of the patients turned into a severe case (http://www.satcm.gov.cn/xinxifabu/gedidongtai/2020-02-27/13444.html). Therefore, according to the specific conditions of the patients, it is feasible to perform Tai Chi for those who have the exercise ability with the guidance and assistance of professionals.

COVID-19 is caused by SARS-CoV-2, and the genome is similar to SARS-CoV which caused the outbreak of SARS in 2003 (50). A qualitative review (51) investigated five factors motivated SARS survivors in post‐SARS Hong Kong to practice Tai Chi, including deterioration of health caused by SARS-associated sequelae, unpleasant experiences during follow-up biomedical treatment, regaining an active role in recovery and rehabilitation, overcoming SARS-associated stigmas, preparing for potential stigmatization and discrimination during future epidemics. The study concluded that practicing Tai Chi helped the participants improve health and played a vital role in social function. The phenomenon refracted by the above motivations may also occur in patients with COVID-19. Thus, the practice of Tai Chi could be maintained for a long time in COVID-19 patients, even as a way of life.

Although this study found that Tai Chi has a certain role in reducing these inflammatory indicators, the evidence itself has limitations. The strength of evidence might be limited from the following reasons: (I) with a small sample size, resulting in low precision; (II) risk of bias of the original studies and relatively low methodological quality; (III) heterogeneity, from the PICO aspects; (IV) indirectness, that means the outcome indicators could not be a direct verification of the clinical practice.

For clinical heterogeneity, the original studies included in this study differ in patient groups. But they have increased inflammatory indicators in common and the effect of inflammation on diseases is the same. This meta-analysis explored the effect of Tai Chi on three inflammatory indicators, so merging different patient groups is feasible. The results of the heterogeneity test support it. Although meta-analysis didn’t include infectious disease patients, two controlled trials have assessed the effects of Tai Chi on clinically relevant immunity to varicella-zoster virus in the elderly and found Tai Chi can increase the specific cell-mediated immunity against the varicella-zoster virus (44,52). A previous review (53) also showed that Tai Chi could improve the immunity of the elderly population at risk of herpes zoster to varicella-zoster virus. It provided potential evidence for Tai Chi as a complementary treatment to COVID-19 patients indirectly.

Clinical researchers should consider several points in the future: (I) improving methodology quality of studies, including reporting the detail of allocation concealment and assessors blinding, and recording the number and reasons of missing data; (II) in order to reduce selective reporting, all clinical trials should be registered in advance on the international platform; (III) future research should pay more attention to the relationship between the exercise amount of Tai Chi and outcomes.

Cytokine storm is essential for the progression of COVID-19, which may cause serious complications and even death (54,55). The elevated levels of proinflammatory cytokines such as TNF-alpha and IL-6 are closely related to cytokine storm (56). Besides, CRP is a sensitive biomarker of inflammation and infection, which is induced by IL-6 in the liver (57). Based on the data from our study, we cautiously recommend Tai Chi as a complementary intervention to deal with COVID-19 patients and defer the coming of the cytokine storm.

Conclusions

The overall results elucidate that Tai Chi could significantly reduce TNF-alpha while it did not show the same effects in IL-6 and CRP. After subgroup analysis, Tai Chi with a high exercise amount can reduce IL-6 and CRP. This may further indicate that Tai Chi with a high exercise amount could be suggested as a complementary intervention for people with COVID-19.

Acknowledgments

Funding: This work was supported by National Natural Science Foundation (NO. 81973495), and the sponsor is the corresponding author.

Footnote

Reporting Checklist: The authors have completed the PRISMA reporting checklist. Available at https://dx.doi.org/10.21037/apm-21-640

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at https://dx.doi.org/10.21037/apm-21-640). The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- Wu C, Chen X, Cai Y, et al. Risk Factors Associated With Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome and Death in Patients With Coronavirus Disease 2019 Pneumonia in Wuhan, China. JAMA Intern Med 2020;180:934-43. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Remuzzi A, Remuzzi G. COVID-19 and Italy: what next? Lancet 2020;395:1225-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Sarzi-Puttini P, Giorgi V, Sirotti S, et al. COVID-19, cytokines and immunosuppression: what can we learn from severe acute respiratory syndrome? Clin Exp Rheumatol 2020;38:337-42. [PubMed]

- Yi Y, Lagniton PNP, Ye S, et al. COVID-19: what has been learned and to be learned about the novel coronavirus disease. Int J Biol Sci 2020;16:1753-66. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Liu K, Chen Y, Lin R, et al. Clinical features of COVID-19 in elderly patients: A comparison with young and middle-aged patients. J Infect 2020;80:e14-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Rothan HA, Byrareddy SN. The epidemiology and pathogenesis of coronavirus disease (COVID-19) outbreak. J Autoimmun 2020;109:102433 [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Pedersen SF, Ho YC. SARS-CoV-2: a storm is raging. J Clin Invest 2020;130:2202-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Chen G, Wu D, Guo W, et al. Clinical and immunologic features in severe and moderate Coronavirus Disease 2019. J Clin Invest 2020; [Crossref]

- Zhang C, Wu Z, Li JW, et al. Cytokine release syndrome in severe COVID-19: interleukin-6 receptor antagonist tocilizumab may be the key to reduce mortality. Int J Antimicrob Agents 2020;55:105954 [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wang L. C-reactive protein levels in the early stage of COVID-19. Med Mal Infect 2020;50:332-4. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ulhaq ZS, Soraya GV. Med Mal Infect 2020Interleukin-6 as a Potential Biomarker of COVID-19 Progression. Med Mal Infect 2020;50:382-3. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Dashti-Khavidaki S, Khalili H. Considerations for Statin Therapy in Patients with COVID-19. Pharmacotherapy 2020;40:484-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lee CCM, Thampi S, Lewin B, et al. Battling COVID-19: critical care and peri-operative healthcare resource management strategies in a tertiary academic medical centre in Singapore. Anaesthesia 2020;75:861-71. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Rodriguez-Morales AJ, Cardona-Ospina JA, Gutiérrez-Ocampo E, et al. Clinical, laboratory and imaging features of COVID-19: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Travel Med Infect Dis 2020;34:101623 [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bong CL, Brasher C, Chikumba E, et al. The COVID-19 Pandemic: Effects on Low- and Middle-Income Countries. Anesth Analg 2020;131:86-92. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Li F, Harmer P, Fitzgerald K, et al. Tai chi and postural stability in patients with Parkinson's disease. N Engl J Med 2012;366:511-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Scianni A. Tai Chi improves balance and prevents falls in people with Parkinson's disease. J Physiother 2015;61:44. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lü J, Huang L, Wu X, et al. Effect of Tai Ji Quan training on self-reported sleep quality in elderly Chinese women with knee osteoarthritis: a randomized controlled trail. Sleep Med 2017;33:70-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Tao J, Liu J, Liu W, et al. Tai Chi Chuan and Baduanjin Increase Grey Matter Volume in Older Adults: A Brain Imaging Study. J Alzheimers Dis 2017;60:389-400. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Polkey MI, Qiu ZH, Zhou L, et al. Tai Chi and Pulmonary Rehabilitation Compared for Treatment-Naive Patients With COPD: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Chest 2018;153:1116-24. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Zhu YQ, Peng N, Zhou M. Effect of Tai Ji Quan Training on Strength and Function of Lower Limbs in the Aged. Zhongguo Zhong Xi Yi Jie He Za Zhi 2016;36:49-53. [PubMed]

- Ma Ch HY, Shi Ch, Zhang W, et al. Effects of Practicing Tai Chi on Cardiac Function and 6-minute Walk Distance in Community Patientswith Coronary Heart Disease. Chinese Journal of Sports Medicine 2020;39:26-32.

- Lavretsky H, Alstein LL, Olmstead RE, et al. Complementary use of tai chi chih augments escitalopram treatment of geriatric depression: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 2011;19:839-50. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Yeung A, Lepoutre V, Wayne P, et al. Tai chi treatment for depression in Chinese Americans: a pilot study. Am J Phys Med Rehabil 2012;91:863-70. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Yeung AS, Feng R, Kim DJH, et al. A Pilot, Randomized Controlled Study of Tai Chi With Passive and Active Controls in the Treatment of Depressed Chinese Americans. J Clin Psychiatry 2017;78:e522-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Chew NWS, Lee GKH, Tan BYQ, et al. A multinational, multicentre study on the psychological outcomes and associated physical symptoms amongst healthcare workers during COVID-19 outbreak. Brain Behav Immun 2020;88:559-65. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Huang Y, Zhao N. Generalized anxiety disorder, depressive symptoms and sleep quality during COVID-19 outbreak in China: a web-based cross-sectional survey. Psychiatry Res 2020;288:112954 [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Janelsins MC, Davis PG, Wideman L, et al. Effects of Tai Chi Chuan on insulin and cytokine levels in a randomized controlled pilot study on breast cancer survivors. Clin Breast Cancer 2011;11:161-70. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Irwin MR, Olmstead R. Mitigating cellular inflammation in older adults: a randomized controlled trial of Tai Chi Chih. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 2012;20:764-72. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Campo RA, Light KC, O'Connor K, et al. Blood pressure, salivary cortisol, and inflammatory cytokine outcomes in senior female cancer survivors enrolled in a tai chi chih randomized controlled trial. J Cancer Surviv 2015;9:115-25. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Irwin MR, Olmstead R, Breen EC, et al. Cognitive behavioral therapy and tai chi reverse cellular and genomic markers of inflammation in late-life insomnia: a randomized controlled trial. Biol Psychiatry 2015;78:721-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Elkins MR, Moseley AM, Sherrington C, et al. Growth in the Physiotherapy Evidence Database (PEDro) and use of the PEDro scale. Br J Sports Med 2013;47:188-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Irwin MR, Olmstead R. Mitigating cellular inflammation in older adults: a randomized controlled trial of Tai Chi Chih. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 2012;20:764-72. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Janelsins MC, Davis PG, Wideman L, et al. Effects of Tai Chi Chuan on insulin and cytokine levels in a randomized controlled pilot study on breast cancer survivors. Clin Breast Cancer 2011;11:161-70. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wu F, Song EF, Bao Y, et al. Effect of type 24 simplified taijiquan on serum inflammatory cytokines and quality of life in type 2 diabetes patients. Chinese Journal of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation 2010;32:205-7.

- Li XB. Effects of Tai chi exercise on oxidative stress and inflammatory levels in elderly patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Chinese Journal of Gerontology 2013;33:5465-6.

- Li J, Chen Y, Xu J. Effect of Taijiquan Exercise on Elderly Patients with Stable Angina Pectoris. Medical Information 2018;31:75-7.

- Du ST, Ding LM, Yang FB, et al. The effects of Taijiquan on serum concentration of interleukin- 6, interleukin-8, tumor necrosis factor-α inpatients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in stationary stage. Chinese Journal of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation 2014;36:337-40.

- Chen D QM, Chen J. Observation on the Intervention Effect of Taiji Baihe Wings Brightening Technique on Ankylosing Spondylitis [Master]2014.

- Chen JX, Li YH, Wu YQ, et al. Effects of taijiquan exercise on depression and serum inflammatory factors in female college students. Chinese Journal of School Health 2019;40:1065-8.

- Higgins J, Green S. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions. Version 5.2.0. Cochrane Collaboration Website; 2017.

- Sun ML, Yang JM, Sun YP, et al. Inhibitors of RAS Might Be a Good Choice for the Therapy of COVID-19 Pneumonia. Zhonghua Jie He He Hu Xi Za Zhi 2020;43:E014 [PubMed]

- Chen L, Liu HG, Liu W, et al. Analysis of clinical features of 29 patients with 2019 novel coronavirus pneumonia. Zhonghua Jie He He Hu Xi Za Zhi 2020;43:E005 [PubMed]

- Irwin MR, Pike JL, Cole JC, et al. Effects of a behavioral intervention, Tai Chi Chih, on varicella-zoster virus specific immunity and health functioning in older adults. Psychosom Med 2003;65:824-30. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Buric I, Farias M, Jong J, et al. What Is the Molecular Signature of Mind-Body Interventions? A Systematic Review of Gene Expression Changes Induced by Meditation and Related Practices. Front Immunol 2017;8:670. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Morgan N, Irwin MR, Chung M, et al. The effects of mind-body therapies on the immune system: meta-analysis. PLoS One 2014;9:e100903 [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wang Tao XY. A Comparative Study of Similarities and Differences between Taijiquan and Qigong. Sports Science and Technology Literature Bulletin 2012;20:111-2.

- Moraes LJ, Miranda MB, Loures LF, et al. A systematic review of psychoneuroimmunology-based interventions. Psychol Health Med 2018;23:635-52. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Epidemiology Working Group for NCIP Epidemic Response, Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention. The epidemiological characteristics of an outbreak of 2019 novel coronavirus diseases (COVID-19) in China. Zhonghua Liu Xing Bing Xue Za Zhi 2020;41:145-51. [PubMed]

- Chan JF, Kok KH, Zhu Z, et al. Genomic characterization of the 2019 novel human-pathogenic coronavirus isolated from a patient with atypical pneumonia after visiting Wuhan. Emerg Microbes Infect 2020;9:221-36. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Siu JY. Coping with future epidemics: Tai chi practice as an overcoming strategy used by survivors of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) in post-SARS Hong Kong. Health Expect 2016;19:762-72. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Irwin MR, Olmstead R, Oxman MN. Augmenting immune responses to varicella zoster virus in older adults: a randomized, controlled trial of Tai Chi. J Am Geriatr Soc 2007;55:511-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Irwin M, Pike J, Oxman M. Shingles Immunity and Health Functioning in the Elderly: Tai Chi Chih as a Behavioral Treatment. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med 2004;1:223-32. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Mehta P, McAuley DF, Brown M, et al. COVID-19: consider cytokine storm syndromes and immunosuppression. Lancet 2020;395:1033-4. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Liu J, Li S, Liu J, et al. Longitudinal characteristics of lymphocyte responses and cytokine profiles in the peripheral blood of SARS-CoV-2 infected patients. EBioMedicine 2020;55:102763 [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Sun X, Wang T, Cai D, et al. Cytokine storm intervention in the early stages of COVID-19 pneumonia. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev 2020;53:38-42. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Heikkilä K, Ebrahim S, Lawlor DA. A systematic review of the association between circulating concentrations of C reactive protein and cancer. J Epidemiol Community Health 2007;61:824-33. [Crossref] [PubMed]